The constellation of Orion is one of the most familiar in the night skies. It is marked by a number of notable features, containing as it does three of the brighter stars in our night sky: Rigel: the 6th brightest star visible from Earth, and serving as Orion’s left foot; Betelgeuse, the 10th brightest, and serving as Orion’s right shoulder (so diagonally opposite Rigel); Bellatrix, the 26th brightest star in our sky, and sits at Orion’s left shoulder; and three galaxies – the Orion Nebula, the Messier 43 nebula, the Running Man Nebula – all of which can be found in Orion’s “sword”.

Orion – or more particularly – Betelgeuse – has been occupying a lot of the astronomy-related news cycles of late, with speculation that we might be witnessing the star’s potential move towards a cataclysmic supernova event.

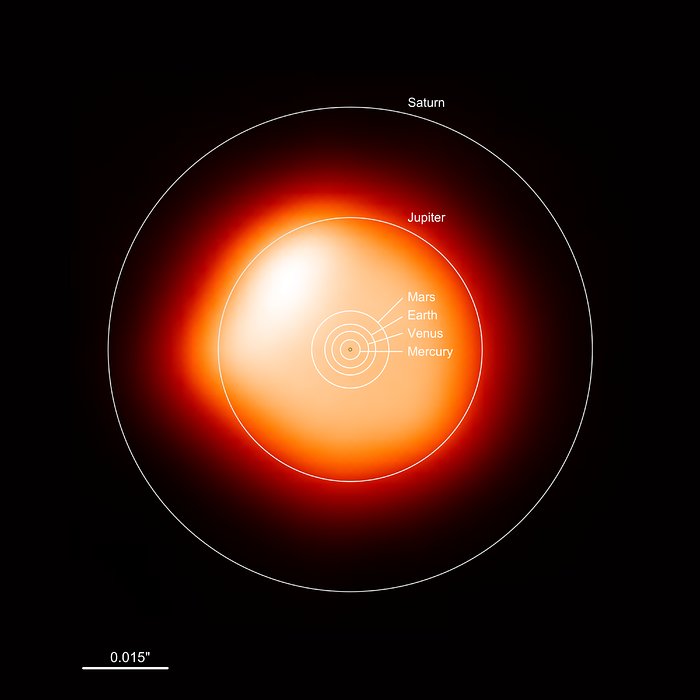

Before I get down to the nitty-gritty of why Betelgeuse has astronomers all a-twitter (quite literally, given the amount of Twitter chat on the subject), some details about the star. Classified a M1-2 red supergiant, Betelgeuse has a very distinctive orange-red colouration that can again be seen with the naked eye. However, it’s exact size is hard to determine, because it is both a semiregular variable star, meaning the brightens and dims on a semi-regular basis as it physically pulses in size, and because it is surrounded by a light emitting circumstellar envelope composed of matter it has ejected.

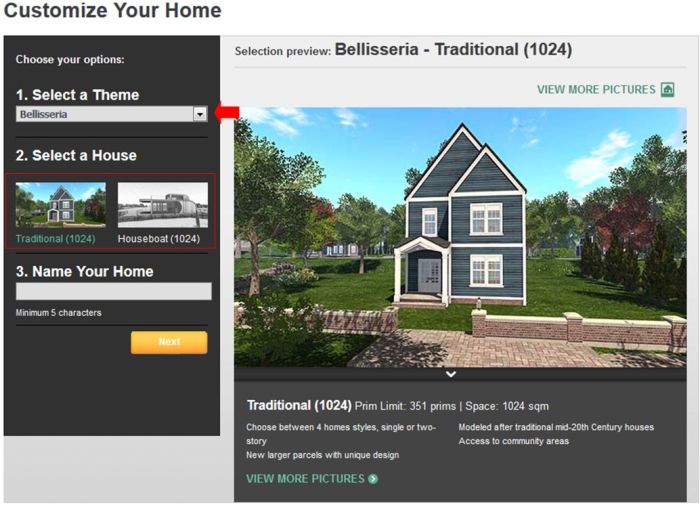

This means calculations over the years have given many different estimates of the star’s size, suggesting it is roughly 2.7 to 8.9 AU in diameter (1 AU = the average distance between the Earth and the Sun). This means that were the centre of Betelgeuse to be placed at the exact centre of the Sun, then its “surface” would be at least out amidst the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, or lie somewhere between Jupiter and Saturn!

That Betelgeuse is pulsating and has a cloud of material around it, also makes it difficult to pin down its precise distance from us. However, the most recent estimates suggest it is most likely around 643 light years from Earth, with a possible variation of around +/- 146 light years.

Red giant stars are of a type that have a comparatively short life, averaging 10-20 million years, depending on how fast they spin (compared to our Sun’s anticipated 9-10 billion years lifespan), with Betelgeuse thought to have a fast spin and an estimated age of about 8.5 million years, putting it close to its end of life, which tends to be a violent affair with stars of this size.

This is because these stars burn through their reserves of fuel at a high speed, although a temperature lower than typically found with Sun-type stars. Eventually, they reach a point where the temperatures generated by the nuclear process is insufficient to overcome the huge gravity created by their size, and they suddenly and violently collapse, compressing to a point where the pressure is so great, they explode outwards even more violently, tearing away most of their mass in an expanding cloud of hot gas called a nebula, leaving behind a tiny, dense core – or even a black hole.

However, while this final collapse and explosion takes place suddenly, the period leading up to it can be marked by observable changes in a star – and this is the reason for the excitement around Betelgeuse.

Over the last 20+ years Betelgeuse’s radius has shrunk by 15%. While this has not massively altered the star’s brightness over that time, it is still an astonishing amount of mass to lose over so short a period. More recently, however, there has been a further change in the star that has caused excitement: since mid-October 2019, Betelgeuse has gone through a stunning drop in its apparent magnitude – or brightness as seen from Earth’s location – dropping from being the 10th brightest object in our night sky to around the 27th, bringing with it a complete change in Orion’s appearance in our skies.

This sudden drop in brightness has been seen by some as a possible indicator that Betelgeuse may have gone supernova, and we’re now waiting for the light of the actual explosion to reach us. Such has been the interest, reference has been made to monitoring neutrino detectors for the first signs of an explosion. This is because whereas photons have to escape a star’s collapse, neutrinos don’t, and so will reach us ahead of any visible light; so a sudden increase in the number of them detected coming from the region of the sky occupied by Betelgeuse could be indicative of it having exploded.