July 20th marked two anniversaries, the first manned landing on the Moon (July 20th, 1969) by Apollo 11, and the first American automated soft-landing on Mars with Viking Lander 1 (July 20th, 1976). As such, I’m starting this Space Sunday with a short look at both events.

Apollo Lunar Module (LEM) Eagle arrived on the surface of the Moon at 20:18:04 UTC on July 20th, 1969 after being launched atop a Saturn V rocket along with Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin from the Kennedy Space Centre Launch Complex 39A at 13:32:00 UTC on July 16th, 1969. It was the culmination of John F. Kennedy’s vision to re-assert America’s industrial and technological leadership in the world.

The land was dramatic in every sense of the word. On separation from the Command Module, the LEM immediately experienced issues communicating directly with Earth, then there were the infamous 1202 master alarm which triggered the LEM’s landing computer to re-boot itself, followed by a 1201 alarm. Then there was the discovery that, fair from being smooth and flat, the main landing site was boulder strewn, forcing Armstrong to fly the LEM to the limits of its available descent fuel in order to find a suitable landing area.

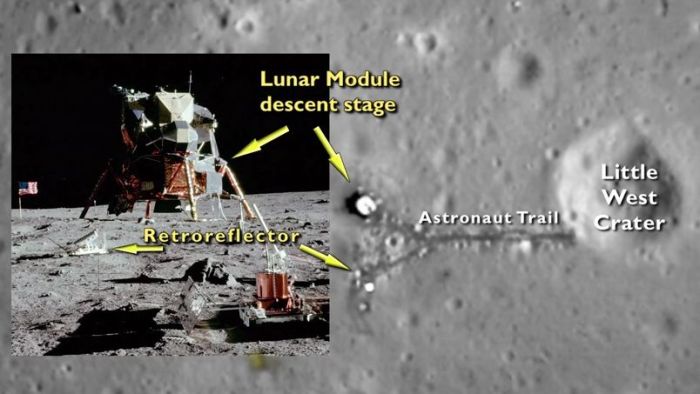

Armstrong finally set foot on the Moon on July 21st at 02:56:15 UTC, after he and Aldrin (the LEM Pilot) had been given the opportunity to rest. Aldrin followed Armstrong down the ladder 20 minutes later, and together they spent about 2.5 hours on the surface, collecting 21.5 kg (47.5 lbs) of lunar material for return to Earth. Their total time on the Moon was short – just under 22 hours – but Aldrin and Armstrong between them, seen in fuzzy black-and-white television footage and (later) crisp photos, forever changed humanity’s perception of the Moon and its place in the cosmos.

To Mark the 47th anniversary of the landing, which also saw Collins remain in orbit piloting the Command and Service Module (CSM), The National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC has produced a 3D tour (with other goodies) of the Apollo Command Module Columbia, as seen from the pilot’s (Collin’s) seat. This can be run in most browsers and offers a first-hand tour of the vehicle.

For those who prefer a visual record, NASA issued a restored film of the entire Apollo 11 EVA on YouTube in 2014. Or you can re-live the entire mission in just 100 seconds, courtesy of Spacecraft Films, which I’ve embedded below.

Apollo 11 was the first of six missions to the Moon (Apollo 13 being famously aborted after a critical failure within the Service Module whilst en route to the Moon), which concluded on December 19th, 1972, when Apollo 17 splashed down in the South Pacific Ocean, the only Apollo mission to fly a fully qualified geologist to the Moon (Harrison Schmitt).

In the 44 years since the end of the Apollo lunar project, human spaceflight has been confined to low-Earth orbit and will not move beyond it until the 2020s (with the uncrewed Exploration Mission 1 serving as the preliminary flight for that move in 2018). As such, it is all too easy to dwell on the political motivations which led to the programme, rather than on the phenomenal achievement Apollo actually was. Today’s plans for moving beyond LEO once more, and for sending Humans to Mars, may seem long overdue but they nevertheless build on the foundations laid down by Apollo.

Viking Lander 1 arrived on the surface of Mars seven years to the date after Apollo 11 arrived on the Moon – although that hadn’t been the original intent. 1976 saw the United States celebrating its bicentennial, and it had originally been intended that the Lander would touch-down on the Red Planet on July 4th of that year.

However, after arriving in orbit on June 19th, 1976, the Viking orbiter craft used its imagining systems to survey the proposed landing site, which had been “scouted” from orbit by the Mariner 9 mission – the first vehicle to orbit Mars – in 1971 / 72. Unfortunately, the Viking orbiter’s much more capable cameras revealed the primary landing site to be far rougher than had been believed, leading to a decision not to land there, but to survey the back-up sites prior to committing to a landing on July 20th, and thus to instead celebrate Apollo 11’s triumph instead of America’s Independence Day.

Given the state of play of planetary exploration at the time, Viking was a massively impressive mission: two orbiter vehicles launched back-to-back, carrying two lander vehicles in turn carrying an impressive set of 5 experiments intended to seek signs of life on Mars. At the time, no-one actually knew the density of the Martian upper atmosphere or the load-bearing strength of the Martian surface or what they might actually find on the surface. There were genuine fears that the latter might be all dust, and the lander could simply dig itself a hole when firing its retro-rockets at the final point of landing and then fall into it, or if it did arrive safely, whether it might sink into the Martian dust; hence why the first image to be returned by the lander following touchdown prominently featured one of its own landing pads (above).

Continue reading “Space Sunday: looking back, looking forward, looking inside”