Shenzhou-12, China’s first crewed mission to orbit in almost 5 years, lifted-off from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in northwest China at 01:22 UTC on the morning of Thursday, June 17th, heading towards the Tianhe core module of the country’s new space station.

Carried aloft by a Long March 2F booster, the mission comprises three taikonauts Nie Haisheng (mission commander) and Liu Boming, both of whom have previously flown in space, and rookie Tang Hongbo. Together, they will spend three months at the space station, putting it through a series of commissioning tests and operations.

Following launch, the Shenzhou vehicle performed a rapid chase-and-catch with the Tianhe module, docking with it some 6 hours 32 minutes later. In doing so, it became the second vehicle to dock with the module, the first being the Tianzhou-2 resupply vehicle which delivered essential supplies and equipment to the fledgling space station at the end of May 2021.

Overall, Shenzhou-12 is the the third of eleven flights China has planned between now and the end of 2022 in order to complete the Tinagong station, the first having been the Tinahe module itself. These launches will include two science modules and additional Shenzhou crew and Tianzhou resupply missions.

The flight of Shenzhou-12 also marked the first time China has used the chase-and-catch approach to orbital rendezvous. It is a technique both Russia and the United States have started to employ in order to more quickly deliver cosmonauts and astronauts to the International Space Station; for China, it meant reducing a typical two-day rendezvous time seen with the earlier Tiangong orbital laboratories to just the 6+ hours seen in this flight.

Prior to launch, the crew were treated to a parade and celebration by members of the People’s Liberation Army and their families (there is no real civil / military distinction in China’s human spaceflight operations), whilst their arrival and boarding the Tinahe marked the first time since May 2000 that two orbiting space stations have been simultaneously inhabited – back then it was the ISS and Russia’s soon-to-be-decommissioned Mir. Now it is the ISS and the nascent Tiangong station.

Ahead of the launch and during an international conference on space development, China joined with Russia in formally announcing the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), intended to serve as ” a comprehensive scientific experiment base built on the lunar surface and on [sic] the lunar orbit”, inviting international partners to join them.

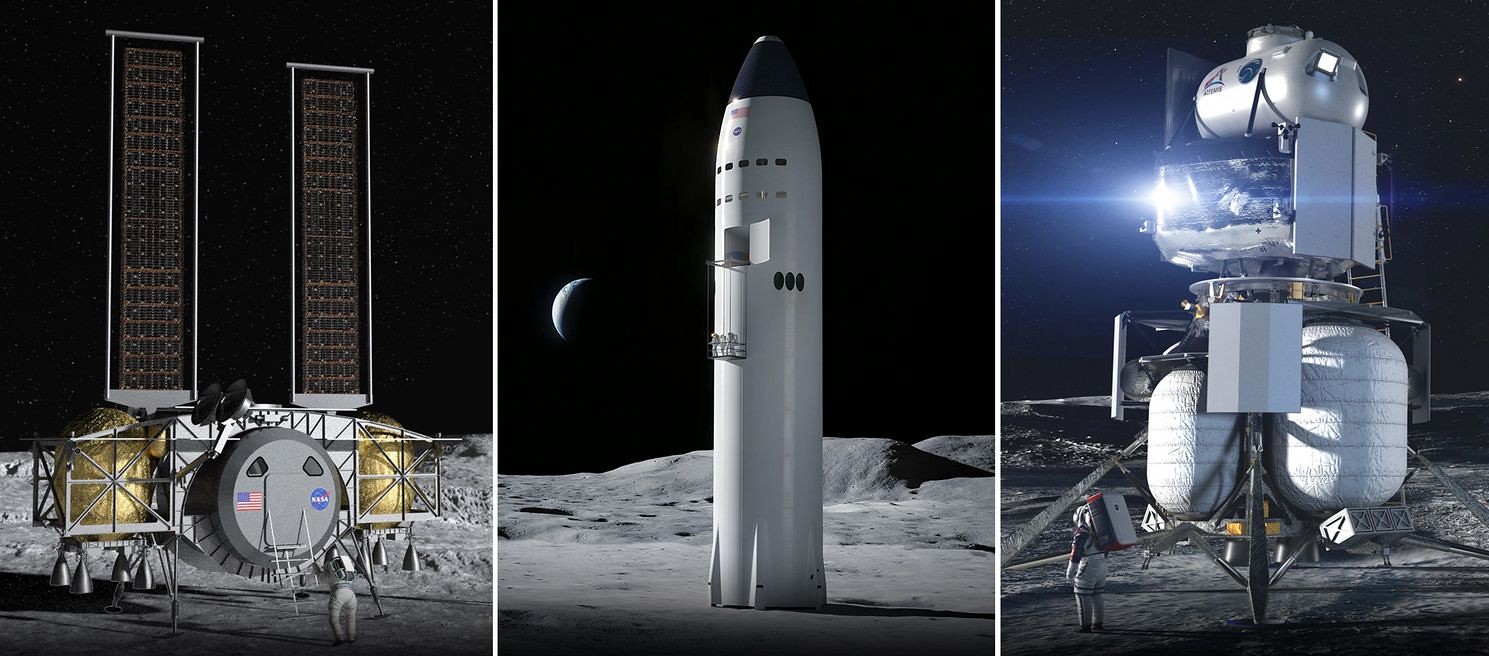

ILRS is seen as something of a competitor to the American-led Artemis programme, and during the presentation representatives of Russia’s Roscosmos and the China National Space Administration (CNSA) indicated that ILRS will (like Artemis) combine a Moon-orbiting space station with a surface base in the lunar south polar region.

First announced in March 2021, after Russia rejected US overtures to be a part of Artemis, the ILRS looks set to undergo a rapid cycle of development. China and Russia anticipate working together between 2021 and 2025 to select the preferred location for the lunar base, with actual deployment and construction to commence in 2026 and continue through until 2036. During the construction phase, the two countries plan to place a station into cislunar space which will act as a waystation between their orbital facilities in Earth orbit and the lunar base (China will use their Tiangong station at the “earth end” for flights to / from the Moon, and Russia will use its recently-announced new space station, which it intends to have operational by 2030).

According to both countries, the focus of ILRS will be to “carry out multi-disciplinary and multi-objective scientific research activities including exploration and utilisation, and lunar-based observation.” They further indicated that the European Space Agency (ESA), Thailand, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have all declared an interest in joining the project.

And if that weren’t enough, China has also announced it intends to develop the means to establish a long-term / permanent human presence on Mars.

Speaking at the same event at which the ILRS was officially confirmed, Wang Xiaojing, president of the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT), unveiled an ambitious programme that would see China extend is robotic exploration of Mars before moving to more extended automated missions using chemical rockets to deliver ISRU (in-situ resource utilisation) missions for the production of air, water and fuel through locally-available resources. From there, Wan indicated the country would start delivering payload missions to Mars aimed at supporting a human presence.

For actual crewed missions, Wan said China would use nuclear-powered “ferries” operating between Earth and Mars, dramatically reducing flight times. Built in Earth orbit, these would eventually become “cyclers”, with two or possibly three craft looping between the two planets, with crews and their equipment launching from Earth to join one for the trip to Mars, and then at the end of their mission hitching a ride home on another of the ferries as it swings around Mars.

No time frames for when all this might happen were given, and China has a huge mountain to climb in terms of technology development – ISRU system, life support systems, operating human missions in deep space (and with suitable solar / cosmic radiation protection). It also has to develop the planned nuclear thermal engines the “ferries” would use and gain experience in operating them and ensuring they don’t add radiation exposure risks to crews . All of this, coupled with the ILRS plans, likely means China will not be in a position to undertake any kind of human mission to Mars before the 2040s, even if Wan’s presentation turns into a programme.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: China’s ambitions, telescopes and SLS”