Elon Musk has announced the first payload that will be flown aboard the SpaceX Falcon Heavy, together with an ambitious goal in mind.

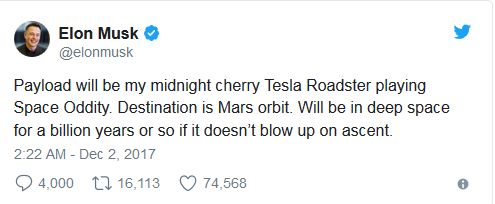

The maiden flight of the new heavy lift launcher had been expected to take place in December, as a part of an ambitious end-of-year five launch schedule. However, in tweets on Friday December 1st, 2017, Musk indicated the Falcon Heavy flight will now take place in January 2018. When it does, and if all goes according to plan, be sending Musk’s own car on its way to Mars – and possibly beyond.

A car might sound a weird payload, but it is entirely in keeping with SpaceX’s tradition; the first Dragon capsule test flight in 2010 carried a giant wheel of cheese into space.

The first tweet on the launch also underlines Musk’s own uncertainty about its potential success; he has previously stated that he expects the first flight of the Falcon Heavy may end in a loss of the entire vehicle, simply because of the complexities of the system.

Comprising three Falcon 9 first stages strapped together side-by-side and firing 27 main engine simultaneously at launch means the vehicle will be generating a tremendous amount of thrust requiring all three stages to work smoothly together. They’ll also be generating a lot of vibration during the rocket’s ascent through the denser part of the Earth’s atmosphere. Only so much of this can be simulated and modelled; a maiden flight is the only way to find out where the remaining issues might lie.

However, if the launch is successful, it will be spectacular, involving the recovery of all three Falcon 9 stages to safe landings back on Earth. It will also boost Musk’s car towards Mars – which raises a question. Does SpaceX aim to orbit the car around Mars, or will the mission simply be a fly-by?

Any attempt to achieve Mars orbit would require some kind of propulsion system to perform an orbital insertion burn, something which adds complexity to the mission. However, given Musk’s ambitions with Mars, placing even such an unusual payload into Mars orbit could yield valuable data for SpaceX. The car weighs 1.3 tonnes, so the total mass launched to Mars – car (likely modified somewhat, although the stereo will – according to Musk – be playing David Bowie’s Space Oddity during the ascent) payload bus, propulsion system, fuel, some kind of science system (why orbit Mars only to pass up the opportunity to gather data?) – could amount to around double that, if not more.

Musk’s comment about the payload being in “deep space for a billion years” seems to suggest the mission might by a fly-by, sending the car onwards and out across the solar system and beyond. Again, with a science payload sharing the space with the car, this could generate useful data. Either way the launch of such an unusual payload is likely to require additional US Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) approval; it will certainly require a launch license – which the FAA has yet to grant.

NASA Turns to Lunar Rover to Help With Next Mars Rover Mission

I’ve followed the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission, more generally referred to as the Curiosity rover mission since 2012, tracking the discoveries made and the ups and downs of the mission. Overall, the rover has carried out some remarkable science and made a range of significant discoveries concerning ancient conditions within Gale Crater on Mars and the overall potential for the planet to have been able to potentially support microbial life at some point in its history.

But there have been hiccups along the way – computer glitches, issues with some of the rover’s hardware, and so on. These included was the 2013 discovery that Curiosity’s wheels were starting to show clear signs of wear and tear less than a year into the mission. The discovery was made during a routine examination of the rover’s general condition, carried out remotely using the imaging system mounted on Curiosity’s robot arm.

The images captured of the rovers six aluminium wheels, each some 50 cm (20 inches) in diameter, revealed tears and a number of jagged punctures in one of them (above), the result of passage over the unforgiving, uneven and rock-strewn surface of Mars. While damage was not – and has not – become severe enough to threaten Curiosity’s ability to drive, at the time they were found, it did cause mission planners to revise part of the rover’s mission as it drove along the base of “Mount Sharp” near the centre of the crater, in order to avoid traversing a region shown from orbit to be particularly rugged. Since then, care has been taken to avoid exposing the rover to particularly rough areas of terrain.