In 2005, along with friends, I attended a dinner at which a UK scientist, John Zarnecki, was honoured. His name might not be familiar to some, but Professor Zarnecki, currently serving as the Director of the International Space Science Institute in Berne, Switzerland, has been involved in a number of high-profile space missions, including the Hubble Space Telescope, the Giotto probe that visited Halley’s Comet, and UK’s Beagle 2 mission to Mars. He is currently leading the European ExoMars rover mission, scheduled for 2020.

However, it is probably with the NASA / ESA Cassini-Huygens mission that he has the deepest association. At the time of the dinner, Professor Zarnecki had already been involved in that programme for fifteen years. His primary responsibility was the Huygens probe, which became the first vehicle to land there in January, 2005, and still holds the record for the furthest landing from Earth a spacecraft has so far made.

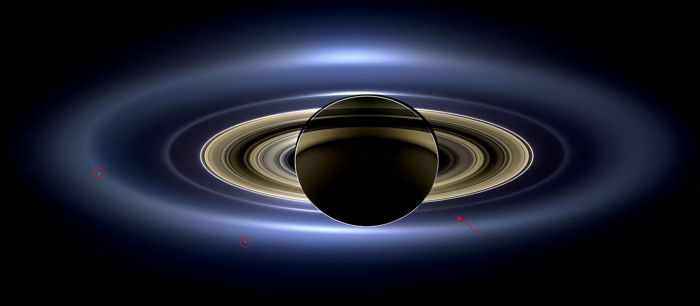

I mention this, because while the Titan surface mission effectively came to an end 90 minutes after the lander arrived there, the Cassini vehicle has remained in operation around Saturn and its moons, gathering a huge amount of data in the process. However, its own mission is now coming to an end after almost 20 years. In September 2017, Cassini will complete its last full orbit of Saturn and then fall to is destruction.

Before then, however, and starting on November 30th, 2016, the orbiter will commence the penultimate phase of its mission. Having gradually shifted itself into a more polar orbit around Saturn Cassini will commence a series of “ring-grazing orbits”, coming to within 7,800 km (4,850 mi) of what is regarded as the outer edge of Saturn’s major series of rings, the F-ring.

These orbits, which will extend through April 22nd, 2017, will see the spacecraft dive through the more diffuse G-ring once every seven days for a total of 20 times in what will be the first attempt to directly sample the icy particles and gas molecules which are located at the edge of the rings and also image the tiny moons of Atlas, Pan, Daphnis and Pandora, which play a role in “shepherding” the rings around Saturn.

Over time it will slowly close on the outer edge of the denser F-ring, until in March and April 2017, it is passing through the outer reaches of that ring, some 140,180km (87,612.5 mi) from the centre of Saturn. The F-ring is regarded as perhaps the most active ring in the Solar System, with features changing on a timescale of hours.

Exactly how the majority of Saturn’s rings formed is still unknown;, with ideas focused on one of two theories. In the first, the material in the rings is the original material “left over” from the formation of Saturn and its larger moons, pulled into a disc around the planet by gravitational tides. In the second, the material is all that remains of a form er – called Veritas after the Roman goddess – which either crossed the Roche limit to be pulled apart by gravitation forces or was destroyed by the impact with another body such as a large comet or asteroid.

However, in both of these cases it is not unreasonable to assume that the material making up the rings would be of a mixed nature: dust, ices, rocky matter, etc. However the majority of the ring matter is icy particles, with little else. This has given rise to a variation on the destroyed moon theory: that the particles are all that remains of the icy mantle of a much larger, Titan-sized moon, stripped away as it spiralled into Saturn during the planet’s formation.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: ring grazing and exoplanet gazing”