Sunday, October 27th, 2019 saw the return to Earth of one of the US Air Force X-37B “mini-shuttles” after a record-breaking 780 days in space.

The uncrewed vehicle, originally developed by NASA, has been operated by the USAF since it took over the programme in 2004, undertaking the first drop-tests of the vehicle in 2006. Since starting orbital missions in 2010, the vehicle has been subject to much speculation and conspiracy theories, largely because most of its orbital operations have been classified, with only a few details of experiments carried being offered to the public.

Officially designated Orbital Test Vehicle (OTV), there are two X-37B vehicles known to be in operation, although it is not clear which vehicle returned to Earth on October 27th, 2019 at 03:51 EST – while the USAF has previously noted the vehicle engaged in a mission as either OTV 1 or OTV 2, they remained silent on the vehicle involved in this 5th mission both prior to its September 7th, 2017 launch atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 booster, and throughout the mission, although it is believed that based on the mission count to date, it was most likely OTV 1.

As with previous missions, the majority of the vehicle’s payload has been classified, with the USAF only confirming one experiment carried was the Advanced Structurally Embedded Thermal Spreader II (ASETS-II), a system for dispersing heat build-up across flat surfaces such as electronic systems such as CPUs and GPUs through to the likes of spacecraft surfaces.

Elsewhere, the USAF has indicated that OTV will be used to test advanced guidance, navigation and control systems, experimental thermal protection systems, advanced avionics and propulsion systems and lightweight electromechanical flight systems. Some of these have been witnessed through all five of OTV’s missions to date – notably the vehicle’s guidance, navigation, control and flight systems. It is some of these uses that have led to the speculation around the vehicle’s intended purpose.

This latest mission, for example, saw an OTV inserted into a higher inclination orbit than previous missions. This both expanded its operational envelope and allowed the vehicle to modify its orbit during flight. Both of these aspects of the mission caused some to again point to the idea that that OTV is intended to be some form of weapons platform (highly unlikely when one considers the complexity of orbital mechanics), to the the idea that it is some kind of super-secret spyplane (again unlikely, given that the US operates a network of highly-capable “spy” satellites).

Even when it comes to the tasks OTV is designed to perform, fact is liable to be more mundane than conspiracy theory would like. For example, while OTV has been used to test a new propulsion system, it is not some super-secret (and mythical) EM drive NASA has supposedly developed, but rather a Hall effect ion drive thruster.

OTV-5 / USA-277 not only achieved the longest duration flight of the programme to date, it marked the first time an X-37B was launched from Kennedy Space Centre and return to KSC – all the previous flights had been been launched from either Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida (adjacent to KSC) or Vandenberg, California, Air Force Base, although the previous mission, OTV-4 / USA-212 was the first to land at KSC’s Shuttle Landing Facility (the first 3 missions all landing at Vandenberg AFB). Overall, the 780 day mission brings the total time the X-37B vehicles have spent in space over 5 missions to an astonishing 2,865 days, or (approx) 7 years and 10 months, in orbit – more than double the total amount of time (1,323 NASA’s entire shuttle fleet spend in orbit over 30 years of operations.

The next flight for the system is expected to launch in the first half 2020.

Pluto’s Far Side Revealed

In July of 2015, NASA’s New Horizons vehicle, the core part of a mission of the same name, shot through the Pluto – Charon system, making its closest approach to the dwarf planet and its (by comparison) oversized moon on July 14th of that year. Launched in 2006 the mission spent a relatively brief amount of time in close proximity to Pluto as it shot through the system at 50,700 km/h (31,500 mph), but it has completely turned our understanding of this tiny, cold world completely on its head – as I’ve hopefully shown in writing about Pluto and the mission in these pages.

So much data was gathered during the fly-by that it took months for the probe to return it all to Earth, and even now, four years after the encounter, that data is still being sifted through and researched. Within the data were many, many splendid high-resolutions of the “encounter side” of Pluto – the sunward-facing side of the planet the spacecraft could clearly image as it sped into closest approach – many of which have again appeared in these pages as well as elsewhere.

However, the joy at the amount of information the mission returned has been mixed with a degree of frustration. The nature of the fly-by means that while New Horizons gathered spectacular images of the “encounter side” of Pluto, by the time sunlight was falling across what had been the “far side” of the dwarf planet during closest approach, the probe was so far away it could not capture images to the same level of resolution as gained with the “encounter side”.

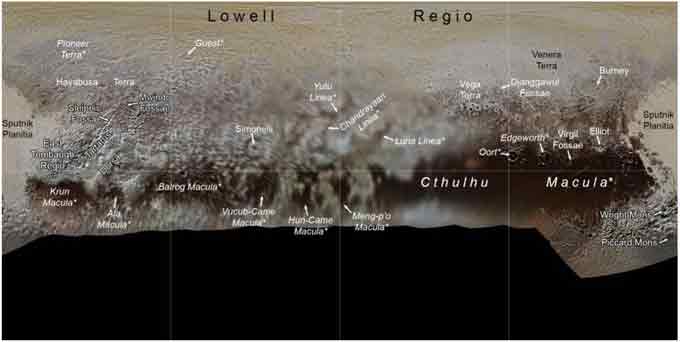

But now a new study has sought to try to balance things out and offer an integrated look at Pluto’s far side in an attempt to understand the planet as a whole. The study uses data gathered from across all of New Horizons’ science suite and attempts to bring it all together into a cohesive whole, and it reveals that Pluto’s far side is both very different to the “encounter side” – and also very similar in places.

The similarity comes in the form of what have been called “bladed terrains”. These were first noted on the encounter side’s eastern regions, and also appear in images New Horizons was eventually able to return of Pluto’s “far side”. They are thought to be vertical shards of methane ice up to 300 m (1000 ft) high. They are thought to be similar in nature to penitente features found in the Chilean Andes, and the result of sublimation, except that where Pluto’s features are massive and methane dominated, those on Earth are rarely taller than 5 m (16 ft) and are the result of sublimation of snow.

One of the striking differences between the planet’s two hemispheres is the extreme icy smoothness of Sputnik Planitia on Pluto’s “encounter side” and an extremely chaotic region sitting exactly opposite it on the planet’s surface, marked by strange blotches and intersecting lines. The most likely explanation for this latter terrain is that Sputnik Planitia is s deep depression resulting from a massive impact that sent shock wave rolling around the planet, which came together on the other side. In this, Mercury has two similar notable features: the Caloris Basin, one of the largest impact craters in the Solar System, and directly opposite it, a chaotic regions simply dubbed Mercury’s “weird terrain”.

There’s a lot more to be determined about Pluto’s far side and the planet as a whole, but the Far Side Project has started to unlock more of Pluto’s secrets, and it is hoped that the upcoming generation of Earth-based telescopes such as the 30 Metre Telescope and the Giant Magellan Telescope will be able to reveal more information about Pluto and Charon.

InSight’s Mole Reverses Course

Mars, it seems, is full of surprises.

In my previous Space Sunday update I noted that there had been some success in getting the “mole” – a key part of the HP³ experiment – moving again after it had become stuck for the better part of 2019 whilst trying to burrow into the surface of Mars.

The self-propelled probe had become stuck when it could not obtain sufficient traction to continue its downward motion, eventually prompting the mission team to use the InSight lander’s robot arm to push it against the exposed part in the hope that would give it sufficient traction against the side of the hole to resume its downward motion.

The attempt appeared to work, as I noted in that previous report: after tests, the “mole” was able to resume pushing its way down into the Martian regolith. However, the weekend of October 26/27th saw things take an odd turn – as NASA confirmed while this column was being written – the probe actually reversed course and managed to raise itself half-way back out of its hole.

Precisely how it did this is unclear: the “mole” uses a percussive action and frictional contact with the sides of hole it makes to drive itself into the ground. Essentially an electric motor that contracts a spring, “winding in” a weight at the head of the probe. When released, the spring powers the weight forward, driving the pointed hammer into the ground, pulling the rest of the probe behind it, the walls of the hole and the length of the probe absorbing the “rebound”.

When it got stuck, one theory was that the probe was unable to gain the required traction against the hole walls due to the properties of the material it was moving through – leaving it “bouncing” on the spot each time the spring was released. It’s now thought that the material is so loose, some of it is somehow collapsing into the hole as the probe “bounces”, causing it to jump backwards when the spring releases, causing more of the hole to collapse under it so the next time the spring releases, it again jumps backwards, releasing more material to fill the hole.

Until such time as what is going on can be reasonably determined, operations with the “mole” have again been halted.

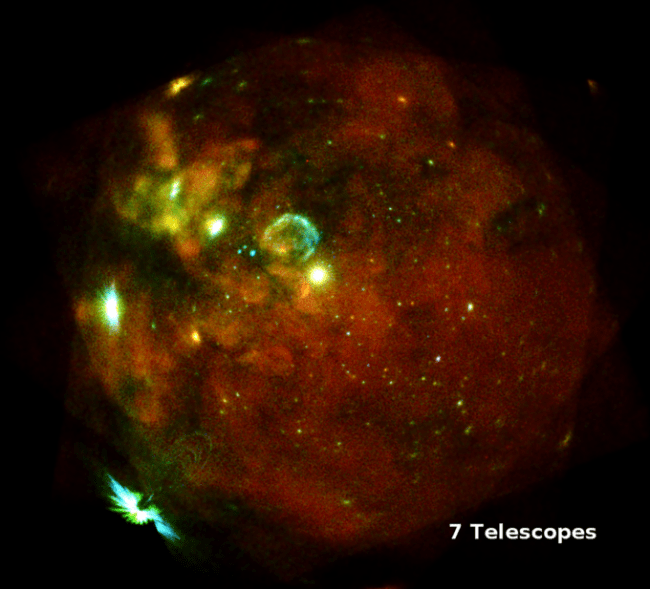

Space Picture of the Week

In July 2019, Russia launched the Russian-German Spektr-RG space observatory, which has carries a number of instruments that have been undergoing commissioning / calibration. One of the instruments on the platform is eROSITA is an X-ray instrument built by the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) in Germany, designed image the entire sky in the X-ray band over a 7-year period in the hunt for signs of dark energy.

As a part of its commissioning and calibration, eROSITA took a series of images using all seven of its mirror instruments (think of them as 7 telescopes in one instrument), some of which were combined to perform the most remarkable image of the Large Magellanic Cloud, our galactic neighbour, yet captured.