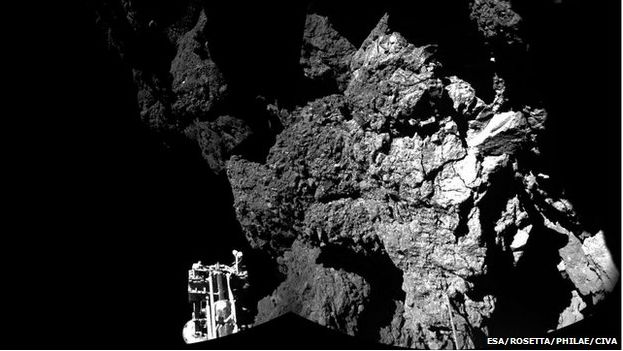

On Wednesday, November 12th, after 10 years in space, travelling aboard its parent vehicle, Rosetta, the lander Philae touched down on the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko (67P/C-G). It was the climax of an amazing space mission spanning two decades – and yet was to be just the beginning. Packed with instruments, it was hoped that Philae would immediately commence around 60 hours of intense scientific investigation, prior to its batteries discharging, causing it to switch to a solar-powered battery system.

Unfortunately, things didn’t quite work out that way. As I’ve previously reported, the is very little in the way of gravity on the comet, so in order for Philae to avoid bouncing off of it when landing, several things had to happen the moment it touched the comet’s surface. As it turned out, two of these things didn’t happen, with the result that the lander did bounce – twice.

The first time it rose to around 1 kilometre above the comet before descending once more in a bounce lasting and hour and fifty minutes, the second time it bounced for just seven minutes. Even so, both of these bounces meant the lander eventually came to rest about a kilometre away from its intended landing zone. What’s worse, rather than touching down in an area where it would received around 6-7 hours of sunlight a “day” as the comet tumbles through space, it arrived in an area where it was only receiving around 80-90 minutes of sunlight – meaning that it would be almost impossible to charge the solar-powered battery system.

Even so, the lander commenced science operations as planned, and despite having only limited power within its batteries, and insufficient means to fully recharge them, Philae returned almost all of its anticipated science data. However, in the morning of Saturday, November 15th (UK / European time), being unable to charge its solar batteries, the lander “safed” itself and entered a state of hibernation, leaving scientists hoping that as the comet continues towards the Sun, sufficient sunlight would fall across the lander in order for it to successfully recharge its batteries.

It happened. On Sunday, June 14th, ESA operations announced that communications with Philae had been re-established.

So far, some 300 packets of data have been returned to Earth via Philae’s parent craft, Rosetta, as it orbits the comet since communications were re-established at 23:28 GMT on Saturday, June 13th. This data revealed that Philae appears to have been awake for a while, the comet’s “fall” towards the Sun having done the trick, but the Sunday, June 14th contact marked the first time Philae had managed to reach Rosetta.

The initial 85-second communication is still being analysed, but has indicated there are around 8,000 additional packets of data to be returned by the lander, the initial information being largely concerned with information on Philae’s overall condition.

As well as tweeting directly on the resumption of contact, ESA also issued a Tweet “from” Philae announcing the news.

That there is still some 8,000 packets of data still within Philae’s memory, which is likely to be science data the lander has gathered over the last few days as it has come out of its seven month hibernation. As the comet becomes more active as it continues inward towards the sun-ward, Philae is in a prime position to discover more about these remnants of the earliest history of the solar system.

During its initial 60 hours of operations prior to going into hibernation, The lander discovered organic molecules on the comet, results of which were sent back from Philae’s Cosac instrument (one of the ten science instruments on the lander), thus fulfilling one of its primary mission objectives.

While Philae may have been in hibernation for the last seven months, its parent vehicle, which bears the same name as the mission, has not and has continued to orbit the comet and gather data as the comet gradually sweeps through the solar system towards the sun – it is currently some 205 million kilometres (127 million miles) distant, and will reach its nearest point in August before heading back in to the far reaches of the solar system.

One of the more interesting discoveries made by the mission is that the water vapour from comet 67P is substantially different from that found on Earth, having three times the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen when compared to terrestrial water. This makes it very unlikely that water found on Earth came from comets such as comet 67P, one of the common hypotheses for liquid water on Earth being that it resulted from a very young Earth being repeatedly bombarded by asteroid and cometary fragments rich in water.

The Rosetta mission actually started 21 years ago, in 1993 when it was approved as the European Space Agency’s first long-term science programme. The aim of the mission being to reach back in time to the very foundations of the solar system by rendezvousing with, and landing on, a comet as it travels through the solar system. Now, with Philae once more operational, it would seem that all of the science aims for the mission can be completed – including obtaining and analysing samples of the comet itself, using the compact hammer and drill systems aboard the little lander.

Due to Rosetta’s complex orbit around the comet, combined with the way in which the comet itself in tumbling through space, it will be another few days before contact with Philae is resumed. However, the science team is confident that now the lander has woken up, maintaining contact won’t be a problem – at least until the comet becomes very active as a result of its close approach to the Sun.

“Philae is doing very well: It has an operating temperature of -35ºC and has 24 Watts available,” said Philae’s Project Manager Dr Stephan Ulamec. “The lander is ready for operations.”