In my last Space Sunday update, I was writing at the very time a final effort was being made to see a little Japanese space probe finally achieve an operational orbit around Venus, precisely five years to the date after the first attempt failed as a result of the craft’s primary motor malfunctioning.

At the time of writing that update, it appeared as if little Akatsuki (“Dawn”), designed to probe the Venusian climate and atmosphere had finally arrived in orbit about the planet, but as I noted, final confirmation would take a while. In the end, it wasn’t until Wednesday, December 9th that the Japan Aerospace eXploration Agency (JAXA) did confirm Akatsuki, less than a metre on a side (excluding its solar panels) was secure in its orbit around Venus and would likely be able to complete its mission.

Following the failure of its main engine on December 7th 2010 during a critical braking manoeuvre, the probe had finished up in a heliocentric orbit, circling the sun and heading away from Venus. However, orbital mechanics being as they are, both the probe and Venus would occupy the same part of space once again in December 2015, presenting final opportunity to push the probe into orbit using its RCS manoeuvring thrusters. This is precisely what happened on the night of December 6th / 7th, 2015. While not designed for this purpose, a set of the probe’s RCS thrusters undertook a 20-minute burn just before midnight UTC on December 6th, and preliminary telemetry received on Earth some 30+ minutes later showed Akatsuki had achieved sufficient braking to enter a very elliptical orbit around Venus.

Data received since then show that the craft is in an eccentric orbit with an apoasis altitude (the point at which it is furthest from the surface of Venus) of around 440,000km, and a periapsis altitude (the point at which it is closest to the surface of Venus) of around 400km. This is a considerably broader orbit than the mission had originally intended back in 2010, giving the vehicle an orbital period of around 13.5 days, the orbit slightly inclined relative to Venus’ equator.

In order to maximise the science return from the vehicle – which is now operating well in excess of its designed operational life – JAXA plan to use the next few months to gradually ease Akatsuki in an orbit which reduces both the apoasis distance from Venus, and bring down the orbital period to about 9 days.

These manoeuvres will likely be completed by April 2016, allowing the full science mission to finally commence. This is aimed at learning more about the atmosphere and weather on Venus as well as confirm the presence of active volcanoes and thunder, and also to try to understand exactly why Earth and Venus developed so differently from each other, despite being seen as sister planets in some regards.

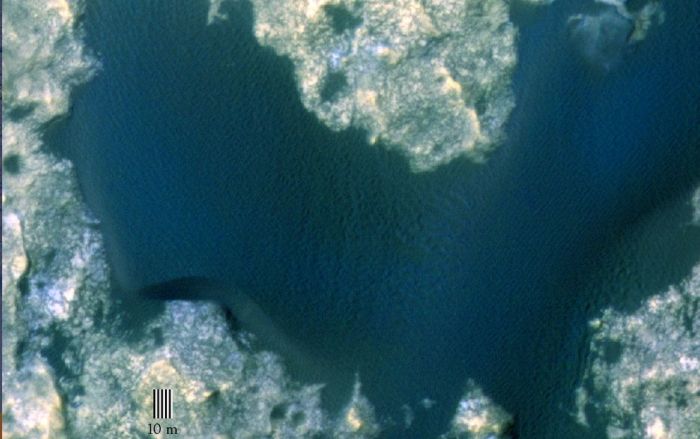

Even so, right from its arrival in its initial orbit, Akatsuki has been flexing its muscles, testing its imaging systems and returning a number of preliminary pictures of Venus to Earth, such as the ultra-violet image shown above right, captured just after the craft finally achieved orbit.

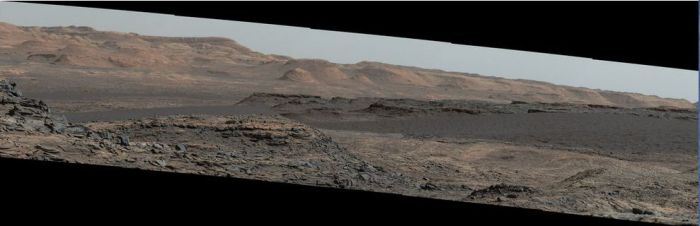

Curiosity reaches Sea of Sand

NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity has reached the edge of the major “sea” of sand dunes located on the flank of “Mount Sharp”. Dubbed the ““Bagnold Dunes” after British military engineer Ralph Bagnold, who pioneered the study of sand dune formation and motion, doing much to further the understanding of mineral movements and transport by wind action. Such studies are seen as an essential part of understanding how big a role the Marian wind played in depositing concentrations of minerals often associated with water across the planet, and by extension, the behaviour and disposition of liquid water across Mars.

Sand is not a new phenomenon for rovers on Mars to encounter – Curiosity, Opportunity and Spirit have all had dealings with it in the past; in fact Spirit’s mission as a rover came to an end in 2009, after it effectively got stuck in a “sand trap”. However, the “Bagnold Dunes” are very different to the sandy environs previously encountered by rovers; it is a huge “genuine” dune field where the sand hills can reach the height of 2-storey buildings and cover areas equivalent to an American football field.

So far, Curiosity has only probed the edge of the dune field around a sand hill originally dubbed “Dune 1”, and now called “High Dune”, using both its camera to image the region and its wheels to test the surface material prior to moving deeper into the sands. Wheel slippage is a genuine concern for the rover when moving on loose surfaces, as it can both overtax the motors and put the rover at risk of toppling over. Given this, and while there are no plans to attempt any ascent up the side of a dune, the mission team are taking things cautiously.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: clouds, sand, meteors and launches”

The Mars Science Laboratory rover, Curiosity, continues to climb the flank of “Mount Sharp” (formal name: Aeolis Mons), the giant mount of deposited material occupying the central region of Gale Crater around the original impact peak. For the last three weeks it has been making its way slowly towards the next point of scientific interest and a new challenge – a major field of sand dunes.

The Mars Science Laboratory rover, Curiosity, continues to climb the flank of “Mount Sharp” (formal name: Aeolis Mons), the giant mount of deposited material occupying the central region of Gale Crater around the original impact peak. For the last three weeks it has been making its way slowly towards the next point of scientific interest and a new challenge – a major field of sand dunes.