China has confirmed a series of ambitious new goals for its growing space endeavours, starting with the launch later this year of a new orbital facility, and progressing through 2018 with the launch of the core module for a large-scale space station, and which includes further mission to the Moon and to Mars.

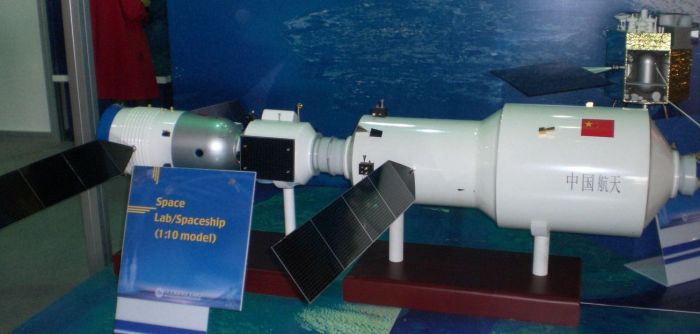

The first orbital facility launched by China, Tiangong-1 (“Heavenly Palace-1”), was launched in 2011. Referred to as a “space station”, the unit was more a demonstration test-bed for orbital rendezvous and docking capabilities. While it was visited by two crews in 2012 and 2013, neither stayed longer than 14 days, and sinc 2013, Tiangong-1 has operated autonomously, although it has suffered a series of telemetry failures in that time.

Tiangong-2 will be launched later in 2016, and is designed to build on the experiences gained with the original facility, helping to pave the way for China’s first “genuine” space station. In particular, Tiangong-2 will provide an experiments bay, improved living facilities for longer-during stays, and allow China to verify key technologies such as propellant refuelling while in orbit, and undertake fully automated docking activities using uncrewed vehicles, when the nation’s first automated resupply vehicle, Tianzhou-1 (“Heavenly Vessel-1”) docks with the facility in 2017.

Tiangong-2 will be followed, in 2018 by the launch of the larger Tianhe-1 (“Sky River-1”) unit, which will form the core module for China’s first dedicated space station. Over the four years from 2018, this will grow with the addition of up to three other pressurised modules, together with a docked “Hubble-class” space telescope. It be supported and maintained by automated re-supply mission from Earth using the Tianzhou, and provide living and working space for up to 6 crew,

Nor does it end there. At the end of March, I wrote about China’s aggressive approach to Mars exploration.

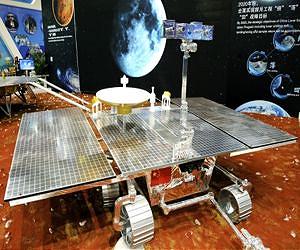

As a part of the series of announcements made by the Chinese authorities in the run-up to their first national Space Day on April 24th, 2016 – being the anniversary of the launch of China’s first satellite, Dongfanghong-1 (‘The East is Red’) – it was confirmed that the planned orbiter / rover mission to the red planet will be launched in 2020.

The rover element of the mission will build on experience gained during the deployment and operation of the Yutu vehicle on the Moon in 2013, and will be used to investigate the planet’s soil, atmosphere, environment, and look for traces of water.

As part of the preparations for this mission – although it is also a mission in its own right – China plans to land the its Chang’e-4 (“Moon Goddess”) probe, on the far side of the Moon in 2017, an operation which will be carried out fully autonomously of Earthside intervention.

To ensure all this happens, China is developing two new launch vehicle – the Long March 5 and the Long March 7. The Long March 5 will form the backbone of China’s space activities, offering a family of 6 launch vehicle variants, the largest of which will be capable of placing up to 25 tonnes in low Earth orbit (LEO), 14 tonnes in geosynchronous transfer orbit (GTO) for missions to the Moon, Mars or elsewhere, putting it in the same class of launch vehicles as America’s Atlas V and Delta IV launchers, and the commercial SpaceX Falcon 9 launcher.

Using non-toxic and pollution-free propellant, the 60-metre-long vehicle has a core diameter of 5 metres, and will be equipped with four strap-on booster 3.5 metres in diameter, Long March 5 is the first of China’s launch vehicles to specifically designed for both cargo / satellite launches and crewed mission launches. The maiden flight of the vehicle is expected to be the Chang’e-4 mission to the far side of the Moon.

The Long March 7 vehicle will be slightly smaller, capable of lifting 13.5 tonnes to LEO, although this will be enhanced over time to allow the vehicle to lift up to 20 tonnes to LEO. It will form the launch vehicle for the Tianzhou resupply missions to Tiangong-2 and Tianhe-1, and over time will be uprated to crewed launch vehicle status. It is slightly smaller than the Long March 5, with a height of 53 metres, a core diameter of 3.35 metres, and used 4 2.25 metre diameter liquid-fuelled strap-on boosters. The first launch of a Long March 7 vehicle is expected later in 2016, when it lifts Tianzhou-1 for a rendezvous with Tiangong-2.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: China’s ambitions, Dawn’s success and Kepler’s return”