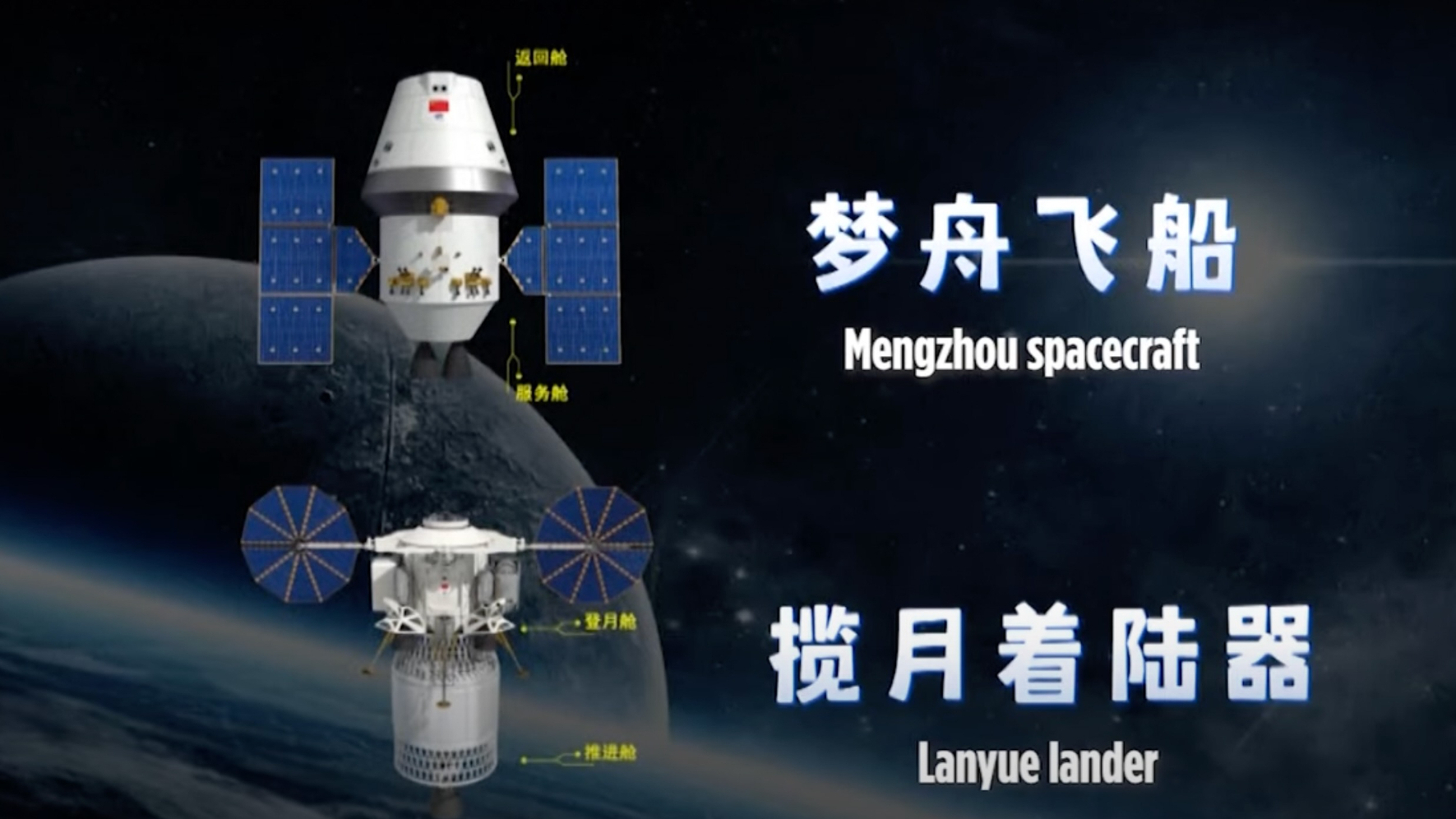

The China’s Manned Spaceflight Agency (CMSA) has revealed the names and preliminary drawings of the vehicles China plans to use to deliver its own astronauts – called taikonauts in Chinese – to the lunar South Polar Region.

For their human missions to the Moon, China is going the “easy” (that is, largely tested) way. No complicated drives to HALO orbits around the Moon and high-risk approaches such as 14 refuelling flights for the lunar lander after it has reached Earth orbit just so it can get to the Moon (yes, I’m looking at you, NASA – chuck the SpaceX idiocy, will you, please?). Instead, China is going a-la Apollo, using a two-ship system.

The first of these has been in development for a while, and has been referred to in the past as China’s “next generation crewed spacecraft” designed to replace the Soyuz-inspired Shenzhou vehicle the country currently uses to reach low Earth orbit, as well as forming a basis for excursions further afield – such as to the Moon.

As announced by via Chinese state media on February 24th, 2024 during the Lantern Festival – the last day of traditional Chinese new year festivities and which takes place, appropriately enough during a full Moon -, the new class of crewed space vehicle will now be called Mengzhou (“Dream Vessel”). The name was selected after China held a national competition to name the programme, and is in keeping with the naming convention for its orbital classes of space vehicle (e.g. Shenzhou and Tianzhou).

Mengzhou is a two-stage craft comprising a useable capsule system capable of seating up to six taikonaut, and an expendable service module providing propulsion, power and life support. The vehicle’s overdesign is fairly advanced: a scale model version of the capsule was flown in space in 2016 on a mission designed to provide engineers with the data they required to finalise the capsule’s overall design and flight characteristics.

A second flight in 2020 using a full-scale proof-of-concept vehicle used to evaluate vehicle avionics, orbit performance, new heat shielding, parachute deployment and a cushioned airbag landing and recovery system. Currently, the first crewed test flight of the craft in either 2026 or 2027.

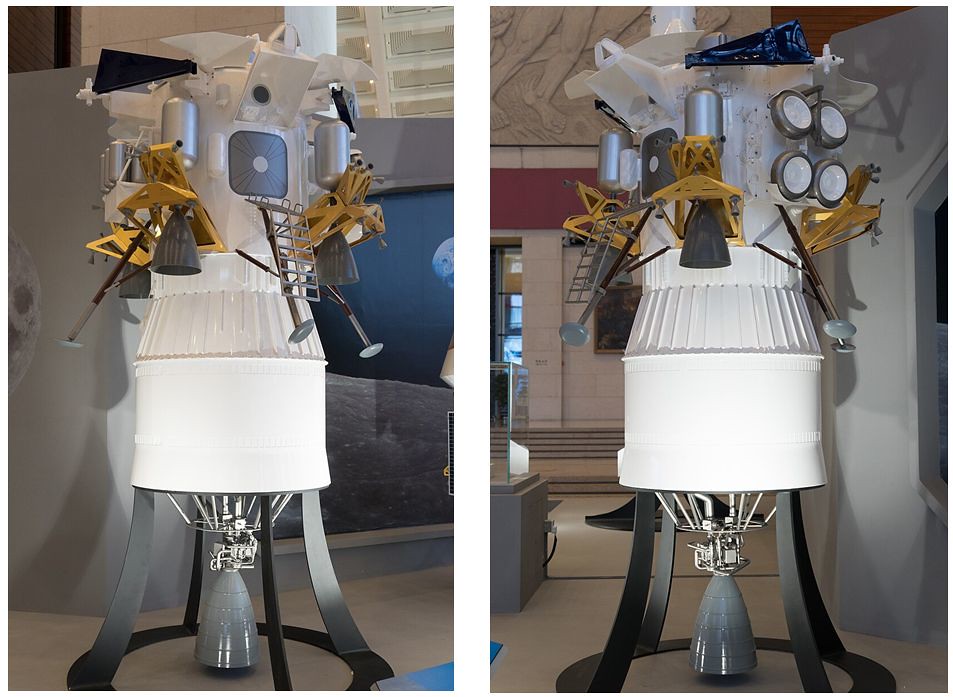

Four lunar missions, Mengzhou will fly with a crew of three and extended life support capabilities and additional supplies. It will be joined on missions by the Lanyue (“embracing the Moon”) lander. This again borrows somewhat from the Apollo missions of the late 1960s / early 1970s, being a spindly-legged craft built around a squat crew compartment supporting (initially) two taikonauts. Like the Apollo lunar lander, the craft is two staged; unlike the American lunar lander – which landed on the Moon fully intact, with the lower (“descent”) stage becoming a launch pad for the upper (“ascent”) stage for getting the crew back up to lunar orbit – Lanyue will use the same stage for both the landing and ascent phases of a mission.

The second stage of the vehicle will be a propulsion module which will power the lander to lunar orbit and then “park” it there. The crew will then travel to lunar orbit aboard a Mengzhou vehicle and dock with Lanyue. Two will transfer to the lander vehicle and undock to use the lander’s propulsion module to decelerate out of lunar orbit and into a descent towards the surface. Once the descent commences, the propulsion stage will be jettisoned to crash on the Moon, while the lander/ascent stage will continue on to a soft landing.

Information on how long a time the initial crews will spend on the Moon is unclear, as the details thus fair released are ambiguous in their interpretation. For example: the term “six hour stay” is used, but both in terms of the complete surface mission and in reference to crew EVA time. Most analysts in the west believe the first missions will equate to the stays of Apollo 11 and Apollo 12 – so “six hours” refers to actual EVA time -, with subsequent missions staying for increasingly extended periods, up to the limitations of the lander in terms of consumable supplies.

Plans for Lanyue include the provision of a collapsible rover vehicle of a similar nature to the Apollo Lunar Rover, and several models of the lander show the rover stored on its flank. However, it is not clear if it will be part of the first landing(s) or a subsequent addition to missions.

For lunar missions, both Mengzhou and Lanyue will be launched by China’s upcoming Heavy Lift Launch Vehicle (HLLV) Long March 10. Due to make a maiden flight possibly as early as the latter half 2025, this booster is an evolution of China’s Long March 5, and is slated to be able to deliver up to 70 tonnes to LEO or send up to 27 tonnes on its way to the Moon. As noted above, each lunar mission will comprise two Long March 10 launches, one for the lander vehicle and its propulsion module, and one for the crewed vehicle. In addition and when used on Earth orbital missions, elements of the Long March 10 might be evolved to be reusable.

Currently, China is looking at 2030 for their first crewed landing on the Moon, with subsequent mission intended to establish a research outpost in the lunar South Polar Region. From around 2034/35 onwards, China claims this outpost will be expanded into a permanently occupied base open to all countries joining its International Lunar Research Station Cooperation Organization (ILRSCO), seen as a direct alternative / “competitor” to the American-lead Artemis Programme.

One Lander Goes to Sleep, Another Unexpectedly Awakens

They are in many ways the joint tale of two lunar landers, both of which suffered mishaps as they arrived on the Moon, and both of which have nevertheless met the majority of their mission expectations.

Japan’s SLIM

On January 19th, 2024, the Japanese Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM – also called “Moon Sniper”) arrived on the lunar surface – upside down (see Space Sunday: a helicopter that could; a lander on its head). Despite this, the landing meant Japan had become only the fifth nation to successfully land a vehicle on the Moon after America, Russian and India, and the mission carried out most of its assigned science despite being inverted, prior to the long lunar night (14 terrestrial days long) settling over it.

Lacking sunlight to provide energy for its batteries, the chances of SLIM making it through the long, cold night were low, but the mission team at JAXA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, powered-down the craft ahead of night arriving in the hopes its batteries might retain sufficient power to keep the electronics warm until the Sun rose over the landing site once more.

On February 25th, this optimism was rewarded: following sunrise over SLIM, the team were able to establish contact – albeit it intermittently. Attempts were then made to resume some of the lander’s science work, notably with the multiband spectroscopic camera (MBC). Unfortunately, these were unsuccessful, mission engineers believing MBC may have suffered damage as a result of the extreme low night-time temperatures.

Attempts to engage the system were abandoned on February 29th when, with night again approaching, SLIM was once again ordered to go to sleep in the hope its batteries will again see it through to the next lunar midday period in the latter part of March, when the sunlight will again be directly on its solar array.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: More Moon (with people!) and a bit of Mars”