On August 15th, I wrote about rumours that an “Earth-like” planet has been found orbiting our nearest stellar neighbour, Proxima Centauri, 4.25 light years away from our own Sun. The news was first leaked by the German weekly magazine, Der Spiegel, which indicated the discovery had been made by a team at the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) La Silla facility – although ESO refused to comment at the time.

However, during a press conference held on August 24th, ESO did confirm the detection of a rocky planet orbiting Proxima Centauri. Dubbed Proxima b, the planet lies within the so-called “Goldilocks” habitable zone around its parent star – the orbit in which conditions are “just right” for the planet to harbour liquid water and offer the kind of conditions in which life might arise.

The ESO data reveals that Proxima b is orbits its parent star at a distance of roughly 7.5 million km (4.7 million miles), at the edge of the habitable zone, and does so every 11.2 terrestrial days and is about 1.3 times as massive as the Earth. The discovery came about by comparing multiple observations of the star over extended periods using two instruments at La Silla to look for signs of the star “wobbling” in its own spin as a result of planetary gravitational influences. Once identified, ESO called on other observatories around the world to carry out similar observations / comparisons to confirm their findings.

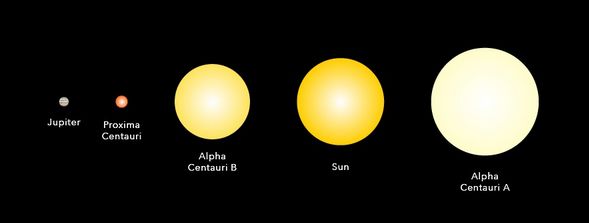

Although the planet lies within the “Goldilocks zone”, just how habitable is it likely to be is still open to question. Stars like Proxima Centauri, which is roughly one-seventh the diameter of our Sun, or just 1.5 times bigger than Jupiter, are volatile in nature, all activity within them entirely convective in nature, giving rise to massive stellar flares. As Proxima-B orbits so close to the star, it is entirely possible that over the aeons, such violent outbursts from Proxima Centauri have stripped away the planet’s atmosphere.

In addition, the preliminary data from ESO suggests the planet is either tidally locked to Proxima Centauri, or may have a 3:2 orbital resonance (i.e. three rotations for every two orbits) – either of which could make it an inhospitable place for life to gain a toe-hold. The first would leave one side in perpetual daylight and the other in perpetual night, while the second would limit any liquid water on the surface to the tropical zones.

Nevertheless, the discovery of another world in one part of our stellar backyard does raise the question of what NASA’s upcoming TESS mission might find when it starts searching the hundreds of nearby stars for evidence of exoplanets in 2018.

Juno’s Second Pass Over Jupiter

NASA’s Juno space craft made a second successful close sweep over the cloud-tops of Jupiter on Saturday, August 27th to complete its first full orbit around the planet. Speeding over the planet at a velocity of 208,000 km/h (130,000 mph) relative to Jupiter, Juno passed just 2,400 km (2,600 miles) above the cloud tops before heading back out into space, where it will again slowly decelerate under the influence of Jupiter’s immense gravity over the next 27 days, before it once again swing back towards the gas giant.

“Early post-flyby telemetry indicates that everything worked as planned and Juno is firing on all cylinders,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, as telemetry on the flyby started being received on Earth some 48 mins after the flyby, which occurred at 13:44 UTC.

All of Juno’s science suite was in operation during the passage over Jupiter’s clouds. However, due to speed at which the gathered data can be returned to Earth, and given it cannot all be relayed in one go or necessarily continuously, it will be a week or more before everything has been transmitted back to Earth. Nevertheless the science team are already excited by the flyby.

“We are getting some intriguing early data returns as we speak,” Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute, stated. Some of that data included initial images of Jupiter captured as Juno swept towards the planet during the run-up to periapsis. “We are in an orbit nobody has ever been in before, and these images give us a whole new perspective on this gas-giant world,” Bolton added.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: exoplanets, dark matter, rovers and recoveries”