Wednesday, November 12th saw a remarkable feat take place over 515,000,000 kilometres from Earth as a small robotic vehicle called Philae, and a part of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission, landed on the surface of a comet, marking the very first time this has ever been achieved.

As I reported, immediately following the landing, getting a vehicle to rendezvous with a comet, enter orbit around it and deploy a lander to its surface isn’t easy – Rosetta is a mission 21 years old, with the spacecraft spending a decade of that time flying through space.

Immediately following the landing, telemetry revealed things hadn’t gone to plan, although the lander itself was unharmed. Essentially, part of the landing system – a pair of harpoons designed to tether the lander to the comet’s surface as a direct result of the very weak gravity there – failed to operate as expected. Telemetry has shown that the tensioning mechanism and the harpoon activation process started, but the harpoons themselves did not fire. As a result, the vehicle actually “bounced” after its initial touch-down.

The initial touch-down was at 15:33 UT – precisely on schedule and on target. However, as the harpoons failed, the lander rose back up – possibly by as much as a kilometre – above the comet, before finally striking the surface again, two hours later. This means that even while celebrations over the initial landing were going on here on Earth (the initial signal confirming touchdown taking some 30 minutes to reach Earth), Philae had yet to make its second contact with the comet.

This eventually happened at 17:26 UT, and was followed by another bounce, this one of a much lesser force, before the lander came to rest at 17:33 UT.

One of the consequences of this bouncing is that the lander is not actually in its designated landing zone – the comet is tumbling through space, and thus turning under the lander as it bounced. This means that while Rosetta and Philae are communicating with one another, the spacecraft’s orbital position around the comet is not optimal for the lander’s position, and is being refined to better suit Philae’s new location. An initial adjustment was made overnight on the 12th/13th November, and further adjust is likely to be made on Friday, November 14th. Currently, communications can occur between the two vehicles for just under 4 hours out of every 13.

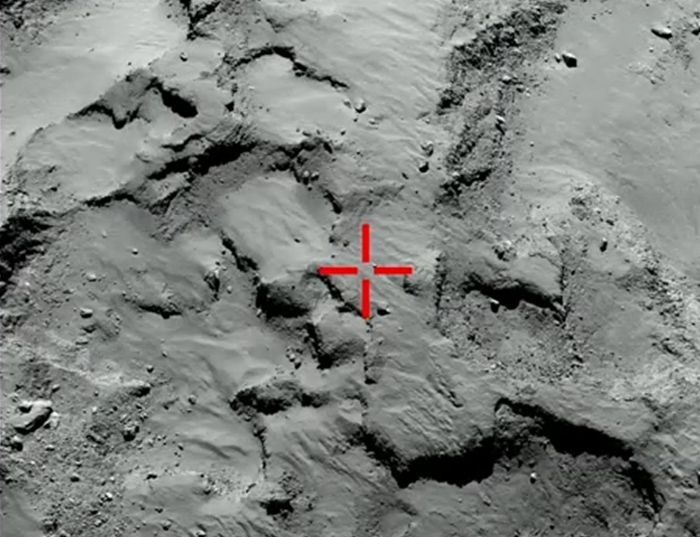

This bouncing may explain why there was an initial problem with communications between the lander and the Rosetta spacecraft, as reported immediately after the initial landing telemetry was received: Rosetta was expecting Philae to be at a certain fixed position on the comet, whereas the lander was still in motion, and “moving away” from the landing site as the comet rotated. The task now is for Rosetta to visually locate the lander – which given the current orbital positioning, may take a little time; the next passage of the spacecraft over the region of the landing site will not start until 19:27 UT this evening. Mission planners hope the sunlight reflected by the lander’s solar panels might help in identifying Philae’s exact position.

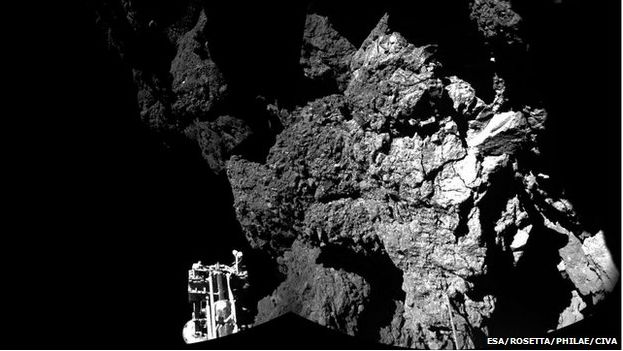

A core worry for the mission team is that Philae has in fact come down in an area of shadow, possibly in a depression and close to one or two rocky “walls”, and it appears to only be receiving direct sunlight for around 90-120 mins as the comet tumbles, rather than the 6-7 hours planned with the target landing point. This potentially has serious implications for the lander’s power and science regime, although it is hoped that Philae might be able to adjust its position somewhat – the craft actually has the capability of “hopping” around by flexing its landing legs.

However, “hopping” isn’t an option at present, as the mission team have no clear idea precisely where the lander is, or the lay of the land immediately around it; until more is known, the lander will not be physically relocated. A further issue here is that while the lander is secure on the surface, not all of the leg may actually be in contact with the comet’s surface, which could lead to unexpected results were the lander be ordered to “hop”.

This uncertainty about the lander’s overall position on the comet, coupled with the non-firing of the harpoons means that the drill system cannot be used without further understanding of the vehicle’s situation, as doing so could adversely affect the lander, possibly tipping it over. This means that it is unlikely any drilling and sample-gathering, an essential part of the mission – probably will take place until Friday, November 14th.

The problem here is, again, that the lander has limited power on its primary batteries, and with the solar power system unable to provide the levels of power required, high-energy systems such as the drill may not be able to operate much beyond Friday, November 14th.

This doesn’t mean the mission would be a failure – the lander has sufficient power to operate most of its instruments over the next 24 hours or so. Also, it may be that the lander’s situation vis. solar power can be improved. And, of course, Rosetta is still in orbit around the comet, and still fully capable of carrying out its long-term mission.

This is very much an unfolding mission, so the situation is likely to change as more data is obtained by the mission team. I’ll have further updates (for those interested) over the next few days.

Related Links

All images courtesy of the European Space Agency unless otherwise indicated.