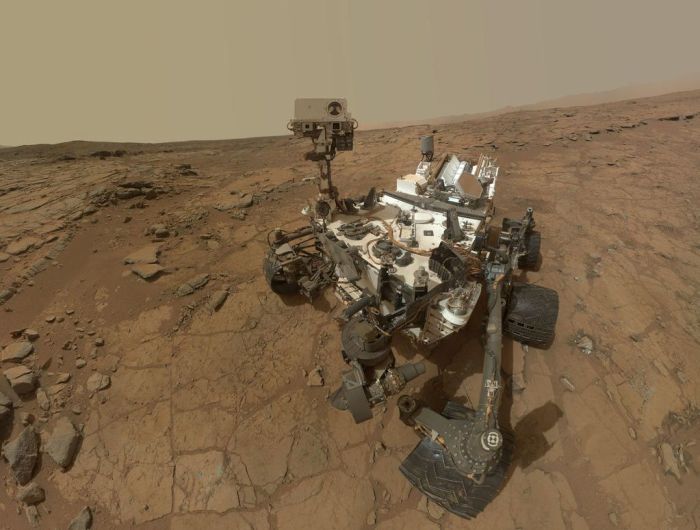

Curiosity, the Mars Science Laboratory rover, resumed operations on Mars resumed operations on March 11th 2015, after an electrical short circuit in the rover’s robot arm caused a suspension of activities while the matter was investigated, and short itself having triggered the rover to switch to a “safe” mode to prevent any potential damage.

Curiosity, the Mars Science Laboratory rover, resumed operations on Mars resumed operations on March 11th 2015, after an electrical short circuit in the rover’s robot arm caused a suspension of activities while the matter was investigated, and short itself having triggered the rover to switch to a “safe” mode to prevent any potential damage.

The short, was not enough to damage the rover’s electrical systems in any way, occurred occurred when the was attempting to transfer samples of material gathered from a rock dubbed “Telegraph Peak” from the drill head to the CHIMRA system by subjecting the entire turret to rapid vibrations from the drills percussion action. Extensive tests were carried out over 10 days to try to determine if the short was transient, or indicative of a potential fault. Only one test during this time caused a further short, which lasted around 1/100th of the second, and didn’t interrupt the drill motor.

The results of the tests gave engineers a high degree of confidence that the short wasn’t indicative of the major fault developing, and so operations recommenced on March 11th with the transfer of some of the “Telegraph Peak” material being delivered to the rover’s on-board laboratory while analysis of the results from the tests carried out on the drill mechanism continue to be examined.

As Curiosity now heads on up the slopes of “Mount Sharp”, aiming to pass through a shallow valley dubbed “Artist’s Drive”, NASA has confirmed that the rover has found “biologically useful nitrogen” on Mars.

Nitrogen is essential for all known forms of life, since it is used in the building blocks of larger molecules like DNA and RNA, which encode the genetic instructions for life, and proteins, which are used to build structures like hair and nails, and to speed up or regulate chemical reactions. On Earth and Mars, however, atmospheric nitrogen is locked up as nitrogen gas (N2) – two atoms of nitrogen bound together so strongly that they do not react easily with other molecules; they have to become “fixed” (separated) in order to participate in the chemical reactions needed for life.

On Earth, certain organisms are capable of fixing atmospheric nitrogen and this process is critical for metabolic activity. However, smaller amounts of nitrogen can also be fixed by energetic events like lightning strikes.

While Nitrogen has long been known to exist on Mars, a study by the NASA team supporting the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) experiment onboard the rover reveals that NO3, a nitrogen atom bound to three oxygen atoms and a source of “fixed” nuitrogen has been found in numerous samples gathered by the rover during its journey across Gale Crater.

Although the report’s authors make it clear that there is no evidence to suggest that the fixed nitrogen molecules they’ve discovered were created by life. The confirmation that NO3 does exist adds significant weight to the potential for Mars once having the kind of environment and building blocks needed by life. This is particularly relevant, given that one of the areas in which the NO3 was identified is the “Yellowknife Bay” area, which Curiosity examined in early 2013, and which was shown to have once had a very benign environment for life processes, complete with water, many of the right chemicals, and a local source of energy. This prompted Jennifer Stern of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland, and a co-author f the report to note, “Had life been there, it would have been able to use this nitrogen.”

However, it is more likely that the fixed nitrogen that has been discovered may have been generated primarily by the numerous powerful impacts that occurred about 4 billion years ago, during a period known as the Late Heavy Bombardment, when the inner planets of the solar system were “hoovering up” the remaining debris of asteroids and rock scattered across their orbits. That said, “fixed” nitrogen has also been detected high in the modern day Martian atmosphere by Europe’s Mars Express. What’s missing at the moment is the capability to get a big enough nitrate signal for any nitrogen isotope data which might exist, as none of the experiments on Mars are broad enough to do so, thus this is likely to be something future missions to Mars will consider.