New Horizons is still less than half way through transmitting the data gathered during its fly-past of the Pluto-Charon system in July 2015, but the wealth of information received thus far has already revealed much about Pluto and its “twin”.

New Horizons is still less than half way through transmitting the data gathered during its fly-past of the Pluto-Charon system in July 2015, but the wealth of information received thus far has already revealed much about Pluto and its “twin”.

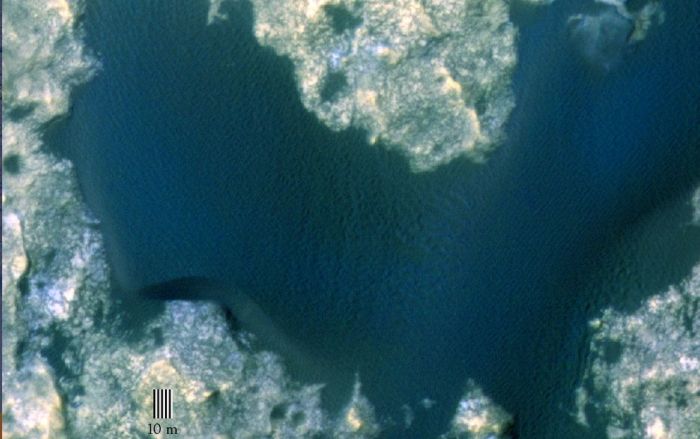

Geological evidence has been found for widespread past and present glacial activity, including the formation of networks of eroded valleys, some of which are “hanging valleys,” much like those in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. A major part of this activity is occurring in and around “Sputnik Planum”, the left half of Pluto’s “heart”, a 1,000 km (620 mile) wide basin, which is seen as key to understanding much of the current geological activity on Pluto.

Images and data gathered for this region has given rise to new numerical models of thermal convection with “Sputnik Planum”, which is formed by a deep layer of solid nitrogen and other volatile ices. These not only explain the numerous polygonal ice features seen on Sputnik Planum’s surface, but suggest the layer is likely to be a few kilometres in depth.

Evaporation of this nitrogen, together with condensation on higher surrounding terrain is believed causing a glacial flow from the higher lands back down into the basin, where the ice already there is pushed, reshaping the landscape over time.

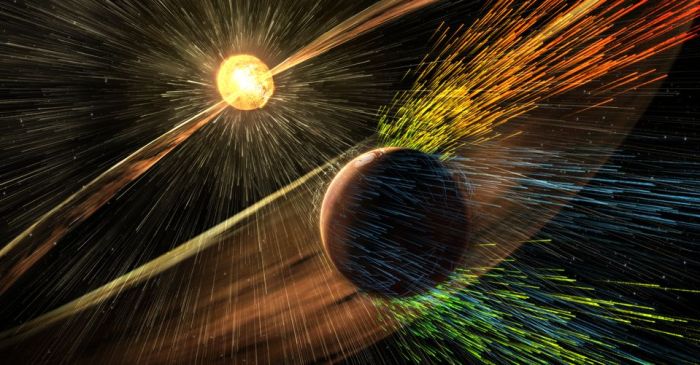

More data and images have also been received regarding Pluto’s atmosphere, allowing scientists start to probe precisely what processes are at work in generating and renewing the atmosphere, the upper limits of which are subject to erosion by the solar wind, which strike Pluto at some 1.4 million kilometres per hour (900,000 mph).

As well as understanding the processes which are at work renewing the atmosphere, and thus preventing it from being completely blasted away by the solar wind, science teams are hoping to better further why the haze of Pluto’s atmosphere forms a complicated set of layers – some of which are the result of the formation and descent of tholins through the atmosphere – and why it varies spatially around the planet.

The Mars Silica Mystery

In July I covered some of the work going into investigating the mystery of silica on Mars. This is a mineral of particular interest to scientists because high levels of it within rocks could indicate conditions on Mars which may have been conducive to life, or which might preserve any ancient organic material which might be present. In addition.

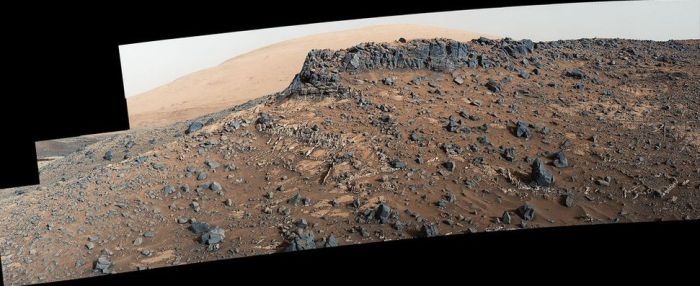

As I reported back in July, scientists have been particularly interested in the fact that as Curiosity has ascended “Mount Sharp”, so have the amounts of silica present in rocks increased: in some rocks it accounts for nine-tenths of their composition. Trying to work out why this should be, and identifying the nature of some of the silica deposits has given rise to a new set of mysteries.

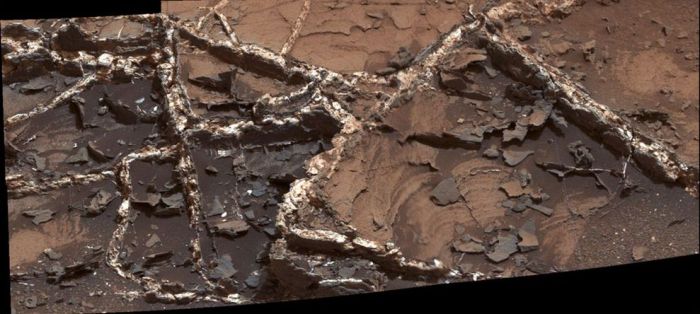

The first mystery is trying to understand how the silica was deposited – something which could be crucial in understanding how conducive the environment on “Mount Sharp” might have been for life. Water tends to contribute to silica being deposited in rocks in one of two ways. If it is acidic in nature, it tends to leach away other minerals, leaving the silica behind. If it is more neutral or alkaline in nature, then it tends to deposit silica as it filters through rooks.

If the water which once flowed down / through “Mount Sharp” was acidic in nature, it would likely mean that the wet environments found on the flanks of the mound were hostile to life having ever arisen there or may have removed any evidence for life having once been present. If evidence that the water was acidic in nature, then it would also possibly point to conditions on “Mount Sharp” may have been somewhat different to those found on the crater floor, where evidence of environments formed with more alkaline water and with all the right building blocks for life to have started, have already been discovered.

The second mystery with the silica is the kind of silica which has been discovered in at least one rock. Tridymite is a polymorph of silica which on Earth is associated with high temperatures in igneous or metamorphic rocks and volcanic activity. Until Curiosity discovered significantly high concentrations of silica in the “Marias Pass area of “Mount Sharp” some seven months ago – something which led to a four month investigation of the area – tridymite had never been found on Mars.

“Marias Pass” and the region directly above it, called the “Stimson Unit” show some of the strongest examples of silica deposition on “Mount Sharp”, and it was in one of the first rocks, dubbed “Buckskin”, exhibiting evidence of silica deposits in which the tridymite was found.

The question now is: how did it get there? All the evidence for the formation of “Mount Sharp” points to it being sedimentary in nature, rather than volcanic. While Mars was very volcanic early on in its history, the presence of the tridymite on “Mount Sharp” might point to volcanic / magmatic evolution on Mars continuing for longer than might have been thought, with the mineral being deposited on the slopes of the mound as a result of wind action. Or alternatively, it might point to something else occurring on Mars.

Continue reading “Space Update: silica mysteries, Brits in space and tracking Santa”

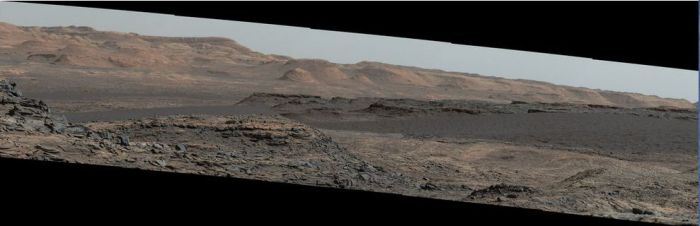

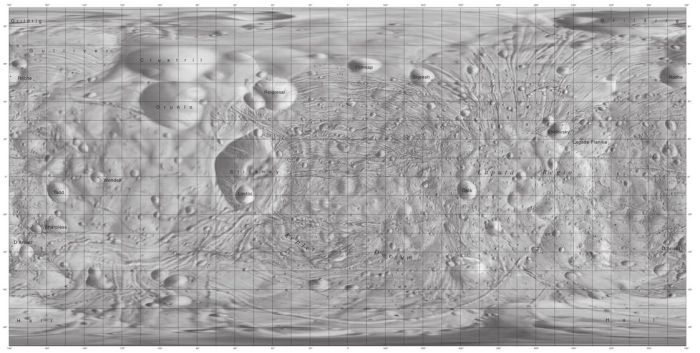

The Mars Science Laboratory rover, Curiosity, continues to climb the flank of “Mount Sharp” (formal name: Aeolis Mons), the giant mount of deposited material occupying the central region of Gale Crater around the original impact peak. For the last three weeks it has been making its way slowly towards the next point of scientific interest and a new challenge – a major field of sand dunes.

The Mars Science Laboratory rover, Curiosity, continues to climb the flank of “Mount Sharp” (formal name: Aeolis Mons), the giant mount of deposited material occupying the central region of Gale Crater around the original impact peak. For the last three weeks it has been making its way slowly towards the next point of scientific interest and a new challenge – a major field of sand dunes.