Update, July 5th: The insertion burn on July 4th/5th was successful, and Juno is safely in its initial orbit around Jupiter. I’ll have an update on the mission in the next Space Sunday.

Update, July 5th: The insertion burn on July 4th/5th was successful, and Juno is safely in its initial orbit around Jupiter. I’ll have an update on the mission in the next Space Sunday.

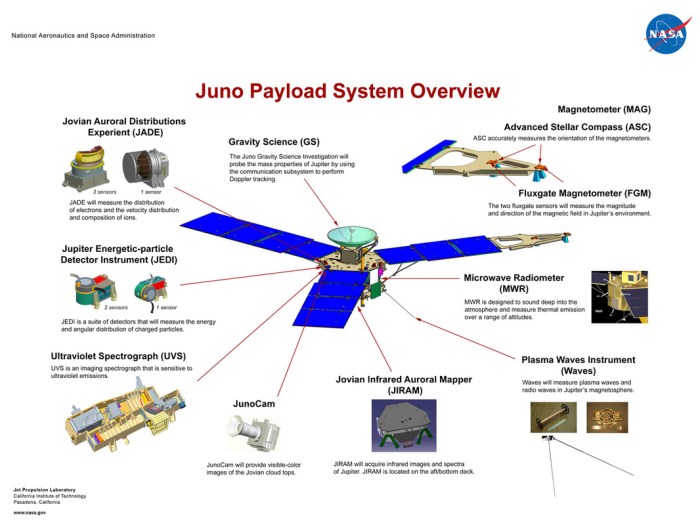

rAt 20:18 PDT on Monday, July 4th (03:18 UT, Tuesday, July 5th) a spacecraft called Juno will fire its UK-built Leros-1b engine to commence a 35-minute burn designed to allow the spacecraft enter an initial orbit around the largest planet in the solar system, ready to begin a comprehensive science campaign.

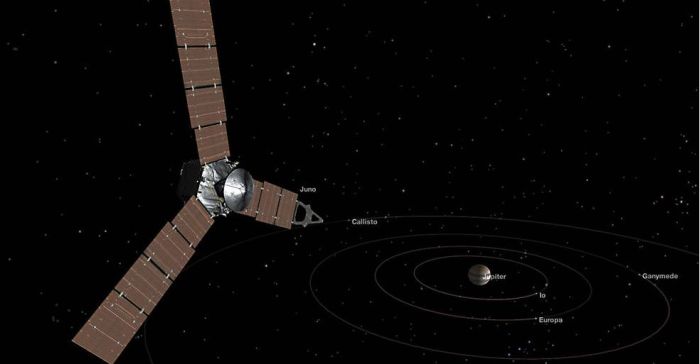

As I write this, the craft is already inside the orbit of Callisto, the furthest of Jupiter’s four massive Galilean satellites, which orbits the planet at a distance of roughly 1.88 million kilometres. During the early hours of July 4th, (PDT), the vehicle will cross the orbits of the remaining three Galilean satellites, Ganyemede, Europa and Io, prior to commencing its orbital insertion burn.

In the run-up to the burn, Juno will complete a series of manoeuvres designed to correctly orient itself to fire the Leros-1b, which will be the third of four planned uses of the engine in order to get the craft into its final science orbit. Two previous burns of the engine – which NASA regards as one of the most reliable deep space probe motors they can obtain – in 2012 ensured the craft was on the correct trajectory from this phase of the mission.

Getting into orbit around Jupiter isn’t particularly easy. The planet has a huge gravity well – 2.5 times greater than Earth’s. This means that an approaching spacecraft is effectively running “downhill” as it approaches the planet, accelerating all the way. In Juno’s case, this means that as the vehicle passes north-to-south around Jupiter for the first time, it will reach a velocity of nigh-on 250,000 kph (156,000 mph), making it one of the fastest human-made objects ever.

Slowing the vehicle directly into a science orbit from these kinds of velocities would take an inordinate amount of fuel, so the July 4th manoeuvre isn’t intended to do this. Instead, it is designed to hold the vehicle’s peak accelerate at a point where although it will be thrown around Jupiter and back into space, it will be going “uphill” against Jupiter’s gravity well, decelerating all the time. So much so, that at around 8 million kilometres (5 million miles) away from Jupiter, and travelling at just 1,933 kph (1,208 mph), Juno will start to “fall back” towards Jupiter, once more accelerating under gravity, to loop around the planet a second time on August 27th, coming to within (4,200 km (2,600 mi) of Jupiter’s cloud tops, before looping back out into space.

On October 19th, Juno will complete the second of these highly elliptical orbits, coming to within 4,185 km (2,620 mi) of the Jovian cloud tops as it completes a final 22-minute burn of the Leros-1b motor. This will be sufficient for Jupiter’s gravity to swing Juno into an elliptical 14-orbit around the planet, passing just 4,185 km from Jupiter at its closest approach before flying out to 3.2 million kilometres (2 million miles) at it’s furthest from the planet.

The July 4th insertion burn is also significant in that it marks the end of a 5-year interplanetary journey for Juno, which has seen the vehicle cover a distance of 2.8 billion km (1.74 billion miles).

It’s a voyage which began on August 5th, 2011, atop a United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V, launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida.

As powerful as it is, the Atlas isn’t powerful enough to send a payload like Juno directly to Jupiter. Instead, the craft flew out beyond the orbit of Mars before dropping back to Earth, passing us again in October 2013 and using Earth’s gravity to both accelerate and to slingshot itself into a Jupiter transfer orbit.

While, at 35 minutes, the engine burn for orbital insertion is a long time, the distance from Juno to Earth means that confirmation that the burn has started will not be received until 13 minutes after the manoeuvre has actually completed. That’s how long is takes for a radio signal to travel from the vehicle back to Earth (and obviously, for instructions to be passed from Earth to Juno. Thus, the manoeuvre is carried out entirely automatically by the vehicle

Juno is not the first mission to Jupiter, but it is only the second orbital mission to the giant of the solar system.

The Jovian system was first briefly visited by Pioneer 10 in 1973, followed by Pioneer 11 a year later. Both of these were deep space missions (which are still continuing today), destined to continue outward through the solar system and into interstellar space beyond. They were followed by the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 missions in January and July 1979 respectively, again en route for interstellar space by way of the outer solar system.

In 1992 the Ulysses solar mission used Jupiter as a “slingshot” to curve itself up into a polar orbit around the Sun. Then in 2000, the Cassini mission used Jupiter’s immense gravity to accelerate and “bend” itself towards Saturn, its intended destination. New Horizons similarly used Jupiter for a “gravity assist” push in 2007, while en route to Pluto / Charon and the Kuiper Belt beyond.

It was in 1995 that the first orbital mission reached Jupiter and its moons. The nuclear RTG-powered Galileo was intended to study Jupiter for just 24 months. However, it remained largely operational until late 2002 before the intense radiation fields around the planet took their final toll on the vehicle’s systems. Already blind, and with fuel supplies dwindling, Galileo was ordered to crash into the upper limits of Jupiter’s atmosphere in 2003, where it burned up.

In the eight years it operated around Jupiter, Galileo complete changed our perspective on the planet. Juno has a 20-month primary mission, and it is hoped its impact on our understanding of Jupiter will be greater than Galileo’s. However, it is unlikely the mission will be extended.

Unlike all of NASA’s previous missions beyond the orbit of Mars, which have used RTG power units, Juno is entirely solar-powered, making it the farthest solar-powered trip in the history of space exploration. However, the three 8.9 metre (29 ft) long, 2.7 metre (8.9 ft) wide solar panels are particularly vulnerable to the ravages of radiation around Jupiter, and it is anticipated that by February 2018, their performance will have degraded to a point where they can no longer generate the levels of electrical energy required to keep the craft functioning – if indeed, its science instruments and electronics haven’t also been damaged beyond use by radiation. This being the case, Juno will be commanded to fly into Jupiter’s upper atmosphere and burn up.