Mercury, the closest planet in our solar system to the Sun, is hardly the kind of place where you’d expect to find water ice. With surface temperatures reaching 400º C (750º F) on its sunlit side, the planet is fairly constantly broiled by the Sun. And yet NASA’s MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) mission did actually confirm ice on Mercury in 2012.

As with ice on the Moon, this water ice is located in deep craters around Mercury’s poles where the Sun never shines. What’s more, it appears to be created through a similar process and the lunar water ice; however, and in what may seem to be a counter-intuitive fact, the greater heat Mercury endures means it has far more ice located in its polar craters than the Moon.

It goes like this, electrically charged particles from the Sun’s solar wind interact with the oxygen present in some dust grains on the surface to produce hydroxyl (OH – a single hydrogen atom and a single oxygen atom). This hydroxyl bonds in groups within Mercury’s surface material, just as they do on the Moon.

On both the Moon and Mercury, heat from the Sun both frees these hydroxyl groups and energises them, causing collisions that that produce free hydrogen and water molecules. Some of these water molecules are broken down by sunlight and dissipate. But others descend into deep, dark polar craters that are shielded from the Sun. Here they freeze to become a part of the growing, permanent glacial ice housed in the shadows.

However, because Mercury is so much closer to the Sun, the greater exposure to the solar wind and – more importantly – greater heat means that the production and release of hydroxyl means that the production of hydrogen and water molecules is much greater – and some is the volume of those molecules falling into polar craters. Thus, the production of water ice on Mercury is much more pronounced – so pronounced that it is estimated some 10,000,000,000,000 kg (11,023,110,000 tons) of ice is generated over the course of 3 million years, cumulatively enough to account for around 10% on the total ice found on and under the surface of Mercury – the rest having being delivered via asteroid bombardment in the planet’s early history.

The process of the ice falling into the craters is a little like the song Hotel California. The water molecules can check in to the shadows, but they can never leave.

– Thom Orlando, Georgia Tech, a co-author of a new study into water ice on Mercury

Starliner: 61 Changes Required

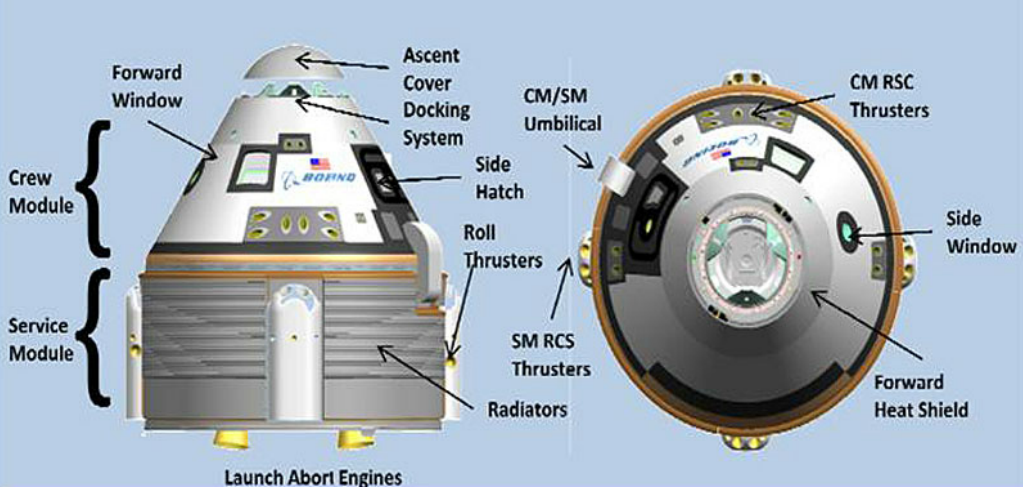

On Friday, December 20th, 2019, NASA and Boeing, together with launch partner United Launch Alliance (ULA), attempted to undertake the first flight of the Boeing CST-100 Starliner commercial crew transportation system to the International Space Station (ISS).

The mission – called Orbital Flight Test-1 (OFT-1) should have seen the uncrewed Starliner craft achieve orbit and then rendezvous with the ISS, where it would dock and spend several days there before making a return to Earth and a parachute landing in the Mojave desert.

While, as I reported in Starliner’s first orbital flight, the majority of the mission was a success – the vehicle achieved orbit and was able to carry out as series of orbital tests before returning safely to a soft landing, issues with the craft meant the capsule incorrectly initiated a series of firings of the vehicle’s attitude control system (ACS) when they were not required. By the time the errors were corrected, the vehicle had insufficient fuel reserves left in the ACS system tanks to achieve a safe docking with the station, thus causing the rendezvous to be abandoned.

Since then, NASA and Boeing have been investigating the root cause of the ACS timing misfiring. The results of these investigations identified both technical and organisational issues within Boeing’s management of the CST-100 programme. At the same time, a NASA internal review identified several areas where the agency could make improvements with regard to its participation in the production and testing of Orion capsules.

In all, some 61 corrective actions have been identified by NASA that Boeing need to make to both the processing of Orion vehicles and in their flight management organisation. These include gaps in processes that prevented ground-based mission controllers identifying what had gone wrong with OFT-1 in order to initiate corrective action that might have allowed the vehicle to go forward with its rendezvous with the ISS.

Boeing has accepted all 61 recommendations from NASA, and has started to implement them. At the same time, it has indicated it is to overhaul all of its testing, review, and approval processes for CST-100 hardware and software, and institute changes with its engineering board authority. NASA also plans to perform an Organisation Safety Assessment (OSA) of the workplace culture at Boeing prior to any future CST-100 flights.

While there was no crew aboard the test vehicle, NASA has nevertheless designated the flight a “high visibility close call” in accordance with their own procedural requirements. This means that while it is unlikely they would have threatened a crew had they been aboard (in fact, a crew would likely have been able to immediately respond to the ACS issue and correct it) the anomalies during the flight were simply too big to ignore, and could have led to serious consequences under different circumstances.

No date has yet been confirmed for the second orbital flight for a Starliner vehicle. This is due to deliver a crew of three NASA astronauts (Nicole Mann, Mike Fincke and Christopher Ferguson) to what might yet be an extended stay at the ISS in what is regarded as the final test flight for the CST-100.

The first “operational” flight for Orion will comprise NASA personnel: mission commander Sunita Williams and Josh Cassada, ESA astronaut Thomas Pesquet and cosmonaut Andrei Borisenko. This flight will see the vehicle used in OFT-1 re-used as part of NASA’s plans to fly each CST-100 a number of times. Commander Williams was on hand to witness the vehicle’s return to Earth at the end of OFT-1, and she named the vehicle Calypso.