It’s been a while since there has been any major news from NASA’s Curiosity rover as it explores “Mount Sharp” in Gale Crater.

It’s been a while since there has been any major news from NASA’s Curiosity rover as it explores “Mount Sharp” in Gale Crater.

The last time I covered the rover’s activities, it was investigating a series of sand dunes which are slowly descending down the slopes of “Mount Sharp” as a result of a combination of gravity and wind action.

This work was completed in March, when the rover resumed its progress up the flank of the mound, climbing onto “Naukluft Plateau”, a roughly flat area cut into the side of “Mount Sharp” where aeons of wind erosion has carved the sandstone bedrock into ridges and knobs which were thought could offer a challenge for the rover in terms of wear and tear on the wheels.

The plateau lay between the rover and the next major area of scientific interest for the mission, so the drive team have been edging the rover across the rough terrain in the hope of reaching smoother ground on which it can continue upwards without exposing its six aluminium wheels to risk of severe damage.

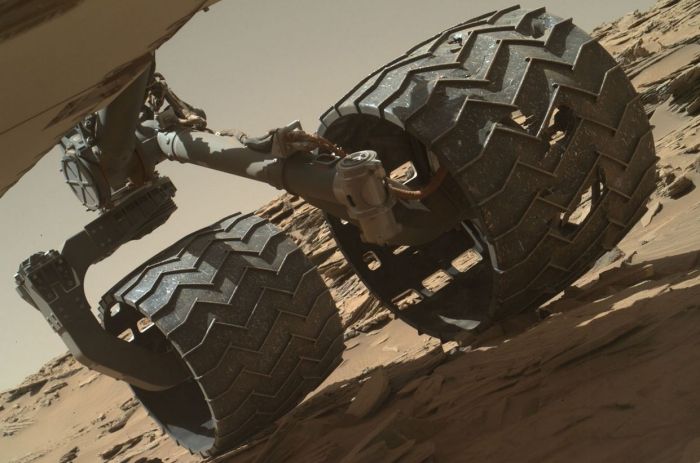

The roughness of the terrain on the plateau had raised concern that driving on it could be especially damaging to Curiosity’s wheels, as it is very similar to terrain the rover crossed in 2013 while en route to “Mount Sharp”, resulting in visible damage to some of Curiosity’s wheels, punching holes and tears into the aluminium, and prompting the mission team to undertake extensive tests on the wheels and their performance following such damage, using a duplicate of the rover here on Earth.

Because of the previous damage caused to the wheels, Curiosity was instructed to periodically image the condition of its wheels during the drive, a process which slowed progress but also revealed any damage being caused was not accelerating beyond what was projected to occur.

“We carefully inspect and trend the condition of the wheels,” said Steve Lee, Curiosity’s deputy project manager. “Cracks and punctures have been gradually accumulating at the pace we anticipated, based on testing we performed at JPL. Given our longevity projections, I am confident these wheels will get us to the destinations on Mount Sharp that have been in our plans since before landing.”

In particular, the mission team is watching for breaks or tears which damage the zig-zag treads – called grousers – on the 50cm / 20 in wheels. If three of these grousers are significantly broken, Earth-based tests suggest the damaged wheel will have reached about 60% of its serviceable life.

However, since Curiosity’s current odometry of 12.7 km (7.9 mi) is about 60 percent of the amount needed for reaching all the geological layers planned in advance as the mission’s science destinations, and no grousers have yet broken, the accumulating damage to wheels is not expected to prevent the rover from reaching those destinations on Mount Sharp.

“Naukluft Plateau” is a part of the larger “Stimson formation” which includes a fracture area the rover reached a late April. Dubbed “Lubango”, the area was the target for the rover’s 10th drilling and sample gathering campaign, which was completed on Sol 1320, April 23rd, 2016.

“We have a new drill hole on Mars!” reported Ken Herkenhoff, a MSL science team member, when reporting on the sample gathering in an MSL update on April 28th.

After transferring the cored sample to the CHIMRA instrument for sieving it, a portion of the less than 0.15 mm filtered material was successfully delivered this week to the CheMin miniaturized chemistry lab situated in the rover’s body, which is now analysing the sample and will return mineralogical data back to scientists on earth for interpretation.

“Lubango” was selected for sample gathering after it had been determined following examination using the ChemCam laser and spectrometer, that it was altered sandstone bedrock and had an unusually high silica content. To complement the analysis of “Lubango”, the science team has been using the rover’s camera systems to locate a suitable target of unaltered Stimson bedrock as the 11th drill target.

“The colour information provided by Mastcam is really helpful in distinguishing altered versus unaltered bedrock,” MSL science team member Lauren Edgar explained in describing the current work. One possible target, dubbed “Oshikati” has been identified.

The ChemCam laser has already shot at the “Oshikati” to gather data for an initial analysis of the rock and assess its suitability for drilling operations. If all goes according to plan, Curiosity should make an attempt to gather samples from the rock on Sunday, May 1st.

SpaceX To Launch NASA-Supported Mars Mission in 2018

On April 27th, SpaceX announced it plans to launch an automated mission to Mars in 2018 as a part of a new space act agreement the company has signed with NASA. This will see the US space agency provide technical support to SpaceX with respect to an automated landing of a SpaceX vehicle on Mars, and provide scientific support for the mission.

SpaceX will undertake the mission using Red Dragon, an automated version of the Dragon 2 capsule vehicle which will enter service in 2018 to fly crews two and from the International Space Station.

Red Dragon has been on the drawing boards at SpaceX almost since the inception of the Dragon 2 programme. Designed to be launched atop the upcoming Falcon 9 Heavy launcher, due to enter operations later this year, it is specifically intended to carry science payloads almost anywhere in the solar system, and could potentially deliver as much as 4 tonnes of cargo to the surface of Mars (that’s the equivalent of delivering 4.5 Curiosity rovers to Mars in one go).

The 2018 mission is primarily intended to look at using a purely propulsive means of achieving a soft landing of a heavy vehicle on Mars. While parachutes could, in theory, be used to help slow a vehicle’s descent through the Martian atmosphere, recent NASA tests of the kind of large-scale “supersonic” parachutes required to slow large space vehicles during their descent haven’t proved overly successful during comparable testing at high altitude on Earth.

Dragon 2 has been specifically designed so that a series of 8 rocket engines – called Super Draco motors – are embedded in the base of the vehicle. These can be used both as a launch abort system – firing a crew clear of a malfunctioning rocket during lift-off – and as a means of the vehicle achieving a “soft landing” on land rather than splashing down in the ocean (although the Dragon 2 is capable of this as well).

On Red Dragon, these super Draco motor allow the vehicle to slow itself down through its descent through the tenuous Martian atmosphere, and then act as a final cushioning break as the craft comes into land. Tethered tests here on Earth have already demonstrated Dragon 2 is fully capable of maintaining a hover until the thrust from the engines, and these tests will be expanded upon during the run-up to the mission.

The Red Dragon initiative is a commercial endeavour, funded entirely by SpaceX. NASA will not be contributing to the cost of the mission, but will be providing Earth-side logistical support and a suitable science payload of around 1 tonne. The exact nature of this payload will be defined in the future, but will likely include a diverse range of instruments which might be used to further characterise the Martian atmosphere, study and Martian weather and soil, and image the surface of Mars. Both SpaceX and NASA will share the data gathered during what is referred to as the EDL phase of the mission – the Entry, Descent and Landing. NASA will also supply a scientific payload for the flight.

Red Dragon marks the first phase of an ambitious programme SpaceX will be announcing in September, but which has been under development for about the last 6 years, for undertaking human missions to Mars in the 2020 / 2030s. I’ll have more on this later in the year.