Saturday, November 18th, 2023 saw SpaceX attempt the second flight test of the Starship / Super Heavy behemoth out of their Starbase Boca Chica facility near Brownsville, Texas, in what is called the Integrated Flight Test 2 (IFT-2), featuring Booster 9 and Ship 25.

Regulars to the column will likely remember that the first such test of this launch combination on April 20th (and then called Orbital Flight Test 1), didn’t go that well; the launch stack was totally lost four minutes into the ascent, whilst the 31 operating engines on the booster spent the 5+ seconds between ignition and launch excavating the ground under the launch stand (see: Space Sunday: Starship orbital flight test).

The failure of that flight came as no surprise: the vehicle wasn’t fit for purpose (by Elon Musk’s own admission), and the launch infrastructure, as many (myself included) was not fit for purposes as long as it lacked a sound suppression system / water deluge system. In this regard, the April 20th attempt – which was more about boosting Musk’s ego on the so-called “Elon Musk Day” than anything practical – proved us right, the booster’s engines excavating the ground under the launch stand and throwing enough debris into themselves as to cripple the flight before it even left the launch stand.

So, how did the second flight go? Well – spoiler alert – both vehicles were again lost; the booster within the first 3.5 minutes of flight and the Starship around 4.5 minutes later. However, even this allows the flight to be recorded as a qualified success in that it will have yielded a fair amount of usable data and it did potentially succeed in meeting its two critical milestones.

In all the flight might be summarised as:

- T -02:00:00 hours: fast sequence propellant loading commenced, pumping around 4,536 tonnes into the tanks of both vehicles, less than the 4,800 tonnes full load required for an orbital flight.

- T -00:00:05 seconds: the newly-installed and novel sound suppression system below the launch pad starts up, delivering a “cushion” of water under the launch stand in its first active launch test and the first critical milestone for the launch.

- T-00:00:00: ignition of Booster 9’s 33 Raptor engines.

- T +00:00:5 (approx 13:02:53 UTC): lift-off.

- T +00:00:10 the vehicle stack clears the tower.

- T +00:01:12 at 15km altitude and travelling at 1,500 km /h, the stack passes through Max Q, the period when it is exposed to the maximum dynamic pressure as it punches through the denser atmosphere.

- T +00:02:40 main engine cut-off (MECO) commences, with the raptors on Booster 9 shutting down sequentially from the outer ring of 20 and progressing inwards to leave just three running.

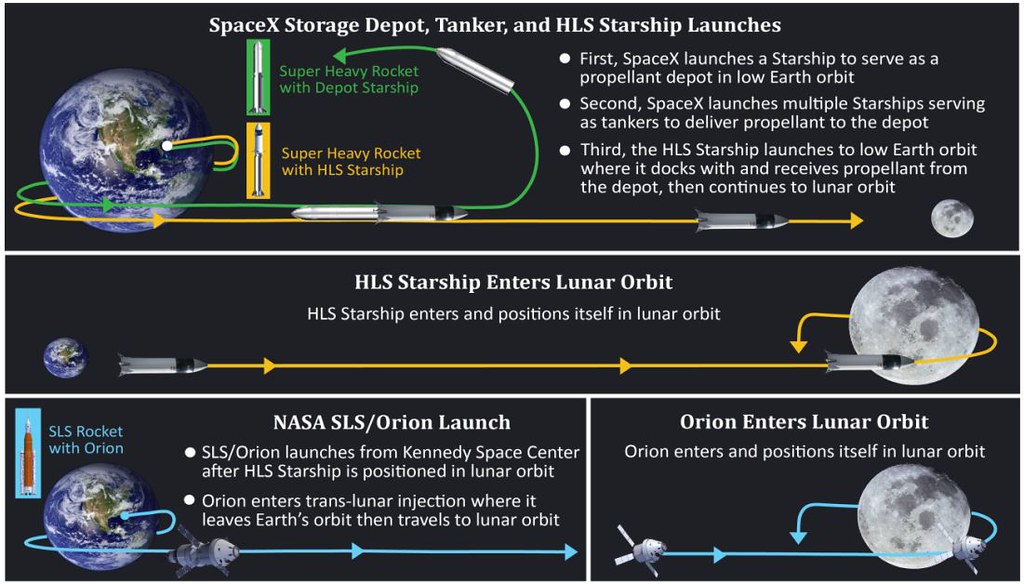

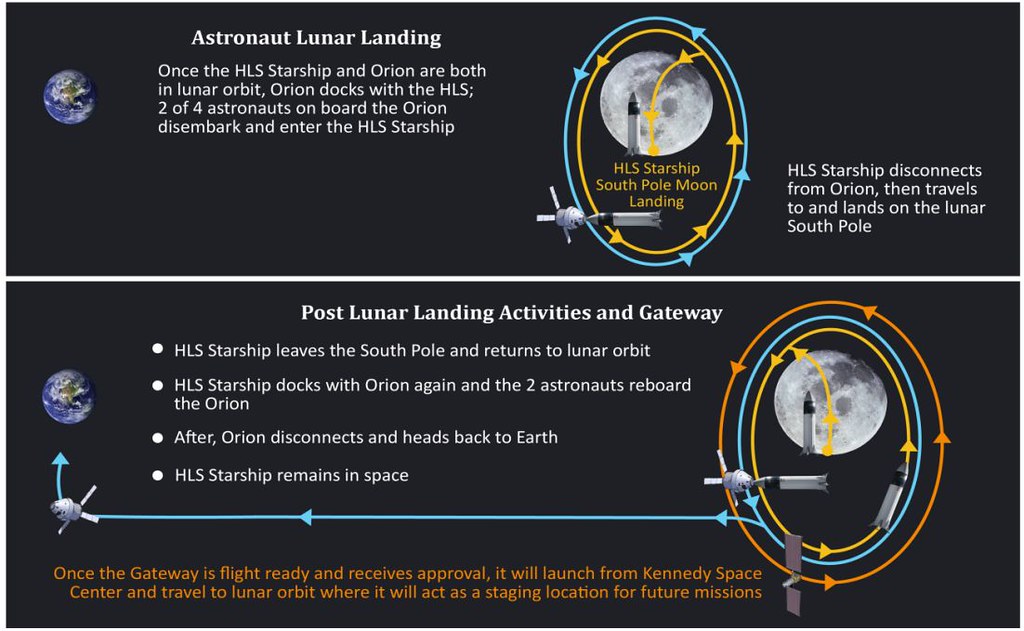

- T + 00:02:48: Ship 25 ignites its engines in a “hot staging” process – second critical milestone for the flight.

- T +00:02:49: Ship 25 separates from Booster 7, which fires upper and mid-point thrusters to tip itself away from Ship 25’s line of flight, using the thrust from its 3 remaining Raptor motors to increase its separation. Livestream graphic incorrectly shows 12 Raptors on the booster firing.

- T +00:02:57: Booster 9 uses its small thrusters to flip itself over (so the top of the booster is pointing back towards the launch facility) ready to commence a “boost back” burn. Graphic continues to show incorrect number of engines firing.

- T + 00:03:11: attempt to re-start the 10 motors of the inner ring to join the core 3 in firing for the “boost back” burn.

- T +00:03:15: one or two engines flare briefly, following by attitude thrusters firing to correct, or some form of propellant venting.

- T+00:03:17: further attempt at engine start-up, graphic now shows all 13 inner engines have shut down. Vehicle appears to be venting heavily from one side of the engine skirt.

- T +00:03:20: one or more engines appear to explode. A fraction of a second late, the midsection explodes and vehicle is destroyed.

- T +00:07:57: at an altitude between 140 and 148 km, and travelling at 23,350 km/h, Ship 25 appears to suffer an engine anomaly.

- T +00:08:04: all flight telemetry seizes, showing the vehicle travelling at a flat trajectory at 149 km altitude.

- T +00:08:08: Ship 25 is destroyed, – although mission control appear to be under the impression engine cut-off (scheduled for 8m 33s into the flight) had occurred prematurely and that the vehicle was still coasting in flight, publicly acknowledging it loss at 11m 23s after launch.

Many were quick to hail the test as a huge win for SpaceX; others were equally quick to call it a further failure. The truth actually lies somewhere in between, as I noted earlier.

On the one hand, the flight was a success in that it clearly demonstrated the hot staging concept works, and the new sound suppression system may well protect vehicle and launch facilities at lift-off; the flight was also sufficiently long enough for a lot of data to be gathered.

On the other, the ways in which Booster 9 and Ship 25 were lost indicating there is a lot still to be done. Those claiming this flight to have failed also point to the fact that Ship 25 never got to coast on a sub-orbital hop to re-enter the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean to splash-down near Hawaii.

However, while this was the supposed primary goal of April’s flight, for IFT-2, it was very much a tertiary objective; one a good distance behind hot staging and proving the sound suppression system. As such to call IFT-2 a failure based on this criteria is not entirely fair.

Of the two cited objectives, it is not unfair to say the jury is still out on the overall effectiveness of the sound suppression system. This is because – at the time of writing – we do not know its overall condition, as SpaceX has not released any post-launch images.

While there are various amateur videos of the launch stand and facilities post-flight, they are shot from a distance where it is impossible to judge the condition of the actual sound suppression system; therefore – and despite claims to the contrary made on their basis – we cannot tell how well it stood up to the blast from Booster 9’s engines.

All that can be positively determine from these videos is that the concrete on the launch stand withstood the blast considerably better than it did in April 2023, which show them to be in very good condition compared to the April 20th attempt, which might be indicative of the effectiveness of the sound suppression system – but that doesn’t mean it survived unscathed itself.

A further point here is that even if images do reveal the system to be relatively undamaged, that does not automatically mean it is fit for purpose; for one thing, this was an atypical launch: the stack was some 360 tonne lighter than it would be fully fuelled and with a payload – which likely reduced the degree of exposure the sound suppression system had to the fury of 33 Raptors operating at maximum thrust. Thus, it’s going to take a few more launches to really find out if the system is up to snuff or not.

Meanwhile, hot staging refers to igniting the motors of one stage of a rocket while it is still attached to a lower stage, rather than separating them first and then igniting the engine. When done right, it imparts an extra kick of velocity into the ascending stage which can be translated into a larger payload capability. Russia has been using hot staging in vehicles like Soyuz for decades, so the idea is not new; however, their rockets are built with it in mind; Super Heavy is effectively being retro-fitted with the capability, so there was a lot riding on this flight.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: Starship Integrated flight Test 2”