Previewed in my previous Space Sunday update, the FRAM2 mission lifted-off almost precisely on time from Kennedy Space Centre’s Launch Complex 39A at 01:46:50 UTC on April 1st, carrying the first humans to ever orbit the Earth in a low-Earth polar orbit.

The ascent to orbit, travelling south from the space centre, proceeded smoothly, the SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule and service module (“Trunk” in SpaceX parlance) entering a low Earth orbit with an apogee of 413 km and a perigee of 202 km some eight minutes after launch. The orbit, referred to as a polar retrograde, due to the fact the vehicle travelled first over the South Pole then around and over the North Pole, lay at an inclination of 90.01°, breaking the previous high inclination orbit record for a crewed space vehicle set by Vostok 6 in 1963.

Aboard the vehicle were Chinese-born, but Maltese citizen and crypto currency entrepreneur Chung Wang, who will be the mission’s commander and is a co-bankroller of the flight; Jannicke Mikkelsen, a Scottish-born Norwegian cinematographer and a pioneer of VR cinematography, 3D animation and augmented reality, who is the other co-bankroller for the flight; Eric Philips, a 62-year-old noted Australian polar explorer, who will be the first “fully” Australian national to fly in space, and Rabea Rogge, a German electrical engineer and robotic expert.

The 4-day mission comprised an extensive science programme, focusing on human health in space, growing food supplements on-orbit (oyster mushrooms) and investigating the Phenomena known as STEVE (see my last Space Sunday update) from orbit. The mission also included educational broadcasts to schools and a lot of social media-posted videos.

A video of Antarctica recorded by the FRAM2 crew. Seen in the footage is videographer Jannicke Mikkelsen, and the voice-over is from Eric Philips

To assist in observations and measurements, Resilience was fitted with the transparent Copula to replace the outer airlock hatch and docking mechanism within the forward end of the capsule, affording the crew near-360º views of Earth once the vehicle’s protective nose cone had been opened.

The launch itself required a complete update of the Crew Dragon navigation software, originally written for lower 51º inclination orbits. This included a complete overhaul of the launch abort software for both capsule and launch vehicle. The latter was made necessary by the fact the ascent to orbit carried the vehicle over parts of South America, so any abort situation had to ensure that both booster and capsule would not return to Earth over land, and the capsule would be able to splashdown safely with the crew.

What really marked this mission, however, was the sheer transparency of operations; nothing in the video logs was pre-scripted or rehearsed; camera were rolling with conversations going on in the background – including conversations between crew members and SpaceX mission control about “known issue” with the space vehicle (not sure how significant – but being told that there is a “known issue” with a vehicle when you’re sitting in it in space might not be the most comforting thing to hear!), informal chit-chat during observations and an introduction to the fifth “crew member”, Tyler.

A compilation video of the mission, including shot through the inner hatch of the airlock showing Earth beyond the Copula. Note the inner hatch could also be opened to allow crew to enter the forward are and look out of the Cupola

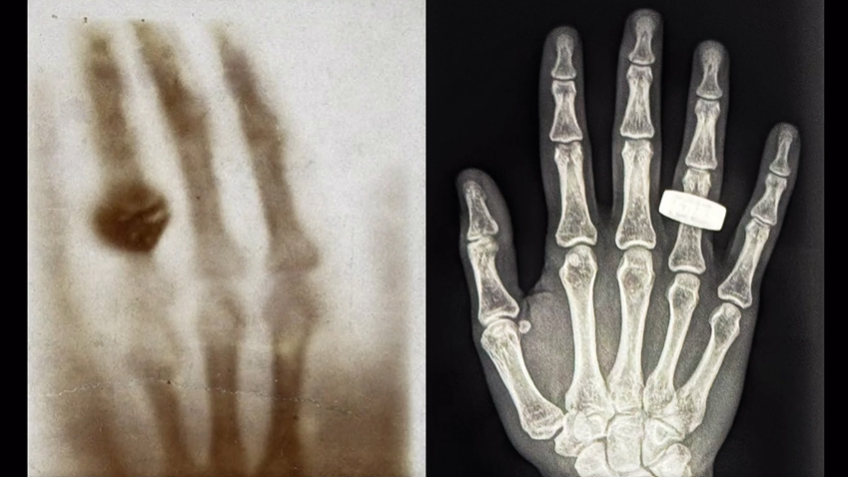

While the mission had a lot of science goals – including testing a portable MRI unit, carrying out x-rays of the human body, studies into blood and bone health and glucose regulation in the body in micro-gravity – it has not stopped criticism being levelled at it, with some scientists stating the period spent in space being too short to yield practical results in some areas, and other aspects of the mission being labelled “a notch above a gimmick”.

For Chung, Mikkelsen and Philips in particular, however, the mission was as much personal as scientific: they have spent fair portions of their adult lives exploring the Polar regions, carrying out studies and research (the four all actually met during an expedition to Svalbard (leading them to nickname the mission “Svalbard 1”).

FRAM2 came to an end on April 4th, 2025, when, following an extended de-orbit, the combined vehicle re-entered the atmosphere and headed for a splashdown off the California coast where the SpaceX recovery ship was waiting for the vehicle. This marked the first splashdown for Crew Dragon off the west coast of the USA – although more will be following.

SpaceX has been criticised for the fact that during several missions returning crews from the International Space Station, the “Trunk” service module has in part survived re-entry, with elements coming down very close to populated areas. To avoid this, the company is moving crewed splashdowns to the west coast of the USA in order to ensure that should any parts of the Trunk survive re-entry they will splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

As a test of this, the module used by Resilience remained attached to the vehicle for longer during the initial re-entry operations, in order to ensure that if any part of it did survive the heat of re-entry, the debris would fall to Earth over Point Nemo – the remotest part of the Pacific Ocean relative to human habitation, and referred to as the “spacecraft graveyard”.

Splashdown occurred at 19:28 UTC on April 4th, with the capsule and crew safely recovered to the SpaceX recovery vehicle for transport to the port of Los Angeles.

NASA Opens-Out Requirements for Private Missions to the ISS

NASA has announced it is seeking proposal for two further private astronaut missions (PAMs) to be conducted to the ISS – and for the first time, the requirement that such missions must be commanded by former NASA astronaut has been removed.

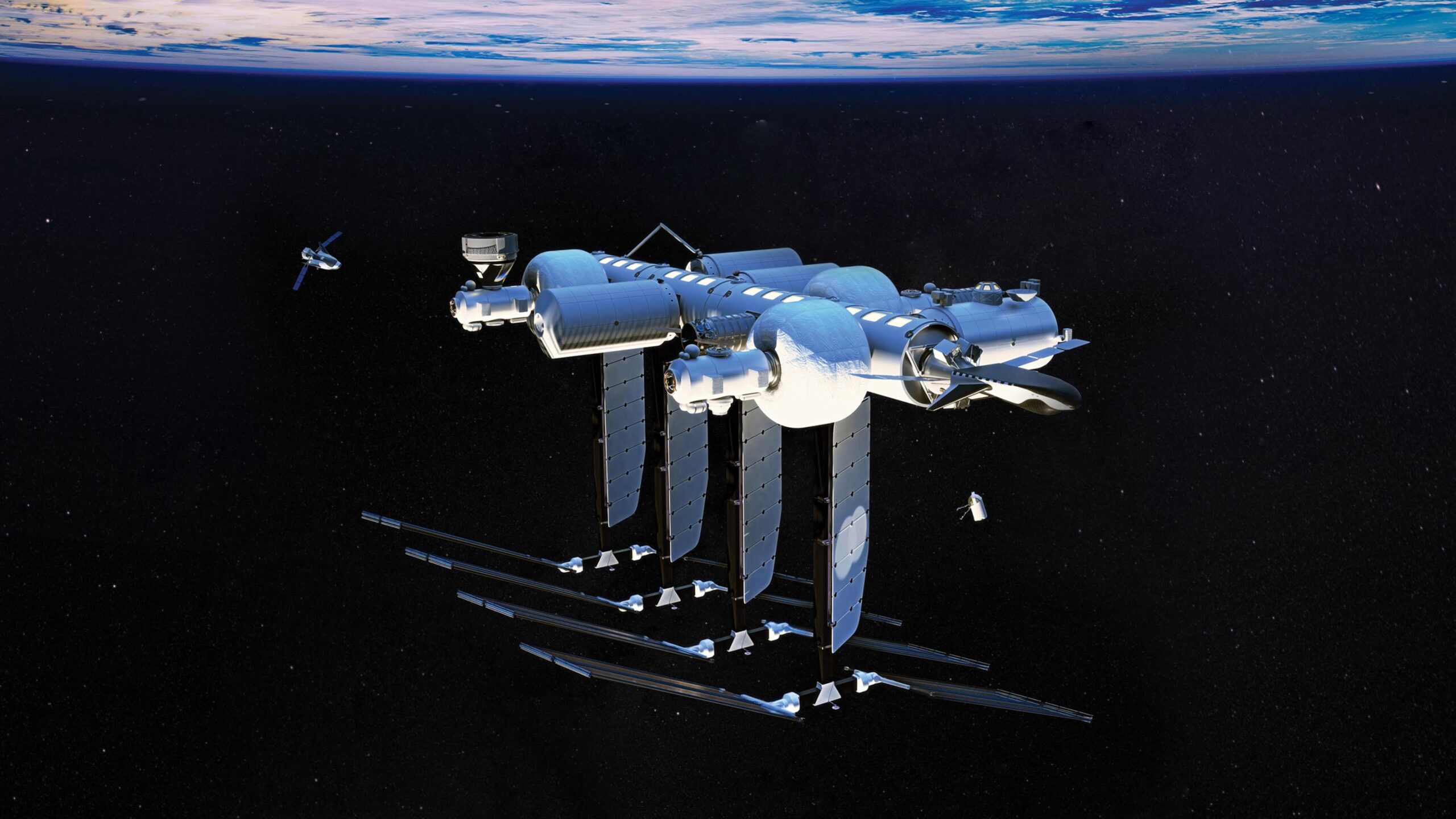

The agency is planning to pivot away from the International Space Station (ISS) operations as it nears its end-of-life (some of the Russian elements of the station are already well outside their “warranty” – that is, their intended lifespan), with the hope that the private sector will take over low-Earth orbit research and station operations. Currently, there are a number of proposals for doing so – perhaps most notably Axiom Space and the orbital Reef consortium led by Blue Origin and Sierra Space.

Axiom Space already has a contract with NASA to add its own modules to the ISS, starting in 2027 with the launch of the PPTM – Power, Propulsion and Transfer Module. This will then be joined by at least a second module, Hab-1, prior to the decommissioning of the ISS. These modules will then be detached from the ISS to become a free-floating hub to which Axiom will add further modules.

To prepare for this, Axiom signed an agreement with NASA to fly four missions to the ISS between 2022 and 2025, with the option on a fifth. Three of these form the only fully private missions yet flown to the ISS, and all have been commanded by former NASA astronauts – Michael López-Alegría (Axiom AX-1 and Ax-3) and Peggy Whitson (Ax-2), with Whitson also set to command AX-4, currently targeting a May 2025 launch.

Under the new NASA PAM requirements, private missions are now required to be commanded by any astronaut who has served as a long-duration ISS crewmember (defined as 30 days or more in the ISS) and who has been involved in ISS operations in the last five years or else shows evidence of “current, active participation in similar, relevant spaceflight operations”. This therefore opens the door for missions to be commanded by Canadian, French, German, English, Japanese, etc., astronauts meeting the requirements to command missions by commercial providers.

The move to relax the requirements is to help remove the reliance on purely NASA-based experience to lead private sector missions into orbit and allow companies like Axiom, Blue Origin and – most notably, perhaps – Vast Space, who have a MOU with SpaceX to fly two PAM missions to the ISS but have yet to meet NASA’s requirements to do so, to start formulating their own requirements, gain expertise and build partnership and processes to assist in their efforts to establish on-orbit facilities.

The announcement by NASA is of potential import to the UK: Axiom have an agreement in place with SpaceX to fly a total of five Ax missions to the ISS. However, the fifth – provisionally aiming for 2026 – has yet to be crewed, and there have been discussion between Axiom and UK officials about the mission being an “all British” crew, comprising Tim Peake as mission commander, who flew the Expedition 46/47 rotations on the ISS, together with fellow UK European Astronaut Corps members Meganne Christian, Rosemary Coogan and Paralympic sprinter (and surgeon) John McFall.

New Glenn Mishap Investigation Completed

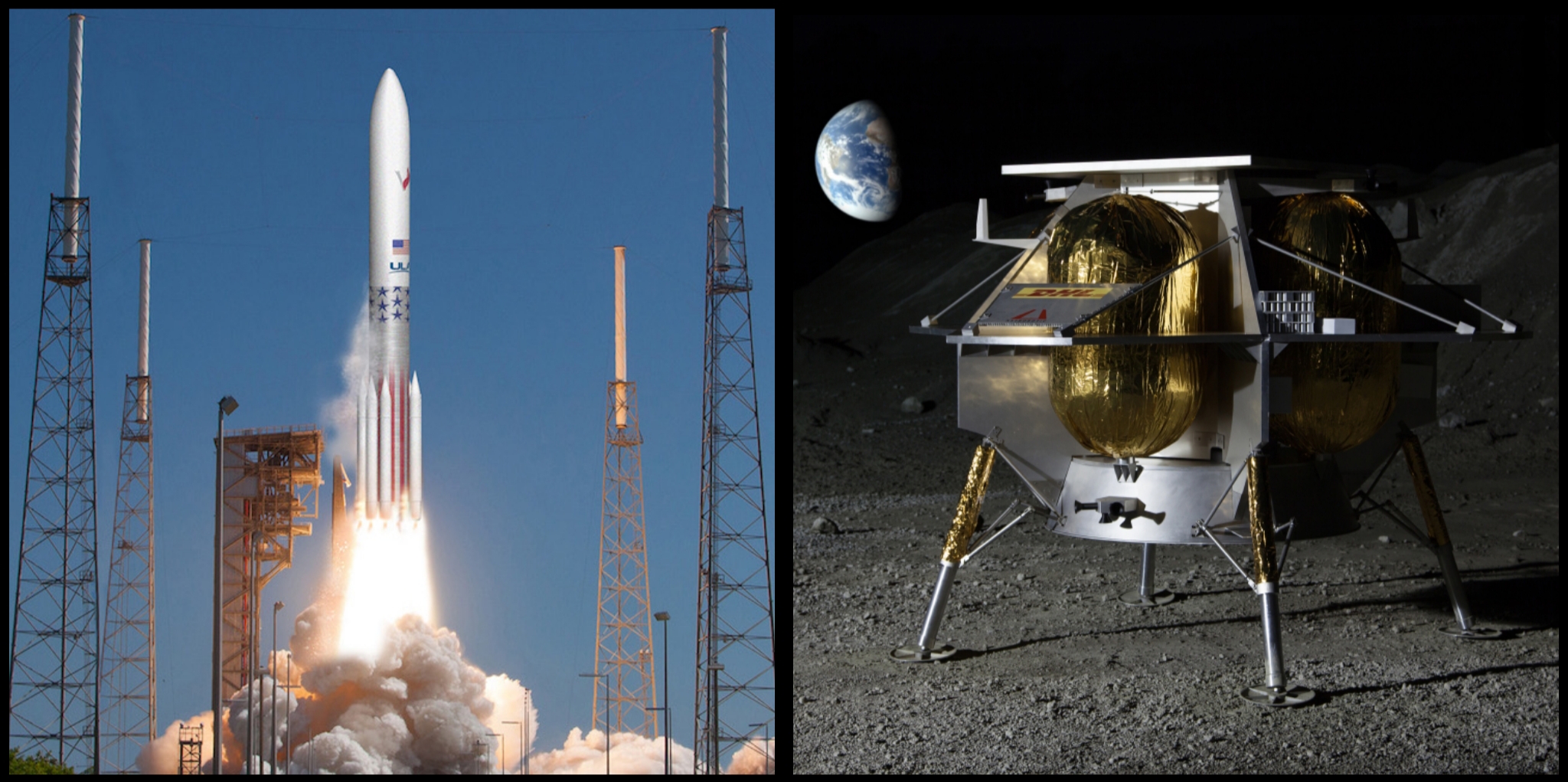

The Federal Aviation Administration announced March 31st, 2025 that it has accepted the findings of an investigation led by Blue Origin following the loss of the first stage of the company’s New Glenn heavy lift launch vehicle during its maiden flight on January 16th, 2025 (see: Space Sunday: NG-1 and IFT-7).

While the overall goals of that mission were met, a secondary goal – recovering the rocket’s large first stage by landing it at sea board a landing vessel – failed, the booster stage falling back into the Atlantic Ocean. Whilst no debris was strewn across flight corridors or fell on populated areas (unlike recent SpaceX Starship launch attempts), the failure of the planned booster recovery, whilst always rated by Blue Origin as having a minimal chance of success on the very first flight of the rocket, meant the vehicle’s launch license was correctly suspended by the Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) until a full Mishap Investigation into the cause of the loss had been carried out by Blue Origin and the FAA had accepted the findings and remedial actions taken.

The investigation report was duly supplied in March 2025, and identified the booster’s inability to re-ignite its motors during descent as the cause of the loss. Whilst no precise cause(s) for this failure have been openly published, Blue Origin has indicated seven areas where remedial work has been undertaken on the vehicle’s flight systems, and the FAA now consider the investigation closed. As a result – subject to a final inspection of the changes made – the license suspension should be lifted before the end of April. In the meantime, Blue Origin has been given the all-clear to resume preparations for the next New Glenn launch.

All of this is in stark contrast to the handling of the last two SpaceX Starship launches (IFT-7 and IFT-8). Both resulted in the complete loss of the Starship upper stages well within Earth’s atmosphere, resulting in debris falling over the Greater Antilles (and some of it striking close to populated areas on the Turks and Caicos islands) together with a degree of disruption to commercial flights in the region. However, in the case of IFT-7, the FAA cleared the launch of IFT-8 before the Mishap Investigation was closed, and appears to be on course to do so in the case of IFT-8, with SpaceX already ramping-up for the next test article flight.

In the meantime, assuming the New Glenn license is renewed in April, the next launch for the vehicle could come as soon as “late spring 2025” (end of May). However, no payload for the flight has been specified, only that it will include a further attempt to return the first stage to an at-sea landing aboard Landing Platform Vessel 1 Jacklyn.

Some reports had suggested this next launch could comprise the Blue Moon Mark 1 lander – an automated vehicle capable of delivering up to 3 tonnes of payload to the surface of the Moon and intended to demonstrate / test technologies to be used in the company’s much larger Blue Moon Mark 2 lander, designed to deliver crews to the surface of the Moon. However, in discussing the launch path for New Glenn, Blue Origin CEO David Limp indicated that a launch of Blue Moon Mark 1 is unlikely to occur before late summer 2025 at the earliest.

2024 YR4 Seen At Last

As I noted in February 2025, 2024 YR4 is an Earth-crossing Apollo-type asteroid discovered on December 27th, 2024. It caused a bit of stir at the time, as there was a non-zero chance that as it pursued its own orbit around the Sun, in 2032 it could end up trying to occupy the space volume of space as taken-up by or own planet, with potentially disastrous and deadly results for anyone and anything caught directly under / within the air blast that would likely result from its destruction as it tore into our atmosphere.

Fortunately, continued observations of the asteroid – which passes across Earth’s orbit roughly once every 4 years – have shown the threat of any impact in 2032 are now very close to zero (although it does still exist on the tiniest of scales, together with a smaller chance of it hitting the Moon).

At the time of its discovery, 2024 YR4 was classified as a stony S-type or L-type asteroid, somewhere in the region of 50-60 metres across (roughly the same size as the fragment which caused the 1908 Tunguska event). That size estimate has now been confirmed, and what’s more, we now have our first (and admittedly fuzzy) images of the fragment, courtesy of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and they reveal it to be a strange little bugger.

Imaged and scanned by the US Near-InfraRed Camera (NIRCam) and British-led European Mid-InfraRed Instrument (MIRI), 2024 YR4 is indeed some 60 metres across at its widest. It is also somewhat unlike similar asteroids in its spectral type, in that it has a high spin rate as it tumbles around the Sun and appears to be more a conglomeration rocks banded together, rather than a single chunk of rock.

Observations are continuing to ensure the 2032 rick of impact is completely eliminated and also to provide data to calculate impact risks beyond 2032, whilst the data obtained by JWST – which mark 2024 YR4 as the smallest object the observatory has every imaged from its L2 HALO orbit – are being used to help scientists to better characterise NEOs of a similar size and spectral type and more fully understand how they might react were one to strike our atmosphere.