Clouds are rare on Mars, but they can form, being typically found at the planet’s equator in the coldest time of year, when Mars is the farthest from the Sun in its oval-shaped orbit. However, in 2019 – a year ago in Martian terms – the Mars Science Laboratory team managing NASA’s Curiosity rover in Gale Crater noticed the clouds there forming earlier than expected.

With the onset of winter in the region earlier in 2021, the MSL team wanted to be ready in case the same thing happened, training the rovers cameras on the sky around “Mount Sharp” to catch any evening cloud formations that might appear as the tenuous atmosphere cooled towards night-time temperatures.

What resulted are images of wispy puffs filled with ice crystals that scattered light from the setting Sun, some of them shimmering with colour. Visible through both the black-and-white lenses of the rover’s navigation cameras and the high-resolution lenses of the Mastcam system, the pictures captured by Curiosity might easily be mistaken for high-altitude clouds here on Earth.

And high altitude is precisely the term to use for this clouds. Most clouds on Mars largely comprise water vapour and water ice. They tend to occur some 60 km above the planet, although they can occur much lower – the massive shield volcano of Olympus Mons, for example, has oft been images with cloud formations around its flanks, the product of differing atmospheric temperature regimes on the slopes.

However, the clouds seen by Curiosity are believed to be far higher than 60 km in the Martian atmosphere, and are thought to be largely composed of frozen carbon dioxide (dry ice). They occur during the twilight hours – although the mechanism that gives rise to them is not fully understood; but they are thin enough for sunlight to pass through them, catching the ice crystals and causing them to shimmer for a time before the Sun drops below their altitude, causing them to darken. This effect gives them their name: noctilucent (“night shining”) clouds.

These clouds are best seen in the black and white images captured by the rover’s Navcams, as shown here. However, there is a second form of clouds best seen via Curiosity’s Mastcam colour images. These are iridescent, or “mother of pearl” clouds, rich in pastel colours.

They are the result of the cloud particles all being nearly identical in size, something that tends to happen just after the clouds have formed and have grown at the same rate. The colours are so clear, were you able to stand on Mars and look at the clouds, you’d see the shades with your naked eye, and they are another part of the beauty of Mars.

Ingenuity Hiccups During Sixth Flight

NASA’s Mars helicopter Ingenuity encountered some trouble on its sixth flight – the first flight of its extended mission – on May 22nd.

The flight should have seen the helicopter climb to a height of 10 metres, then fly some 150 metres south-west of its starting point to reach a point of interest where it would travel south for 15 metres, imaging the terrain around and below it for study by scientists on Earth, before making a return to a point close to where it lifted-off.

The flight was designed to be the first specifically targeted at testing the helicopter’s ability to be used in support of ground operations on Mars, offering the mission team the chance to determine if the area images might be worth a future foray by the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover.

However, 54 seconds into the flight, Ingenuity suffered a glitch that interrupted the flow of images from its navigation camera to its onboard computer. This meant that each time the navigation algorithm performed a correction based on a navigation image, it was operating on the basis of incorrect information about when the image was taken, leading to incorrect assumptions about where it was and what it should be doing.

This lead to Ingenuity pitching and rolling more than 20 degrees at some points during the flight as it struggled to return to its landing zone, post-flight telemetry revealed the helicopter experienced some significant power consumption spikes. However, it maintained its flight and executed a safe landing just 5 metres from the intended touch-down point.

In a very real sense, Ingenuity muscled through the situation, and while the flight uncovered a timing vulnerability that will now have to be addressed, it also confirmed the robustness of the system in multiple ways. While we did not intentionally plan such a stressful flight, NASA now has flight data probing the outer reaches of the helicopter’s performance envelope That data will be carefully analysed in the time ahead, expanding our reservoir of knowledge about flying helicopters on Mars.

Håvard Grip, Ingenuity’s chief pilot.

Making the Moon a Busy Place

It’s starting to look like the Moon is going to be a terribly busy place. NASA’s Artemis programme is gathering pace in several areas – despite a degree of in-fighting among the principal US contractors – Russia and China have signed an accord that is liable to see them operating in the lunar south pole regions alongside the US-led mission (although the two will remain separate mission entities), whilst Canada and Japan have announced missions to the Moon as a part of the overall Artemis framework, and NASA is seeking ideas from lunar rover vehicles.

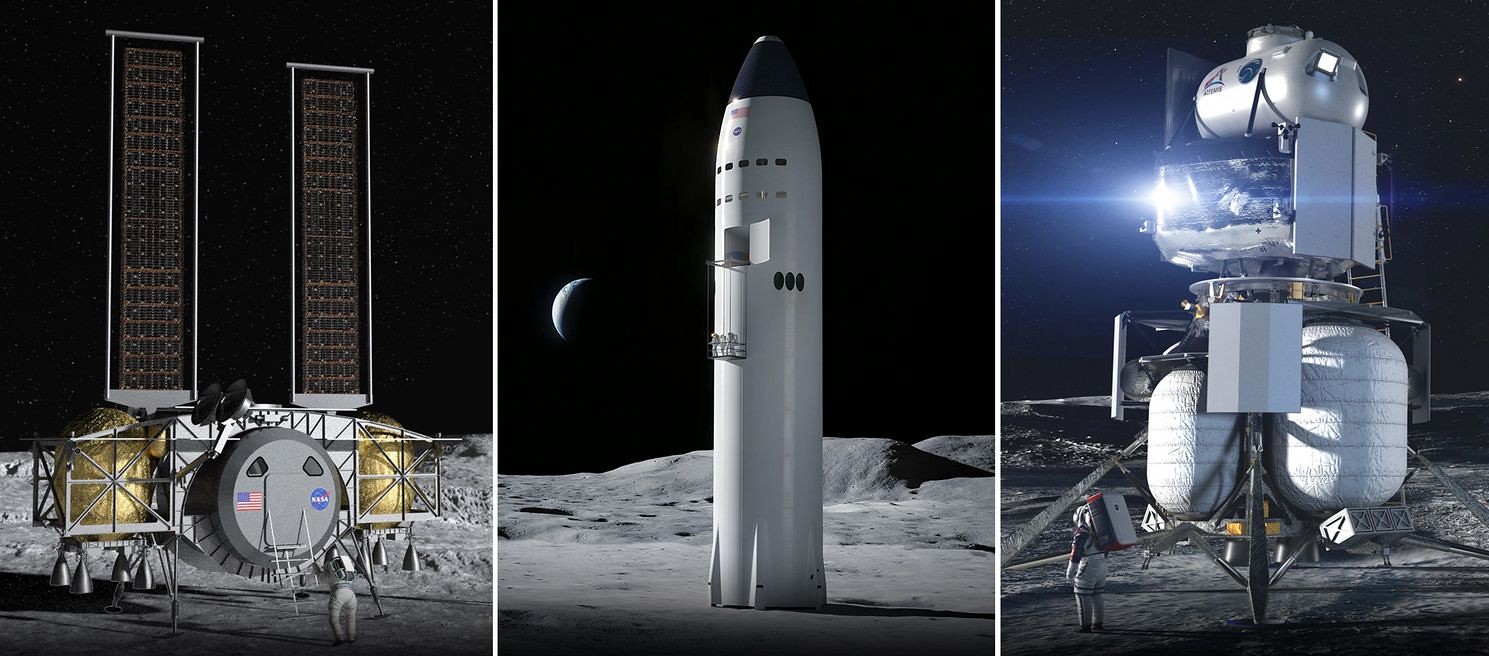

The in-fighting revolves around NASA’s April announcement that SpaceX will be granted a sole contract to develop the HLS – Human Landing System – the vehicle that will place humans on the surface of the Moon and return them to orbit. It was a contentious decision; the US agency had previously indicated that two contracts for HLS would be granted, with three players involved: a team led by Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin, a team led by Dynetics, and the late-comer to the party, SpaceX.

There were several leading reasons for the decision – including the matter of cost. However, both Dynetics (potentially with the most flexible approach to HLS) and Blue Origin raised objections with the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which ordered NASA to cease any financial support to SpaceX (worth a total of US $2.9 billion) to the SpaceX effort until it has completed an investigation.

The US Senate has also weighed-in on the subject, with Senator Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.), chair of the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee, adding an amendment to the Endless Frontier Act which forms the backbone for financing the Artemis programme, requiring NASA put a further US $10 billion into HLS – whilst Senator Bernie Sanders (D-Vermont) went the other way by calling for the cancellation of the entire HLS programme, wrongly characterising it as the “Bezos Bailout”, and so doing what he does best; creating further division and confusion.

As it is, the GAO will release its findings on the matter in August, and while it is hard to ascertain the impact of the delay, it would likely further diminish NASA’s chances of achieving the original goal of a return to the Moon by the end of 2024.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: Martian clouds, lunar missions and a space station”