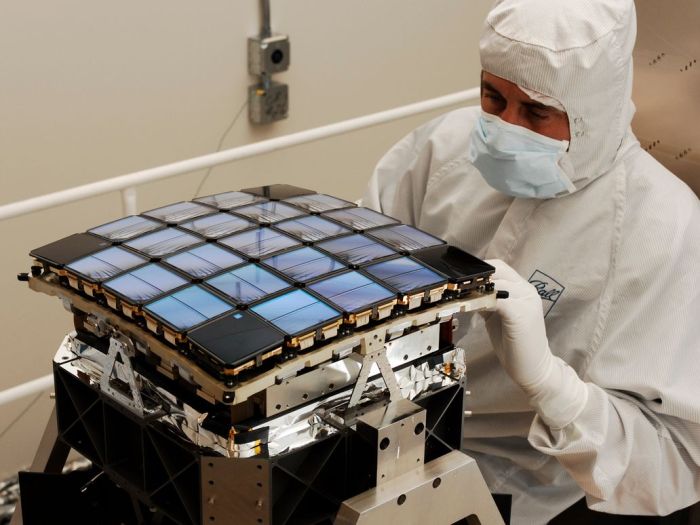

Last week I reported on the latest issue to strike NASA’s Kepler mission to survey other stars for signs of planets orbiting them. On July 28th, during routine communications with the observatory – which is following the Earth around the Sun roughly 121 million kilometres (75 million miles) “behind” the planet – it was discovered the photometer, the camera-like tool used to detect alien planets, had been turned off.

Power was restored to the unit on August 1st, but engineers were still mystified as to why it had turned off in the first place. Communications with the observatory on Thursday, August 11th, confirmed the photometer was still active and Kepler was gathering data, allowing the engineering team to focus on a possible cause for the unit powering off.

The Photometer includes a curved focal plane of 42 charge-coupled devices (CCDs) arranged within 25 individual modules. One of these modules – Module #7 – suffered a power overload in January 2014, disabling it. Most crucially, the failure prompted the photometer unit to power itself off – just as appeared to have happened shortly before July 28th, 2016, suggesting the most recent issue could also be related to the focal plane.

Analysis of the data received following the restoration of power to the photometer reveals that another module, Module #4, had failed to warm up to the required operating temperature, strongly suggesting it has also failed, and thus triggered the power-down.

As a result, the science and engineering team responsible for the mission have determined that the targets that were assigned to Module #4 will yield no further science results, but this should not impact Kepler’s overall science campaign, which is expected to continue through until 2019, by which time all no-board fuel reserves will have been depleted, and much of Kepler’s work will have been taken over by the James Webb Space Telescope and NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), examined in my previous Space Sunday column.

An “Earth-Type” World Just 4.2 Light Years Away?

Kepler has detected over 4,000 exoplanet candidates, of which around 216 have been shown to be both roughly terrestrial in size and form, and located within the “Goldilocks Zone” (or more formally the circumstellar habitable zone (CHZ) or habitable zone) around their parent star – the region at which planetary conditions could be “just right” for life to arise. Unfortunately, most of these planets are a very long way away. Kepler 425b, for example, regarded as Earth’s (slightly bigger) “cousin”, and the first exoplanet to be confirmed to be orbiting in its star’s habitable zone, is some 1,400 light years away.

However, Kepler is not alone in the hunt for extra-solar planets. Observatories here on Earth are also engaged in the work, both in support of Kepler by undertaking detailed follow-up examinations of candidate stars, and also as part of their own programmes. A recent article in Germany’s Der Spiegel magazine now claims that one of these, the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) La Silla faclity, has found an “Earth-like” planet very much closer to home.

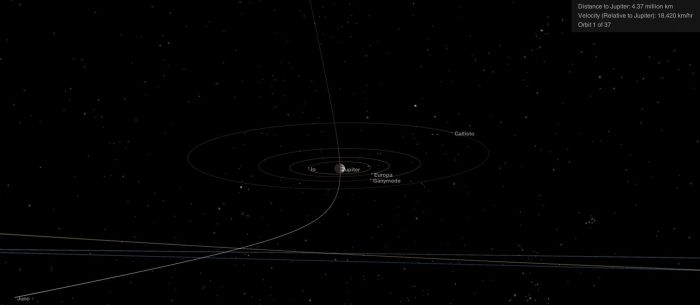

Quoting an alleged member of the ESO team, Der Spiegel states the new planet is orbiting Proxima Centauri, our nearest stellar neighbour, a mere 4.25 light years away, and which can be seen in the southern hemisphere night skies. A red dwarf low-mass star roughly one-seventh the diameter of our Sun, or just 1.5 times bigger than Jupiter, it is thought to be gravitationally bound to the Alpha Centauri binary system of stars, frequently the subject of science-fiction stories down through the decades.

Given the two primary stars in the Alpha Centauri system are broadly similar to our own Sun – Alpha Centauri A particularly so – and both are slightly older (around 4.85 billion years), the system has been a frequent subject for study, with the potential for either star to have planetary bodies orbiting it, or given the two stars orbit one another every 79.91 terrestrial years at a distance roughly equivalent to that between the Sun and Uranus, quite possibly around both of them. In fact, two recent papers have suggested two planets orbiting Alpha Centauri B. The first, from 2012, was subsequently dismissed as a spurious data artefact. The second, from 2015, has yet to be confirmed.

So far, ESO representatives have refused to confirm or deny the Der Spiegel article, or whether an announcement on the matter will be made at the end of August as the magazine claims. This has been taken by some as tacit confirmation of the discovery, and others that the data – if true – is still being verified. If the latter is the case, some caution at ESO is understandable: the La Silla Observatory was responsible for announcing the 2012 discovery of “Alpha Centauri Bb”, which as noted above, turned out to be a data anomaly.

Some are outright sceptical of the article, pointing out that Proxima Centauri has long been the subject of exoplanet searches by both observatories on Earth and the Hubble Space Telescope, and nary a hint of another other body, large or small, orbiting it has been found.

As a dwarf star – one of the smallest known – Proxima Centauri is also somewhat volatile, with about 88% of the surface active (far more than the Sun’s), and is completely convective, giving rise to massive stellar flares. While this doesn’t out the potential for planets to be orbiting it, the fact that the star’s habitable zone is between 3.5 and 8 million kilometres from its surface, any planet within that zone would be tidally locked to Proxima Centauri, leaving one side in perpetual daylight and the other in perpetual night, with the risk that any atmosphere would be stripped away over the aeons by the stellar flares. So even if the Der Spiegel article is confirmed, it would seem the planet might still be a pretty inhospitable place, even if it is within the Goldilocks zone.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: exoplanets, greenhouses and meteors”