NASA’s Mars 2020 rover Perseverance reached a milestone in its exploration of the region that includes Jezero Crater, when it was confirmed on December 12th, 2024 that the rover had reached the top of the Crater’s rim, and is now in a position to commence exploration along the edge of the crater as it starts a new science campaign.

For the majority of its time on Mars, Perseverance has been exploring within the crater, looking for evidence of the planet’s potential to have once harboured life and investigating the geological history of the crater itself, which was once home to liquid water. These investigations have comprised four science campaigns thus far:

- Crater Floor: the first campaign following the rover’s arrival on Mars in February 2021, through to the end of March 2022, as it exploring the floor of the crater and investigated sites of geological interest, making its way towards the outflow delta of a river which once tumbled into the crater.

- Fan Front: running from April 2022 through March(ish) 2023, this involved explorations of the lower end of the delta’s outflow plain, traversing a transitional region rich in evidence of water having once been free-flowing and comprising rock and material deposited in the crater rather than forming it.

- Upper Fan: This saw the rover reach the upper limits of the delta fan, where time was spent in further studies which included potential routes up the crater wall, possibly using one of the former river channels, and then starting its initial ascent.

- Margin Unit: starting in September 2023, this saw the rover enter a “marginal zone”, or lithological boundary between the lower slopes of the crater and its upper walls, and a region of intense geological study.

Following some 8.5 months of study whilst traversing upwards as part of the Margin Unit campaign, in August the focus switched to the rover just getting up the rest of the “Mandu Wall” and up and over the crater’s rim, using a combination of Earth-based route planning and “driving”, and allowing the rover to steer its own course through hazards and difficult areas using its autonomous driving capabilities.

The rover finally reached the crater rim on December 5th, 2024, where it paused on a rise at the rim the mission team dubbed “lookout hill”, allowing the rover to catch its breath and take a look at its surroundings – and the mission team to identify possible points of exploration as they confirm plans for the next science campaign, which has been dubbed “Northern Rim”.

This is a slightly confusing name given Perseverance has ascended the south-western side Jezero’s rim, but can be explained by the fact it has arrived at the northern end of that part of the rim. It’s a location the mission has long hoped to reach, because it forms a region of significant scientific interest.

The Northern Rim campaign brings us completely new scientific riches as Perseverance roves into fundamentally new geology. It marks our transition from rocks that partially filled Jezero Crater when it was formed by a massive impact about 3.9 billion years ago to rocks from deep down inside Mars that were thrown upward to form the crater rim after impact. These rocks represent pieces of early Martian crust and are among the oldest rocks found anywhere in the solar system. Investigating them could help us understand what Mars — and our own planet — may have looked like in the beginning.

– Ken Farley, Mars 2020 mission project scientist, JPL

The first point of interest due for in-depth study as a part of the Northern Rim campaign is a mound outside of the crater dubbed “Witch Hazel Hill”. Standing on the outside of the crater’s rim, the mound is around 100m tall, and comprises layered materials that likely date from a time when Mars had a very different climate than today; thus as it will be able to gather “snapshots” of the ancient geological history of Mars going back potentially billions of years.

From here, the rover is expected to make its way to “Lac de Charmes”, a region roughly 3.2 km from the crater rim, and believed to have not been greatly affected by the crater’s impact formation and thus likely to reveal more about the composition of the ancient crust of Mars.

Once the studies of “Lac de Charmes” have been completely, Perseverance is expected to make its way back towards the crater rim to a location dubbed “Singing Canyon”. Here it will examine megabreccia, or huge blocks of bedrock thought to have been hurled clear of the impact zone which gave rise to the 1,900 km wide depression of Isidis Planitia, on the edge of which Jezero Crater sits. The basin of Isidis forms the third largest impact structure on Mars, and was created some 3.9 billion years ago when an object estimated to be some 200 km across slammed into Mars.

This impact occurred during the Noachian Period on Mars, the epoch which saw free-flowing water on the planet and the time when the great volcanoes of the Tharsis Bulge are thought to have formed. Thus, the study of the megabreccia could unlock insights into how the Isidis impact many have both reshaped the surface of Mars, affecting things like the outflow of water and the general atmospheric environment, and so potentially impacted conditions suitable for the evolution of life on the planet.

The journeys to (and down) “Witch Hazel Hill” and then back to the crater rim via “Lac de Charmes” is likely to take Perseverance around a year to complete, during which time it will cover some 6.4 km in total, with four points of geologic interests thus far identified for scientific study as it does so. As the new science campaign opens, the mission tam also hope it will see the rover encounter much improved driving conditions when compared to the climb out and out of the crater.

Ingenuity Crash Investigation

One aspect of the Mars 2020 which will continue to be missed is that of Perseverance’s airborne companion, the little helicopter drone – and first powered vehicle from Earth to fly in the atmosphere of another world – Ingenuity.

As I reported at the start of the year (Space Sunday: a helicopter that could; a lander on its head) the helicopter, which had been designed with just 5 flights in mind but went on to make a total of 72, becoming an invaluable aid in scouting potential routes of exploration for the Mar 2020 rover, was “grounded” and “retired” at the start of 2024, following a mishap at the end of its 72nd flight on January 18th, 2024.

Images taken of the grounded drone and its surroundings later revealed not only had one or more of its rotor tips been broken (as revealed by Ingenuity taking pictures of its own shadow a few days after the incident), it had completely shed an blade.

Since the accident, NASA personnel at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory have been carrying a long-distance investigation into what may have caused the accident that resulted in Ingenuity’s effect loss. At the time of the mishap, Ingenuity was involved in efforts to help Perseverance navigate the upper slopes of Jezero Crater’s rim, which was proving difficult In particular the little helicopter was overflying a field of sand dunes in the hope of finding a route by which Perseverance could traverse them safely. However the lack of clearly definable surface features within the dune field was affecting Ingenuity’s ability to navigate / maintain its correct velocity.

To explain: in order to maintain both its horizontal and vertical velocity within safe parameters when descending, Ingenuity uses a downward-pointing camera to track surface features.: boulders, rocks, shadows, etc. However, the dune field it was overflying was almost uniformly bland and without significant features. This had already proven to be an issue on the helicopter’s 71st flight, when what appears to have been a light brush with the sand of a dune on landing caused a very slight deformation in one root.

Ironically, it as because of this incident that the mission team slotted-in the 72nd flight: they wanted to test Ingenuity’s capabilities to see if their were any abnormalities in flying as a result of the deformation. As such, it was intended to be a straight-up, hover, traverse a short distance a and flight, they kind performed multiple times in the past. So what went wrong?

Following extensive study of high-resolution images gathered by Perseverance of the damaged helicopter in February 2024, together with a careful review of data from the flight and images recorded by Ingenuity whilst flying, the JPL investigators and engineers from AeroVironment, who built the drone for NASA/JPL, now conclude Ingenuity suffered a similar issue as the 71st flight: it simply could not discern surface details via the navigation camera that could help it properly verify its vertical and horizontal motion.

As a result, investigators believe that Ingenuity approached the ground at the end of the planned20-second flight with a high horizontal velocity, resulting in a hard impact with the back slope of a sand ripple. The force of the impact, coupled with the slope, was enough to pitch the helicopter sideways and roll it forward. However, rather than bringing the blades in contact with the ground as had been thought, the combination of pitch and roll overstressed all four blades at a point of structural weakness roughly one-third of the way back from their tips, snapping them. This instantly caused both severe rotor vibration and imbalance, causing the mounting for one blade to fail completely, with the remnant of the blade hurled some 15 metres from the landing point.

This act additionally caused a power surge, which in turn caused the loss of communications at the end of the flight as the helicopter temporarily placed itself in a safe mode to protect its electronics.

Whilst it has remained unable to fly, Ingenuity has been far from silent in the months since its January 2024 accident: elements of its electronics – some of which are off-the-shelf components used in cell phones and table devices – are still operational, enabling it to continue to monitor the atmosphere and environment at its crash site and send that data on a roughly weekly basis to Perseverance for onward transmission to Earth.

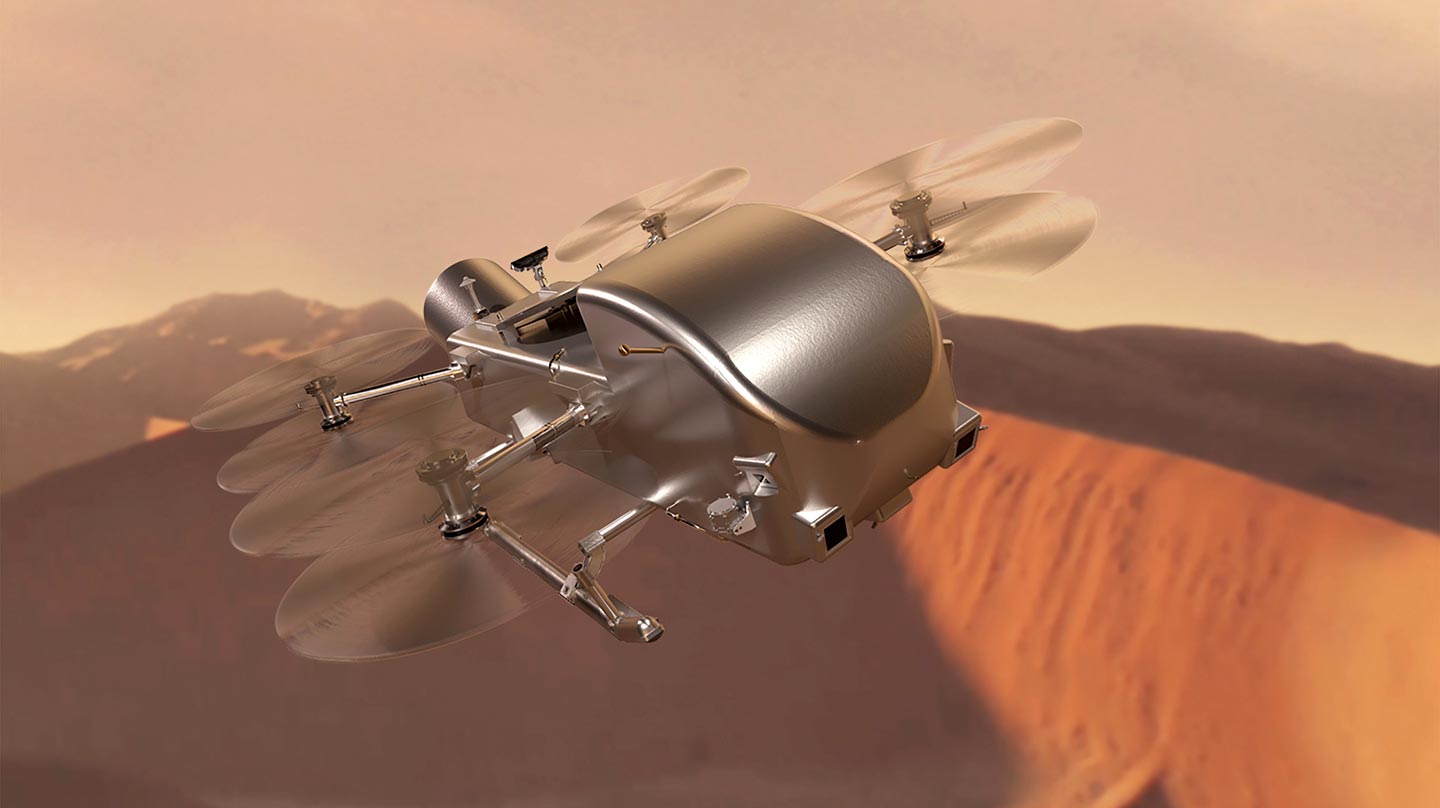

In addition, all of the data gathered from Ingenuity is being used to directly inform the design and capabilities of the next generation helicopter JPL hopes to build with AeroVironment. This is a more complex vehicle which perhaps more closely resembles rotary drones as used here than was the case with Ingenuity. Comprising a central body with (as currently envisaged) six electrical motors each powering a four-bladed rotor, the craft has been dubbed the Mars Science Helicopter (MSH) or simply “Mars Chopper”.

A key aim of the MSH project is to develop a craft capable of deploying and recovering science packages between 0.5 and 2.0 kg mass as it autonomously explores Mars.