I’ve covered the US-led Project Artemis quite a lot in recent Space Sunday pieces, largely as a result of all the speculation about NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) and Orion vehicle facing potential cancellation (for the tl;dr folk, whilst SLS is perceived as being “too expensive” the practicalities are that, like it or not, there is no launch capability available which could be easily “slotted-in” to Artemis to replace it any time soon). However, another reason for doing so, is the support work and missions related to Artemis are busily ramping up.

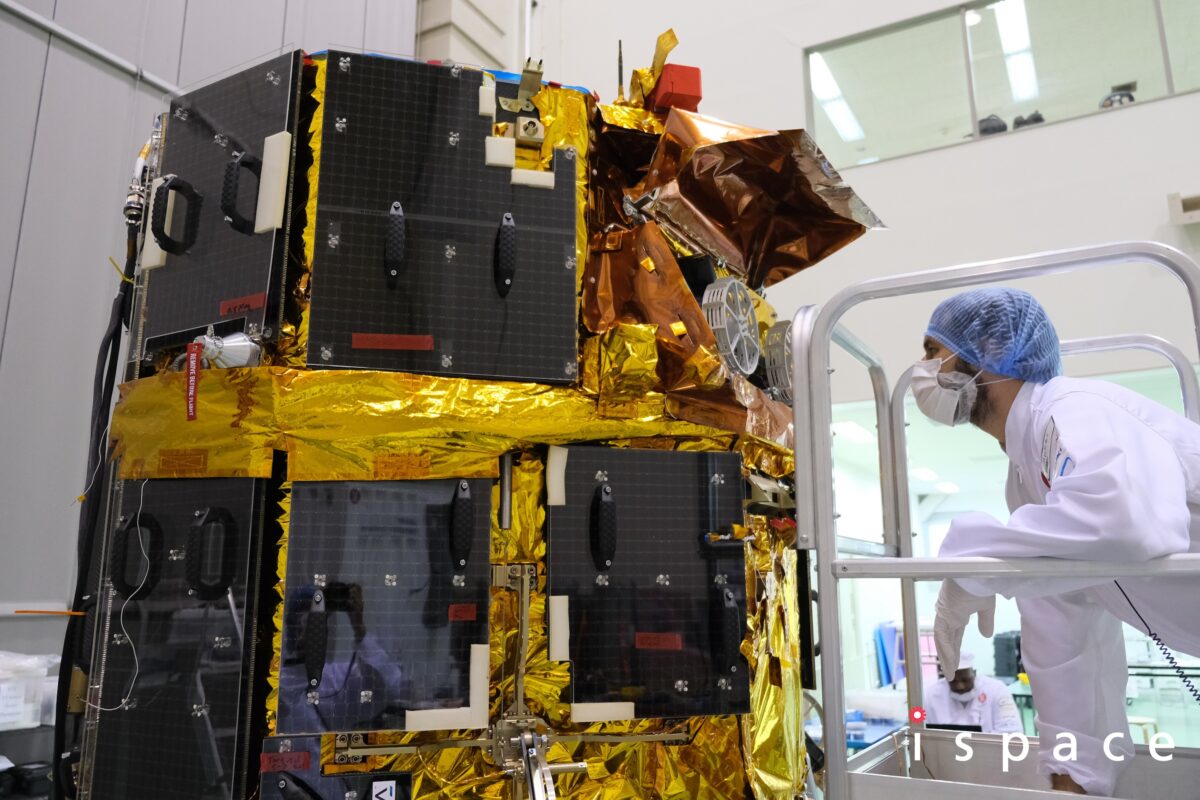

Back in January, Firefly Aerospace saw the launch of their Blue Ghost lunar lander on a shared ride to the Moon atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, its companion being the Japanese private-venture Hakuto-R Mission 2 lander Resilience. Whilst built and operated by Firefly Aerospace, Blue Ghost Mission 1 – which also has the mission title Ghost Riders in the Sky, named for the 1948 song of the same name – has been developed under NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, and thus has the official NASA designation (just to confuse things further) of CLPS TO 19D.

After a gentle cruise out to the Moon by steadily increasing its orbit distance from Earth until it could transfer to a distant lunar orbit and then slowly close on the Moon from there – thus requiring minimal propellant payload – the Blue Ghost vehicle touched-down on the Moon on March 2nd, 2025, becoming the first commercial lunar lander to reach the surface of the Moon and commence operations.

The vehicle is intended to have an operational lifespan of 14 days (one lunar day), and carries 10 experiments which utilise the lander’s solar power generation system. Roughly the size of a small car, the vehicle landed not in the southern polar regions of the Moon – the target area for Artemis missions – but within Mare Crisium, a 556 km basin to the north-east of Mare Tranquillitatis, the region in which Apollo 11 landed in 1969.

Despite this more northerly landing location, the mission’s objectives remain in line with Artemis, being intended to gather additional data on the properties of lunar regolith, together with its geophysical characteristics, as well as measuring the interactions between Earth magnetic field and the solar wind – all of which will help in the preparations for the long-term human exploration of the Moon and “routine” travel between Earth and cislunar space.

And if you’re wondering about Blue Ghost’s companion during the launch for Earth, Japan’s Resilience, which also carries a lunar rover, is taking the “scenic” route to the Moon, arriving there in early June 2025, at which point I’ll hopefully have an update on that mission.

However, Blue Ghost was not intended to be the only US lander reaching the Moon in early 2025. Also a part of NASA’s CLPS programme, the Athena lander, built and operated by Intuitive Machines, had been slated to arrive on the Moon and commence operations on March 6th, having also been launched on its way to the Moon atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 on February 27th, 2025.

Officially designated IM-2 / CLPS-3, the lander – christened Athena and classified by the company as a Nova-C lander – was the second lunar lander mission undertaken within the CLPS programme by Intuitive Machines, their first having been launched to, and reaching, the Moon in February 2024. However, that lander, called Odysseus, toppled over on landing (see: Space Sunday: Lunar topples, space drugs and wooden satellites), effectively ending that mission.

Like Odysseus, the IM-2 mission was targeting the Lunar South Polar Region for a landing, in this case the tallest mountain on the Moon to be given its own name (in 2022): Mons Mouton, named for Melba Roy Mouton, a pioneering African-American mathematician at NASA during the 1960s, the peak having previously been regarded as part of the broader Leibnitz plateau. In addition to its own science mission, the lander also carried a trio on small-scale landers – Grace, a hopper-style mini-rover also made by Intuitive Machines and massing just 1 kg; the Mobile Autonomous Prospecting Platform (MAPP), a 5-10 kg rover with a 15 kg payload built and operated by a consortium; and AstroAnt, a matchbox-size micro rover from MIT, which would have trundled around the back of MAPP using magnetic wheels taking measurements on the amount of heat absorption and heat radiation to help determine the thermal regulation requirements on future rovers operating within the temperature regimes of the lunar South Polar Region.

Both Athena and Odysseus share the same overall design, being very tall, slim vehicles with elevated centres of mass. With Odysseus, this appeared to combine with a horizontal drift of the vehicle during its landing attempt (the vehicle’s telemetry indicated it was crabbing sideways at around 3.2 km/h at touch-down, rather than descending vertically), to cause it to topple over.

On March 6th, 2025, Athena appeared to suffer a similar fate: as the vehicle neared the surface of Mons Mouton, its motors kicked-up a plume of dust which prevented the vehicle’s lasers and rangefinders from guiding the spacecraft. While data was received to indicate Athena had landed, it also indicated the loss of one of the lander’s two communications antennas and that power was being generated by the vehicle’s solar arrays well below nominal levels.

Subsequent to the landing, the mission team placed Athena into a “safe” mode to conserve power. However, images taken by both the lander and from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) as it passed over the landing site confirmed Athena had toppled over on touch-down and to be laying in a small, shallow crater, either as a result of sideways drift in the final phase of landing or as a result of one of more landing legs overhanging the edge of the crater at touch-down.

Despite the fall, Intuitive Machines regard the mission as a “success” inasmuch as the vehicle returned data all the way up to the point of landing, and was able to briefly power-up some of the on-board instruments despite falling into the crater. However, given this is the second incident wherein a tall, slim lander with a high centre of mass has toppled over when landing in what is acknowledged to be one of the toughest and mostly unknown regions of the Moon to reach, it could call into question the suitability of the SpaceX 50-metre tall human landing system (HLS) to successfully make similar landings within the environment.

X-37B Returns Home

The US Space Force’s highly-secretive X-37B space plane returned to Earth on Friday, March 7th (UTC), marking the end of a 434-day mission in orbit. The 9-metre long automated vehicle – one of two currently operated by the USSF – originally lifted-off from Kennedy Space Centre’s Lunch Complex 39A (LC-39A) atop a SpaceX Falcon Heavy booster in December 2023, on the seventh overall flight of the Orbital Test Vehicle mission (OTV-7).

As with the previous six missions in the programme, much of OTV-7 was completed in a blanket of secrecy; however, unlike them, the mission did not continue to push the envelope of flight duration. Whereas the 2nd through 6th OTV flights repeatedly increased the number of days one of the vehicles could spend in orbit (from 224 days in the case of the first mission to just under 3 hours shy of 909 days in the case of OTV-6), this seventh flight was the second shortest to date.

Which is not so say it was without precedent; whilst the previous missions had been confined to the sphere of low-Earth orbit operations, OTV-7 saw the spacecraft placed into a highly elliptical orbit (HEO0, with a perigee of just 323 km, and an apogee of 38,838 km. This orbit not only illustrated the vehicle’s ability to operate at significant distances from Earth, but also allowed it to demonstrate its ability to using aerobraking – dipping into the upper reaches of Earth’s denser atmosphere as a means to both decelerate a space vehicle and / or to alter its orbit. Whilst often used by robotic missions to Mars and Venus, the aerobraking by OTV-7 marked a first for a US winged space vehicle, giving the X-37B an additional operational capability, such as detection avoidance by altering both orbital inclination and altitude during such a manoeuvre, a capability which could be extended to future generations of US military satellites.

In another departure from previous missions, in February 2025, the US Department of Defense (DoD) released images taken from the X-37B while in space – the first time any such pictures of the vehicle on-orbit have entered the public domain.

Following a de-orbit burn of its main propulsion system, the X-37B vehicle successfully re-entered the Earth’s atmosphere and glided to a landing on Vandenberg Runway 12, wheels touching down at 07:22 UTVC on Friday, March 7th, 2025. There is obviously no word on when one of the vehicles might next be placed into orbit.

Starship Blows It – Again

On March 6th, 2025, and less than two months after their previous attempt, SpaceX tried to deliver one of their Starship vehicles onto a sub-orbital flight. Called Integrated Flight Test 8 (IFT-8), the flight was intended to be something of a repeat of January’s IFT-7 – and it turned to be almost a direct carbon copy of that flight in more ways than intended.

The primary goals of the mission were to:

- Launch the combined vehicle and recover the booster at the launch site.

- Deliver a Starship “block 2” vehicle incorporating numerous design changes into a sub-orbital track and deploy a series of dummy Starlink satellites & carry out an on-orbit re-light of some of the vehicle’s engines to simulate a de-orbit burn.

- Starship re-entry and possible splashdown, testing new thermal projection system tiles and the function of the redesigned forward aerodynamic flaps.

What was not on the cards was an almost to-the-minute loss of the Starship vehicle in what appears to have been very similar circumstances to the last flight – and with an initially similar aftermath.

The first goal of the mission was carried out successfully: the 123-metre tall stack of Super Heavy vehicle and Starship vehicle departed the launch facility at Boca Chica, Texas, at 23:30 UTC, with the booster pushing the Starship up to the assigned “hot staging” altitude. At this point, the vehicles separated, and the booster completed the necessary “boost back” operations to return to the launch site and be “caught” by the “chopstick” arms on the launch tower 7 minutes and one second after its initial departure.

However, and echoing the events of January’s IFT-7, the Starship vehicle encountered what appear to again be engine / engine bay related issues. At 7 minutes 45 seconds into the flight, images from inside the vehicle’s engine skirt showed both clouds of propellant gases streaming around the exhaust bells of the inner three sea-level Raptor engines, together with signs of some form of burn-through on the engine bell of one of the outer large vacuum Raptor engines (referred to as “Rvacs”). The images were followed at 8:04 into the flight by the premature shut-down of an Rvac motor, followed in rapid succession by all three sea-level engines.

With just two fixed Rvac motors running, the vehicle entered an uncontrolled tumble and likely started to break-up somewhere between 9:19 and 9:30 into the flight. Shortly after this, observers in parts of the Caribbean, from the Dominican Republic to the Bahamas, and as far north as Florida’s Space Coast, reported seeing the vehicle explode and debris falling. As a result, and as with IFT-7, the FAA implemented a number of debris response areas along the vehicle’s flight path over the Greater Antilles, closing off airspace. This resulted in some flights either being placed in holding patterns outside the threat areas, or being diverted to other airports or being held on the ground.

Following the loss of the vehicle, the FAA once again suspended the Starship launch license and announced a mishap investigation to be led by SpaceX. This is common practice – the operator leading the investigation into the loss of their vehicle, with FAA having oversight and a final say in allowing the resumption of flights. However, what is far from usual is that the launch operator takes it upon itself to unilaterally declare the issues surrounding the vehicle loss had been investigated and resolved, and launches would therefore be resuming. However, this is precisely what happened in the case of IFT-7 on February 24th, 2025, with the FAA (now very much under the thumb of the SpaceX CEO in his “special appointment” role within the Trump administration) releasing the license to allow Starship operations to resume whilst leaving their investigation open.

As such, there are significant question to be asked in relation to both what actually happened following IFT-7 in terms of issue rectification, whether the loss of IFT-8 might indicate a significant design flaw in the Starship “block 2” vehicle, and whether or not the FAA’s ability to properly manage oversight of commercial space companies – or at least SpaceX – may have been compromised given the SpaceX CEO’s new position of authority within the Trump administration (although getting an answer to this question is highly unlikely).