Update, Monday August 6th: Curiosity arrived on Mars, on time and on target, the start of what promises to be a remarkable mission of exploration. Mars was good, and allowed the rover to pass images over to Mars Odyssey for transmission to Earth. Read my report.

Later today – or in the early hours of the morning of Monday 6th August if you live on the East Coast of the USA or in Europe, something very, very remarkable will take place above the magnificent vistas of Mars: NASA’s latest mission to the Red Planet will arrive in a quite spectacular manner.

The Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission is the biggest single payload yet sent to Mars. It comprises a rover vehicle called Curiosity, weighing-in at almost a tonne, carrying a sophisticated science laboratory that gives the mission its name. The latter is designed to study the Martian climate and to analyse soil and rock samples to assess what the Martian environment was like in the past in terms of its potential to have been the abode of life. To contribute to thee goals, MSL has six primary mission objectives:

- Determine the mineralogical composition of the Martian surface and near-surface geological materials.

- Attempt to detect chemical building blocks of life (biosignatures).

- Interpret the processes that have formed and modified rocks and soils.

- Assess long-timescale (i.e., 4-billion-year) Martian atmospheric evolution processes.

- Determine present state, distribution, and cycling of water and carbon dioxide.

- Characterize the broad spectrum of surface radiation, including galactic radiation, cosmic radiation, solar proton events and secondary neutrons.

In addition, and while en-route to Mars, the mission has been measuring the radiation exposure experienced by the interior of the vehicle while in interplanetary space in order to better understand that medium in preparation for manned deep-space missions into the solar system.

The Rover

While some to the media descriptions have been prone to exaggeration where Curiosity is concerned (comments like “the size of an SUV” leading people to visualise something the size of a Range Rover or Jeep Cherokee), one should not doubt that, comparatively speaking, the rover is big. At around 3 metres (approx 10ft) in length, Curiosity is almost twice the length of the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER) Opportunity and Spirit already on Mars, while at 900kg (1984 pounds), it is almost two-and-a-half times heavier than their combined weight.

The MERs, which arrived on Mars in 2003, were both solar-powered, as was NASA’s first mission to put a rover on Mars – the tiny Sojourner, which formed a part of the Mars Pathfinder mission of 1997. As such, the MERs were expected to only operate for some 90 days apiece – even though Opportunity is still functioning today (over 3,100 days into the mission). One of the reasons for the 90-day limit placed on the MER missions was the expectation that the rovers solar arrays would become less and less effective as the mission progressed due to the accumulation of Martian dust on their flat surfaces, reducing the amount of sunlight they could convert into power for the rovers’ battery systems. This actually did occur, but so did a series of (initially unexpected) “cleaning events”, which saw the Martian wind periodically remove dust from the arrays, restoring some of their ability to harness sunlight.

MSL is expected to operate for far longer than the MERs – a full Martian year (just under 687 days) being the planned initial mission period. It also carries far more science and other equipment on-board. As such, solar power for the vehicle is impractical. Instead, it will be powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), which utilises heat from the radioactive decay of plutonium-238. This produces around 110 watts of electrical power, generating around 2.5 kilowatt hours per day (compared to the 0.6 kilowatt hours per day generated by the MERs). In addition, the heat generated by the radioactive decay is used to warm fluids which are circulated through the rover keep electronics and other systems at acceptable operating temperatures during the harsher periods of the Martian / seasons.

MSL is not the first time RTGs have been flown to Mars by the United States; both of the Viking Landers of the 1970s were RTG-powered, and both of them, like Spirit and Opportunity, functioned well beyond their original mission times, with Viking Lander 1 operating for over six years and Viking Lander 2 for just over three-and-a-half years.

Once on the surface, Curiosity will be able to traverse the terrain at a maximum speed of some 90 metres (300ft) per hour, with average traverse speeds of around 30m (100ft) per hour. This compares to the MERs traversing around 100 metres per day, and means that over the course of the initial mission period, the rover should cover a minimum of some 19 kilometres (12 miles) during the initial mission period (Opportunity has, to date, travelled some 34.6 kilometres (21.5 miles). The rover will be able to calculate the distance it has travelled by means of the unique pattern the wheel treads will leave in the Martian sand; included in the thread pattern is the Morse code pattern for JPL (·— ·–· ·-··), which will be imprinted on the Martian soil once every revolution (JPL standing for “Jet Propulsion Laboratory, MSL’s “home”). In addition, Curiosity will be able to roll over obstacles approaching 75 cm (30 in) in height.

Science Instruments

Some 80 Kg of Curiosty’s mass comprises the camera systems, scientific instruments, experiments and operating systems themselves. These include two on-board computer systems responsible for managing all of the rover’s operations. Both of these are radiation-hardened, with one forming the back-up to the other in case of unexpected failure. Each computer has just over 2Gb of memory and a RAD750 CPU. For navigation, the computers are supported by an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) that provides 3-axis information on its position.

MSL includes a suite of camera systems, which will be used for a range of functions, including autonomous navigation, hazard avoidance cameras (using pairs of black-and-white cameras mounted at each corner of the rover), a “Mars Hand” camera mounted on the rover’s robotic arm (which has a reach of some 2 metres) capable of taking microscopic images of rock and soil, a “ChemCam” which uses an infra-red laser to vaporise rock and soil samples and then collecting a spectrum of the light emitted.

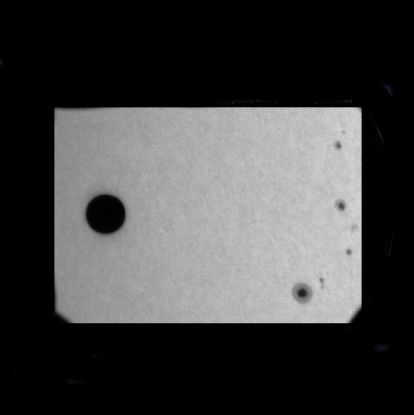

From a public perspective, however, the two most interesting camera systems aboard the rover are liable to be the Mars Descent Imager (MARDI) and the MastCam. MARDI will be used during the final moments of MSL’s Martian arrival (dubbed, with good reason, the “seven minutes of terror” – see below). This is designed to start operating when the MSL and its decent unit are some 3.7 km above the surface of Mars and continue through until the vehicle is some 5 metres above the surface. It will take images at 1600×1200 pixel resolution with a 1.3 millisecond exposure time and at a rate of some 5 frame per second.

The MastCam sits (as the name suggests) atop the rover’s mast, some 1.97m above the bottom of the rover’s wheels. This system provides multiple spectra and true color imaging with two cameras. The cameras can take true color images at 1600×1200 pixels and up to 10 frames per second hardware-compressed, high-definition video at 720p (1280×720). As such, it is liable to be images and film from this camera that will capture the imagination of people from around the globe, with the two cameras in the system given between 1.25 and 3.67 higher spatial resolution than the panoramic cameras carried by the MERs when operating at its highest (black and white) resolution of 1024×1024 pixels.

NASA JPL provides a comprehensive overview of the complete science package for those who are interested.

Use the page numbers below left to continue reading