As we’re at the end of 2024, rather than looking back over the year, I thought I’d look ahead to some of the spaceflight events hopefully coming our way in 2025. Note this list intentionally does not include schedule missions to the ISS, SpaceX Starlink launches or test programmes, or similar.

New Glenn Maiden Flight

While Blue Origin didn’t meet their target to fly their new heavy lift launcher, New Glenn, before the end of 2024, the flight now looks set to go ahead in early January 2025. Specifically:

- On December 27th, 2024, and after some delay, the company finally received a license from the FAA to conduct New Glenn launches out of Canaveral Space Force Station for five years.

- That same day, the rocket, which has been on the pad for final testing, completely a full static fire test of its core stages engines. The test saw all seven core stage engines run for a total of 24 seconds, over half of which saw them throttle up to 100%.

- While a launch date has not been disclosed by Blue Origin, an airspace advisory has been released referencing NG-1, the name of the flight, and warning of airspace restrictions around and over Florida’s Space Coast for the period 06:00 through 09:45 UTC on January 6th, 2025, with the option for a second airspace restriction being enforced at the same time on January 7th, 2025.

As I’ve previously noted, the flight will be carrying a prototype Blue Ring satellite platform capable of delivering up to 3 tonnes of payload to different orbits, as well as being able to carry out on-orbit satellite refuelling (as well as being refuelled in orbit itself) and transporting payloads between orbits. However, Blue Ring will not physically detach from the launch vehicle’s upper stage for the flight. Additionally, the flight is seen as the first of two flights required to certify New Glenn to fly United States Space Force national security and related payloads, and will hopefully see the first stage make a safe return to Earth and landing on the company’s Landing Platform Vessel 1, Jacklyn.

Japan Goes Lunar Roving

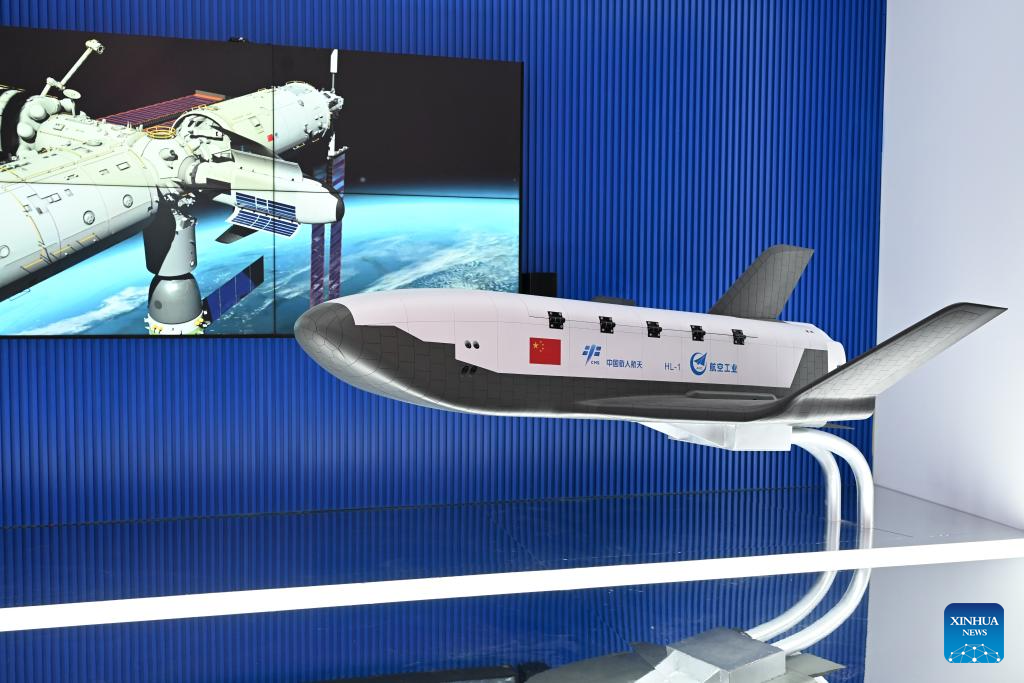

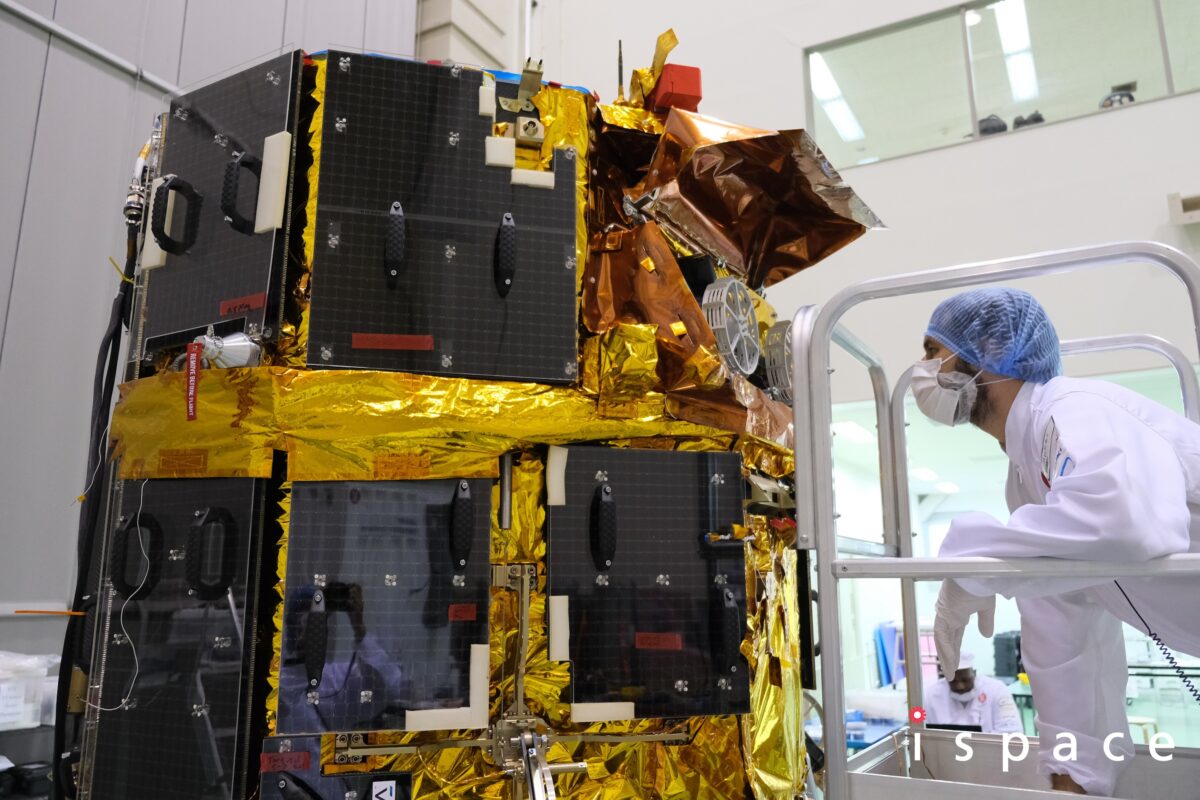

January is also the target month for Japan’s second attempt at a private lunar landing, in the form of the Hakuto-R Mission 2, developed by ispace. It is a follow-up to the Hakuto-R Mission 1, a technology demonstrator mission also launched by ispace, which took the “long way” to the Moon, covering a total of 1.4 million kilometres in a 5-month journey.

However, the lander and its payloads were lost during it landing attempt on April 23rd, 2023, after a disagreement between the main flight computer and the vehicle’s altimeter resulted in it entering a sustained hover some 5 km above the lunar surface, expending its propellants so it fell uncontrolled to the Moon’s surface.

Like its predecessor, Hakuto-R Mission 2 comprises a lander vehicle some 2.5 metres tall and 2.3 metres wide intended to demonstrate a reliable small-scale lander capability with data transmission and relay capabilities for use as a part of the US-led Project Artemis. The lander will launch atop a SpaceX Falcon 9, but unlike it predecessor will head directly to the Moon, where it will land in Mare Frigoris, the Sea of Cold.

Once there, the lander – called Resilience – will deploy a micro-rover called Tenacious. Weighing just 5 kg, this has been built as a multi-role vehicle by a team in Luxembourg. Once deployed, it will demonstrate autonomous driving capabilities as it explores the area around the lander, and will also partner with the lander in an ISRU (in-situ resource utilisation) demonstration, attempting to extract water from the lunar surface, heating it and splitting the resultant steam into oxygen and hydrogen.

The mission will carry a number of additional payloads, perhaps the most unusual of which is Moonhouse, by Swedish artist Mikeal Genberg.

For 25 years, Genberg has had a dream about a little red house (“all house in Sweden are red!” he states) on the Moon; throughout that time he’s visualised it through art installations here on Earth, and has even seen one of his models flown aboard the space shuttle, courtesy of Swedish astronaut Christer Fuglesang. Now, Tenacious will carry one of Genberg’s little houses to the surface of the Moon. It is secured to a platform on the front of the rover, and represents the culmination of Genberg’s 25-year-long dream.

As to its meaning – Genberg notes that it could be many things, depending on who you are. A symbol of life; for the potential for future life; a beacon of hope that anything is possible if we put our minds to it; a commentary on humanity and our treatment of the one home we have; as art, it has the ability to speak to each of us, and to do so differently with each of us.

Fram2 Private Polar Mission

Due to launch in around March 2025, Fram2 is another “all-private” space mission in the mould of Jared Isaacman’s Inspiration4 (2021) and Polaris Dawn (2024) flights. Also utilising SpaceX Crew Dragon Resilience, Fram2 will fly a crew of 4 on a mission of up to 5 days duration in a 90º inclination orbit between 425 and 450 km altitude. It aims to observe and study aurora-like phenomena such as STEVE and green fragments and conduct experiments on the human body, including the first X-ray of a human in space.

The crew for the mission comprise:

- Chung Wang, the mission commander and co-bankroller, a Chinese-born Maltese crypto currency entrepreneur who founded f2pool , one of the largest Bitcoin mining pools in the world, and Stakefish, one of the largest Ethereum staking providers.

- Jannicke Mikkelsen, the vehicle commander, and co-bankroller for the mission, a Scottish-born Norwegian cinematographer and a pioneer of VR cinematography, 3D animation and augmented reality. A skilled speed skater, she will become the first Norwegian astronaut and the first European to command a space vehicle.

- Eric Philips, a 62-year-old noted Australian polar explorer, who will serve as the vehicle pilot as will be the first Australian national to fly in space (while both Paul Scully-Power and Andy Thomas were born in Australia and flew on space shuttle missions (Thomas flying multiple times), they only did so after becoming US citizens).

- Rabea Rogge, a German electrical engineer and robotic expert, who will fill the role of Mission Specialist and will become the first German woman to fly in space, beating-out those selected as a part of the privately-funded programme Die Astronautin, specifically set-up to fly a German woman in space by 2023.

Fram2 is named for the Norwegian polar exploration vessel Fram, a veteran of multiple expeditions to both poles between 1883 and 1912, including Roald Amundsen’s historic 1910-1912 southern polar expedition, is planned to launch in March 2025.

Tianwen-2: Asteroid Sample Return Mission

China will continue its deep-space exploration ambitions with the planned May 2025 launch of Tianwen-2 (“’Heavenly Questions-2”) robotic vehicle. Whilst bearing the same name as the highly-successfully mission to place an orbiter around Mars and a lander and rover on the surface of that planet in 2021 (and covered within past Space Sunday articles), Tianwen-2 is a very different mission: that of rendezvousing with, and landing on, a near-Earth object (NEO) asteroid and gathering up to 100 grams of material for a return to Earth.

The target for the mission is a quasi-moon 469219 Kamoʻoalewa, thought to be around 40-100 metres along its longest axis. It orbits the Sun at distance of between 0.9 and 1.0 (the average distance of the Earth from the Sun) and with an orbital period of 365-366 days. This makes it appear as if it moving around the Earth, although it is in fact oscillating around the L1 and L2 and L4 and L5 positions, and not actually gravitationally bound to Earth, never coming closer than some 14 million kilometres.

What is particularly interesting about 469219 Kamoʻoalewa, first identified in 2016, is that spectral analysis suggests it is likely silicate in origin; combined with its orbit, this points to it possibly being a lump of rock ejected from our Moon as a result of an asteroid impact. However, it could equally be an S-type asteroid (which account for around 17% of all known asteroids) or possibly an L-type, which are exceptionally uncommon.

Thus, given the mix of potential heritage, 469219 Kamoʻoalewa has been seen as an intriguing subject for up-close study ever since its identification, and a number of proposals have been put forward up-close study, as well as being the target for observation by numerous Earth-based telescopes. Following launch, Tianwen-2 is expected to intercept the asteroid in 2026, and conduct remote sensing activities which will include identifying locations for sample acquisition. It will also deploy both a nano-orbiter and a nano-lander for independent study of the asteroid.

To collect samples, Tianwen-2 will send down a sample gathering unit which will conduct both touch-and-go operations similar to those used by Japan’s Hayabusa2 probe sent to obtain samples from the near-Earth asteroid 162173 Ryugu (2014-2020), and NASA’s OSIRIS-REx (2016-2023) mission to gather samples from asteroid Bennu, and also anchor-and-attach – the first time such a technique will be attempted.

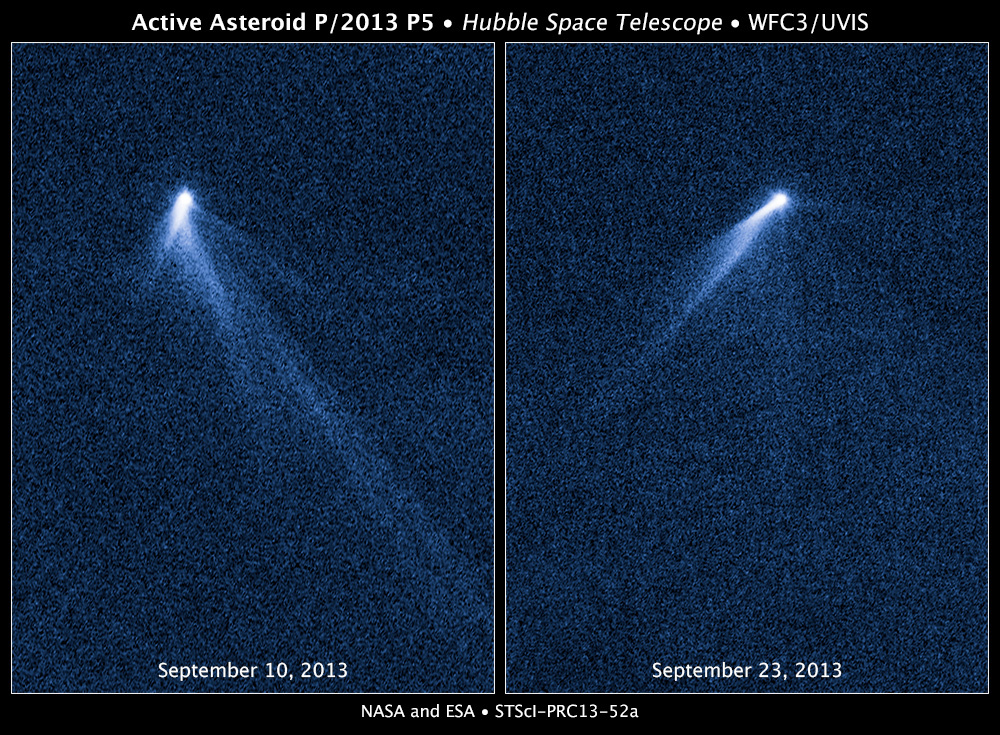

After gathering samples, Tianwen-2 will depart 469219 Kamoʻoalewa and make a fly-by of Earth in 2027, which it will use to both drop-off its sample capsule and also complete a gravity assist manoeuvre in order to travel on to rendezvous with active asteroid 311P/PanSTARRS, which orbits the Sun every 3.24 years and exhibits the characteristics of both an asteroid and a comet, including having up to six comet-like tails.

Estimated to be around 240 metres across and always orbiting the Sun beyond the orbit of Mars, 311P/PanSTARRs was first identified in 2013, and observations in 2018 suggested it might have a companion orbiting it. Tianwen-2 is expected to reach it in 2034.

Dream Chaser Rises

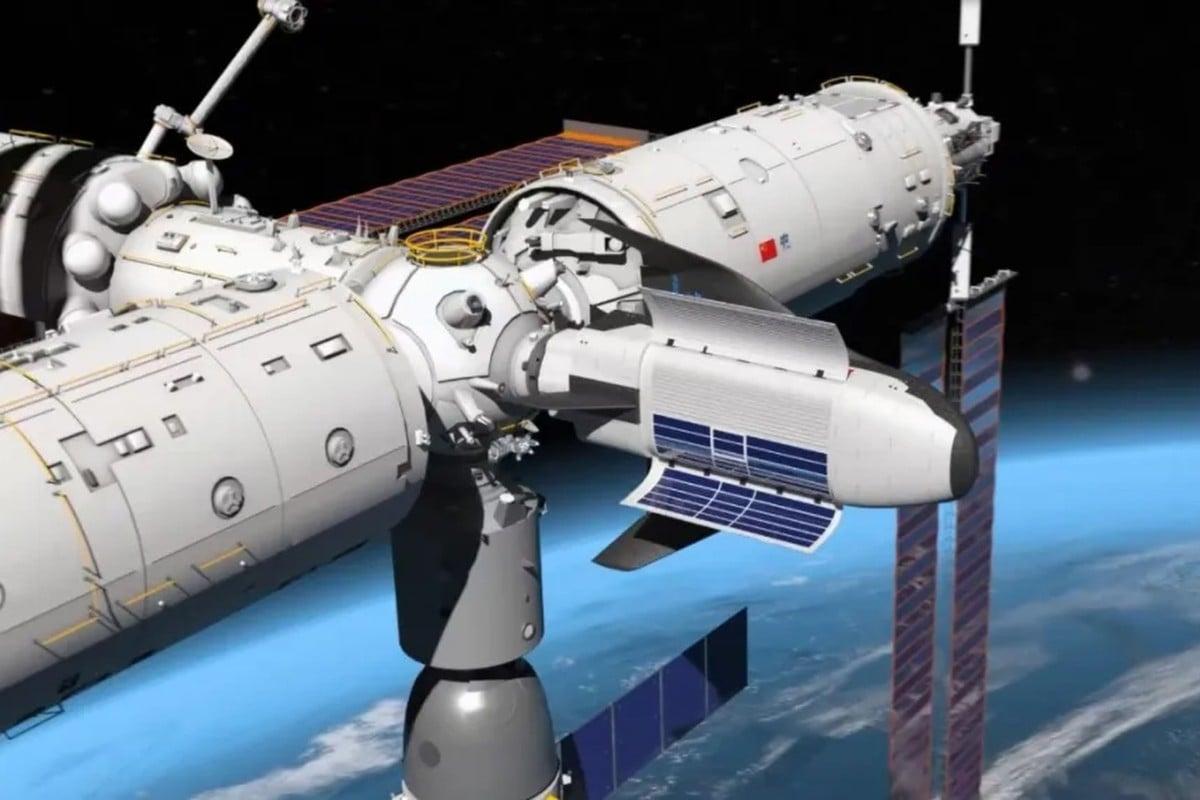

May is the month that will hopefully see the launch of the newest addition to the fleet of vehicles that help keep the International Space Station (ISS) well-stocked with supplies and operational, when a ULA Vulcan Centaur VC4L lifts-off from Space Launch complex 41 at Canaveral Space Force Station, carrying Tenacity, the first Dream Chaser Cargo vehicle from Sierra Space.

Referred to SSC Demo-1, the mission will see Tenacity and its Shooting Star power and cargo module carry out a check-out mission of up to 45 days duration which will see the combined vehicle rendezvous and dock with the ISS, undergoing check-out by ISS crew and eventually undocking, after which the Shooting Star module will be jettisoned and Tenacity will return to Earth for an aircraft-style landing at the former Space Shuttle Landing Facility, Kennedy Space Centre.

When operational, Dream Chaser with Shooting Star will have the largest all-up payload capacity of any ISS resupply vehicle: 5.5 tonnes; 5 tonnes of which can be pressurised. However, missions will likely be flown with lesser payload amounts. In addition, Dream Chaser can return to Earth with payloads of up to 1.75 tonnes, comprising equipment, experiments and general waste.

Six Dream Chaser resupply missions to the ISS have been contracted, using at least two Dream Chaser vehicles, Tenacity and Reverence (although construction on the latter is currently suspended). The date of the first operational flight (CRS SSC-1) has yet to be given, but is unlikely to be before 2026.

Space RIDER Flies

The European Space Agency (ESA) is expected to debut its entry into the reusable spaceplane market in the latter half of 2025 with the maiden flight of Space RIDER (Space Reusable Integrated Demonstrator for Europe Return), a two-stage vehicle designed to provide routine and relatively low-cost capabilities to delivery payloads of up to 620 kg to low-Earth orbit.

I’ve covered Space RIDER in the past, but briefly, it is a small-scale reusable lifting body supported by an expendable service module which supplies it with main propulsion and electrical power when in orbit, prior to being jettisoned before the main vehicle re-enters the atmosphere. Payloads are intended to be experiments and science instruments, which the vehicle returns to Earth at the end of a mission, although it will have the ability to deploy smallsats in space as well.

Massing 4.9 tonnes at launch (including the service module), the lifting body – referred to as the Re-entry module (RM) – masses 2.8 tonnes on landing. The combined craft has a length of just over 8 metres, of which 4.6 metres is that of RM, which includes a payload volume of 1.2 m³.

Designed to be launched atop ESA’s Vega-C rocket, Space RIDER can remain in orbit for up to 2 months at a time conducting experiments. Following re-entry, the RM will use its lifting body shape to drop its speed from Mach 25 to Mach 0.8 (roughly the speed of an commercial airliner) as it descends, prior to deploying a drogue parachute at between 12-15 km altitude, which will slow it to around Mach 0.22. After this, a parafoil is deployed, which allows the vehicle to glide under control to a horizontal landing. It is designed to make up to six flights into space, and has a turnaround time of “less then 6 months”.

The Year of Fly-bys

2025 is going to be a year of fly-bys for several deep space missions, including:

- January: The ESA / JAXA BepiColumbo mission to Mercury will complete its sixth and final fly-by of the planet as it uses Mercury’s relatively weak gravity to both decelerate and swing it on to a trajectory from which it can establish itself in orbit around the planet. The manoeuvre will mark the end of 9 fly-bys of three planets – Earth (1); Venus (2) and Mercury (6); the next time the probe reaches Mercury (after another passage around the Sun) in November 2026, it will fire its motor and enter orbit ready to commence its primary science mission, over 8 years after its launch.

- March: ESA’s Hera mission, launched in October 2024, will perform a fly-by of Mars en route to its final destination, the Didymos binary asteroid system, where it will carry out a detailed study of the aftermath of the NASA Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) which impacted the asteroid Dimorphos in an attempt to deflect it in its orbit around the larger Didymos.

- March: NASA’s Europa Clipper mission will also fly-by Mars as it makes its way towards Jupiter in order to study the icy world of Europa. The second of two such mission to be launched – the other being ESA’s Juice mission (see below), The NASA mission will make better progress to Jupiter by virtue of being launched atop a more powerful rocket – the SpaceX Falcon Heavy.

- April: NASA’s Lucy mission will complete its fourth fly-by of a celestial body, and the second of a main belt asteroid – 52246 Donaldjohanson, named for the paleoanthropologist who discovered the famous “Lucy” fossil. This vehicle is on a complex mission to examine eight separate asteroids (2 within the main belt between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter; four more in the L4 Trojan cloud occupying the same orbit a Jupiter, but 60º, which it will reach in 2027; and a pair within the Trojan cloud trailing Jupiter in its orbit by 60º, which it will reach in 2034 after a further fly-by of Earth at the end of 2030.

- August: ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) will make a fly-by of Venus as it gathers the momentum it needs to reach Jupiter and start its studies of Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. The fly-by of Venus will be the second of four such manoeuvres, the other three (August 2024, September 2026, January 2029) being around Earth.