On October 21st, 2000, a Soyuz vehicle lifted-off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan en route for the fledgling International Space Station ISS, carrying two cosmonauts and an American astronaut. Sergei Krikalev, Yuri Gidzenko and William Shepherd were not the first people to visit the ISS, but when Soyuz TM-31docked with the station on November 2nd, they became the first official crew to live and work aboard it, and their arrival marked the start of 20 years of continuous occupation of the station.

At the time of the arrival of the Expedition 1 crew, the ISS was a small affair, the Russian-built Zarya propulsion, attitude control, communications and electrical power distribution module, launched in 1998; the American Unity module, intended to link future US and international modules on the station with the Russian units, delivered by the shuttle Endeavour in 1998; and the Russian Zvezda, which rendezvoused and docked with the station in July 2000.

The primary role of the Expedition 1 crew was to commission the ISS and its systems and to oversee the initial expansion of the station, with the assistance of two space shuttle flights. The first of these delivered the additional solar arrays to power the station, elements of the “keel” of the station (the Integrated Truss Structure), and the second the US Destiny research module. However, the work wasn’t all construction related: the three men also started the station’s long-running science programme that continues through to today. They also caused a slight controversy as they started work.

The idea of a US space station has started to come together in the 1980s under the project title Space Station Freedom. This was later revised to Space Station Alpha before finally becoming the International Space Station following the signing of a US / Russian agreement to build a joint orbital facility. However, the “Alpha” name stuck with many at NASA, including Expedition 1 commander Shepherd, who insisted on using it – much to the consternation of Russian officials, who felt they had had the first space station in Salyut and Mir, so the new station was at best “Beta” (or better yet in their eyes, Mir -2).

Once aboard the station, and with the agreement of Krikalev and Gidzenko, Shepherd insisted on using “Alpha” as the station’s radio call sign, stating it was easier to say than “International Space Station” or “ISS”. Despite the annoyance on the part of Russia, “Alpha” continued to be used by the Expedition 1 crew, resulting in it being adopted as the station’s official radio call-sign.

As well as playing hosts to three space shuttle missions – the third of which delivered the Expedition-2 crew -, Shepherd Krikalev and Gidzenko also oversaw the start of re-supply missions using the Russian Progress vehicles (essentially fully automated Soyuz vehicles) capable of delivering around 2.4 tonnes of supplies and fuel to the ISS.

Following Expedition-1, the initial crews visiting the ISS were exclusively made up of Russian cosmonauts and American astronauts, with each crew spending, on average, 5-6 months on the station. It was not until June 2006 that the first international crew member boarded the ISS in the form of German astronaut Thomas Reiter. He was followed in 2008 by Frenchman Léopold Eyharts and Japan’s Koichi Wakata in 2009 (Wakata actually served a total of 5 Expedition crew rotations: 18, 19, 20 (all back-to-back and continuous) and 38 and 39 (again back-to-back). After this, crews routinely included one or more non-American / Russian astronaut.

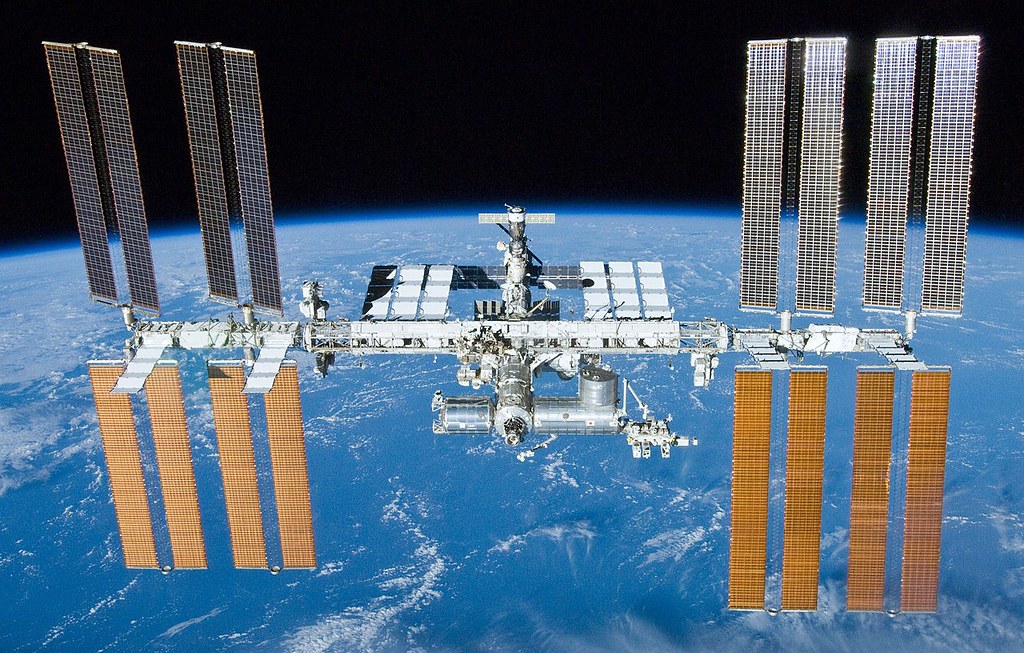

In the 20 years since Expedition-1, 240 individuals have made 395 flights to the ISS (including 7 “space tourists”) – a number that represents 43%of all human flights into space. In that time, the space station has grown from those initial three units to a total of 16 permanent pressurised modules, numerous unpressurised pallets and work stations, and one commercial unit, the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM), an inflatable unit, currently configured as a storage space.

Outside of the Zarya, Zvezda, Unity and Destiny modules, the ISS comprises the following pressurised modules:

- For science: the Columbus European module (added February 2008); the Japanese Kibō module (which, with its unpressurised work platform is the largest crewed elements of the ISS, added between 2008 and 2009); the Russian Rassvet module (now primarily used for storage, added May 2010).

- Airlock / docking: the US Quest Joint Airlock, supporting EVAs using either US or Russian space suits (added July 2001); the Russian Pirs and Poisk airlock / docking modules (added September 2001 and November 2009, respectively, and connected to the Zvezda module); the US International Docking Adapters 2 and 3 (IDA-1 was lost in a Falcon 9 launch failure), delivered in 2016 and 2019 respectively.

- Other modules: the US Harmony “hub node” connecting the European and Japanese science modules to the US Destiny module (added 2007); the European Tranquillity life-support and environmental module (added November 2009); the Leonardo European multi-purpose module (added February 2011) and the European Copula module, with its seven large windows (added in 2010).

Together, the pressurised modules of the ISS offer a volume of living / working space equitable to that of a 747 airliner. The overall mass of the ISS, including the Truss, and all unpressurised / external elements is approximately 425 tonnes.

Nor is this all: four more Russian modules are awaiting launch to the ISS: the Nauka Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM). Delayed since 2007, it is currently slated for a 2021 launch, but this may yet be cancelled as the warranties on several of the module’s system expire in later 2021; the Prichal “docking bell”, primarily intended to provide docking for two further power modules (SPM-1 and SPM-2) and for Soyuz / Progress docking. Prichal is slated for launch in late 2021, and the two SPM units in 2024.

Further commercial elements are also due to be added in the form of the Bishop Airlock Module, designed for the launch of cubesats from the station (and awaiting launch before the end of 2020), and the Axiom commercial node, due to be added in 2024.

The living spaces on the ISS can support up to 6 crew at a time, although the standard crew complement outside of rotation periods, when two crews are operating side-by-side, has tended to be 3 (even when the shuttle was still operational). With the arrival of the SpaceX Crew Dragon and the Boeing Starliner, crews can now increase to 4-6, depending on requirements.

However, we’re not talking glitzy, hi-tech living. Despite its volume, the ISS is cramped; personal space is limited to a couple of cubic metres (mostly used to hang an astronaut’s sleeping bag), and “free” space has become increasingly overcrowded with the passing years as more and more equipment has been packed into the various modules.

The lack of gravity means that almost any surface can be used as a floor, ceiling or wall, depending on a person’s orientation. However, to try to keep a general sense of orientation within the Russian modules, surfaces facing towards Earth are considered “down” and are coloured olive green; surfaces pointing away from Earth are considered “up”, and are painted beige. Perpendicular surfaces between them flow from the one colour to the other as you look “up” or “down”.

Doe to the lack of personal space, almost any “free” space on the structural walls / ceilings / floors of the various modules tend to become the home of personal and other mementos. One area of the Zvezda module, for example, has been turned into a corner for expressions of the Russian orthodox faith, and another a shrine to Russian heroes of space flight and discovery from Tsiolkovsky to Gagarin.

The two most popular areas of the station are the Harmony module, with its communal dining area, which is also used to celebrate birthdays, anniversaries, holidays, etc., and the European Copula, due to its unparalleled views out of its windows. Overall, however, life on the ISS is described as, “noisy, smelly [if your sinuses clear, as they are usually blocked due to the lack of gravity], dirty and awash with everything from human skin and floating globs of sweat [crew are expected to undertake around 2 hours of physical exercise a day] to the pencil you misplaced yesterday and which is now floating around in the air currents between modules,” with the noise being noted as the biggest issue.

The scientific range of the ISS has been, and remains, extensive. Human and life sciences space research includes the effects of long-term space exposure on the human body, testing medical systems and procedures specifically aimed towards supporting long-duration space missions (e.g. to Mars and back), zero-ego production of pharmaceuticals to help with ailments on Earth (the lack of gravity allows compounds to be mixed that would otherwise naturally separate). The broader aspects of life sciences have included the growth of unique protein crystals, and the evolution, development, growth and internal processes of plants and animals.

A second major area of research has been materials science. This has included the production of unique materials (again made possible due to the lack or gravity) or materials with a greater purity than can be achieved on Earth; energy production and clean energy alternatives. Astronomy and Earth sciences have formed a third leg of ISS science, with the former encompassing wide-ranging stellar and solar studies such as the impact of cosmic rays and the solar wind on out atmosphere, solar observations, research into dark matter, etc. Earth sciences have included climate change studies, monitoring ice melt, global pollution (including world-wide emissions of carbon gases and aerosols, etc.

The fourth aspect of ISS research is education and cultural outreach. This includes teaching and lecturing from orbit, working with Earth-based students by carrying out their experiments, etc. An amateur radio programme gives students from around the world the opportunity to contact the ISS and talk about science, technology, mathematics and engineering with the crew.

Research is split between the various science modules on the station, with some providing unique environments / facilities for specific research fields, others sharing larger research projects. The science programme can additionally be extended or supplemented through equipment and experiments carried up to the ISS via crewed and uncrewed vehicles.

Operating the ISS has not been easy. It is subject to numerous international agreements, has required the involvement of some 17 nations over the years (although Brazil has officially withdrawn from the programme), with 15 nations being original signatories to the ISS Intergovernmental Agreement. A total of 25 individual space agencies and centres around the world have a hand in managing ISS operations from the ground, with Russia and America providing the primary mission control centres and staff. These two countries are also responsible for carrying all crew to / from the station, and for the core missions to keep the station supplied with consumables, fuel, equipment, etc., although Japan also provides re-supply missions as well (as did the Europeans until their Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) programme came to an end).

Given the number of nations involved, there have inevitably been tensions from time-to-time, with perhaps the most famous being in 2009, when a disagreement between America and Russia resulted in Russian mission managers banning US personnel from using the toilets in the Russian modules and forbidding their cosmonauts from using toilets in the US modules!

Outside of odd bouts of tension on the ground, the main challenges in operating the ISS tend to be space-based. Several parts of the station are now ageing (the Zvezda module, whilst launched in 2000, was actually built in the 1980s, for example), so maintenance of the station, inside and out, accounts for a significant about of operational time. Stress on the structure as a whole means that there are often minor pressure / atmosphere leaks – which can be exacerbated by impacts with dust and tiny particles of debris, some of which can grow to be quite serious (but not life-threatening). There’s also the growing risk of collision with large pieces of orbital debris.

However, despite all this, the ISS today continues to be at the forefront of human space research, and can form an essential platform for research into crewed missions to Mars. It is estimated to cost US $7.5 million per crew member per day to operate the station – which, while expensive, is still less than half the anticipated cost set in 2000. Thanks to the US Senate and House finally giving approach, US funding for the station means it can now continue operating through to 2030.