One of the most fascinating places in the entire solar system is Europa, the second innermost of the four Galilean moons of Jupiter, and the smallest – although “smallest” here being a relative term, Europa (diameter around 3,100 km) being only very slightly smaller in size than our own Moon (diameter approx 3,475 km).

As I’ve explained in past Space Sunday pieces, Europa is subject to similar gravitational flexing as seen on Io, the innermost of the four Galilean moons. This flexing, caused by the unequal push-pull of Jupiter’s immense gravity on one side and the unequal yet effectively combined gravitational pull of the other three Galilean moons on the other, has marked Io as the most volcanically active body in the solar system with upwards of 400 active volcanoes marking its surface.

In Europa’s case, the common consensus has been that this flexing is sufficient to cause its core to stretch and contract, generating heat which keeps the waters trapped under the icy crust in a largely liquid state. It has also been hypothesised that this flexing could give rise to ocean floor hydrothermal vents and fumaroles, spewing heat, chemicals and minerals into the ocean; elements which might have kick-started life within Europa’s waters, much as we have seen around similar deep ocean hydrothermal vents here on Earth.

However, there are two stumbling blocks with these ideas. The first is whether or not there is sufficient energy being generated deep within Europa needed to drive a tectonic-like motion in the mantle and cause hydrothermal venting. The second is that, even with the minerals and chemicals blasted out of deep ocean fumaroles here on Earth, our oceans are rich in nutrients vital for life generated by things like the constant death and decay of marine life, the interaction of solar radiation with salts and other minerals within the upper reaches of our oceans, etc., and which are carried down to the depths by the natural cycles present within our oceans and help drive the life processes fund around deep water fumaroles.

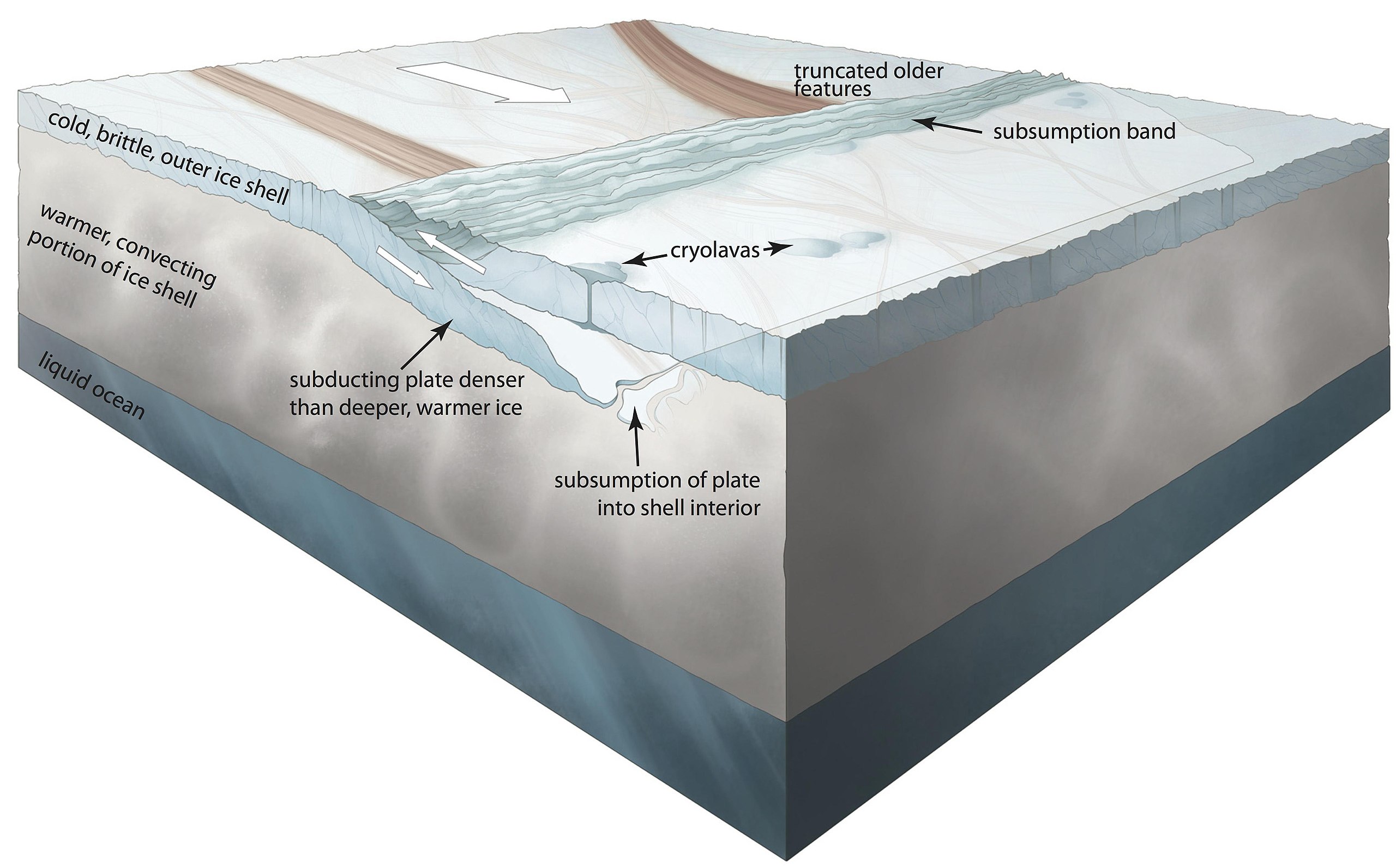

While it is known that Europa has interactions between the intense radiations given off by Jupiter and the salts and minerals in its surface ice (giving rise to the discolouration seen across much of the moon) which likely give rise to chemicals and nutrients, how these might get down through the ice into the ocean below remains a unclear – although one theory suggests subduction might be a suitable mechanism.

A recently published study by geophysicists at Washington State University and Virginia Tech offers a more novel idea: crustal delamination. This is a geological process long known on Earth whereby our planet’s tectonic movement gradually “squeezes” a zone of the planet’s crust, chemically densifying it until it detaches from the crust and sinks into the mantle.

Europa’s icy crust is in a degree of motion thanks to the aforementioned flexing. As noted above, this gives rise to the potential of subduction pushing “plates” of ice under others. Whether or not this is strong enough to push nutrient-laden ice down to the level of the ocean is unclear. However WSU / Virginia Tech study suggests the flexing, breaking and reforming of Europa’s surface ice could result in a unique kind of “crustal delamination”, with their model suggesting it could allow pockets of mineral and nutrient rich ice to “burrow” down to the warm liquid ocean, melt and release their nutrients into Europa’s supposed thermal currents.

If correct, this could allow Europa to provide the kind of nutrients any life down on its ocean floor. What’s more, it’s a theory that works within the subduction model, allowing the two to work together in the supply of nutrients and chemicals into Europa’s waters.

All of which bodes well for the theory that Europa may be an abode for life. However, another study authored by a team of leading planetary science experts concludes that suggests that whilst the competing gravitational forces at work on Europa might be sufficient to cause the moon to flex, but are insufficient to cause any kind of hydrothermal venting on the moon’s ocean floor.

If we could explore that ocean with a remote-control submarine, we predict we wouldn’t see any new fractures, active volcanoes, or plumes of hot water on the seafloor. Geologically, there’s not a lot happening down there. Everything would be quiet.

– Paul Byrne, an associate professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences

This conclusion was reached after taking data on Europa’s size, the likely make-up of its deep core and surrounding mantle, its orbit, and on the likely gravitational forces at work on the moon. In particular, the study also contrasted the orbit of Io with that of Europa, and the role it plays in Io’s extreme volcanism.

Io occupies something of an erratic orbit and this increases the amount of influence gravities of Jupiter and the other three Galilean Moons have on it. But Europa’s orbit is closer to circular, and less prone to gravitational extremes, thus reducing the overall amount of flexing the moon experiences, greatly reducing the likelihood of any internal heating driving the kind of “tectonic”-like shifts in Europa’s mantle needed for venting to occur.

Europa likely has some tidal heating, which is why it’s not completely frozen. And it may have had a lot more heating in the distant past. But we don’t see any volcanoes shooting out of the ice today like we see on Io, and our calculations suggest that the tides aren’t strong enough to drive any sort of significant geologic activity at the seafloor.

– Paul Byrne, an associate professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences

The key point here is that whilst a form of crustal delamination may well be at work alongside subduction to deliver vital nutrients for life deep into the waters of Europa’s oceans, without the hydrothermal venting acting as a direct energy and chemical / mineral source required to give that life a kick-start, the chances are, those nutrients aren’t really helping anything.

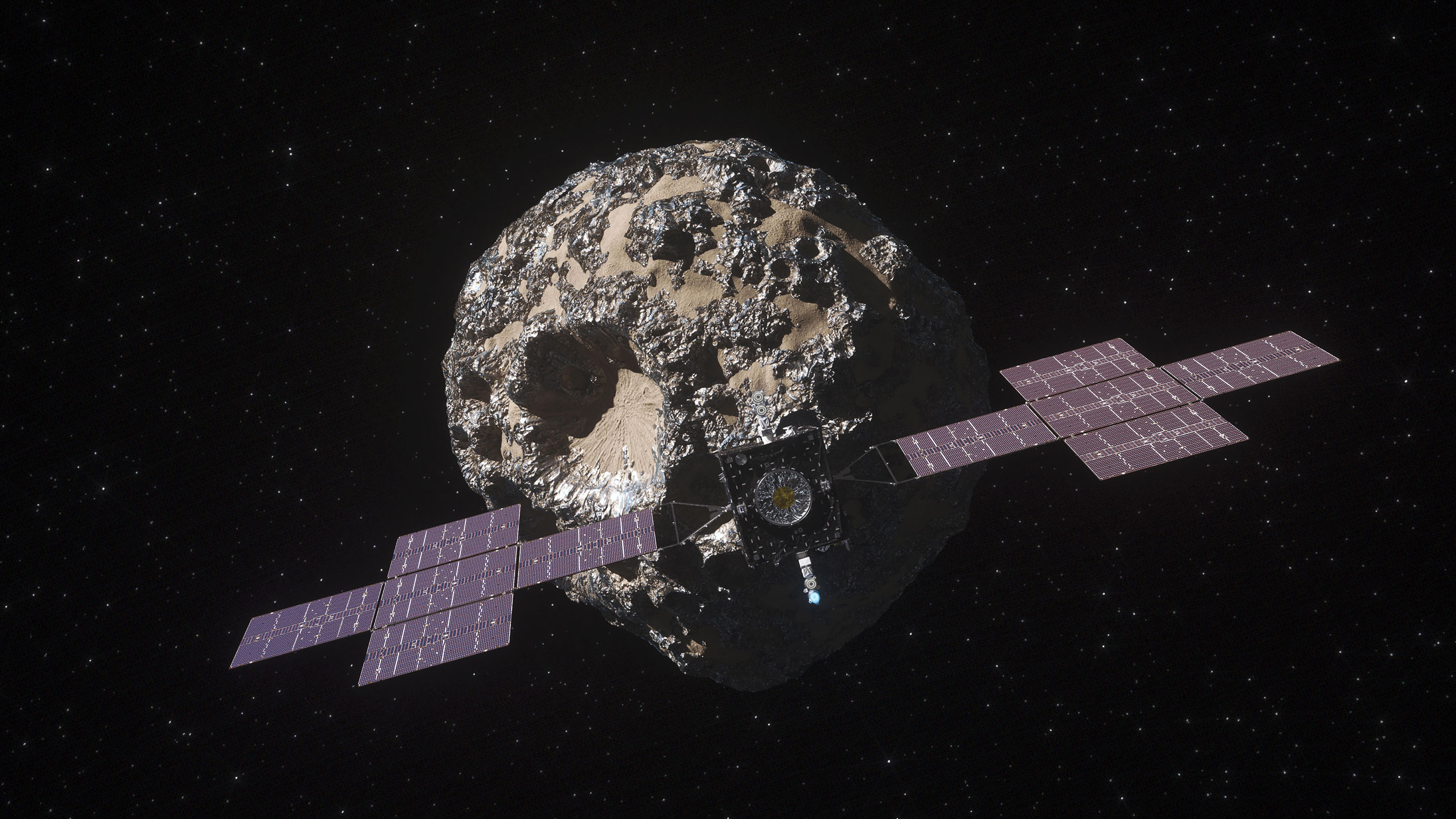

All of which make the discoveries NASA’s Europa Clipper and ESA’s Juice mission might make when they reach the Jovian system in the 2030s and start probing Europa’s secrets in great detail, all the more intriguing.

Blue Origin Confirm NG-3 Mission; Rocket Lab Suffer Neutron Setback

Two missions provisionally set for launch in the first quarter of 2026 received updates both good and bad (and a little curious in the case of one) this week.

The good / curious update came from Blue Origin with the confirmation of the next flight of their New Glenn heavy lift launch vehicle (HLLV). In it, the company indicated they are on course to launch New Glenn on its third flight towards the end of February 2026, and that it will utilise the core booster stage called Never Tell Me The Odds, used in the second flight of New Glenn – NG-2 – which set NASA’s twin ESCApades satellites on their way to Mars. Thus, the mission will be the first to see the re-use of a New Glenn core stage.

The curious element of the announcement lay in the payload for the mission – NG-3. Following NG-2, Blue Origin had indicated they would be looking to launch their Blue Moon Pathfinder mission to the Moon on NG-3, also reusing Never Tell Me The Odds in the process. However, this mission has now been moved back in the company’s launch manifest and, at the time of writing, has no indicated launch period other than “2026”. Instead, NG-3 will launch a 6.1 tonne Bluebird communications satellite to low Earth orbit (LEO) on behalf of AST SpaceMobile, helping to expand that company’s cellular broadband constellation.

Blue Origin has not stated any reason for the payload swap or whether it is due to requiring more time to prepare the Blue Moon demonstrator lander or not. It might be that the company needs more time in preparing Blue Moon, or it might be because they’d rather launch that mission using a new core booster; or it might be because they want to gather more data on vehicle performance carrying heavier payloads. The first two launches carried around 2-3 tonnes and just over a ton respectively. Blue Moon masses almost 22 tonnes, a sizeable jump, whereas Bluebird is a more modest increment.

Meanwhile, Rocket Labs suffered a setback which spells the end of their hopes to debut their Neutron rocket in the first quarter of 2026 – and which might delay the vehicle’s maiden flight by as much as a year.

Neutron is intended to be a 2-stage, partially-reusable medium lift launch vehicle (MLLV) in roughly the same class as ULA’s Vulcan-Centaur and SpaceX’s Falcon 9. However, it is of a highly innovative design, the second stage of the vehicle and its payload being carried aloft inside the first stage, within a set of clamshell payload fairings the company calls the “hungry hippo”. These open once the rocket has cleared the Earth’s denser atmosphere so the payload and its motor stage can be released, the core stage then returning to land on a floating platform.

A video showing the 2025 ground testing of Neutron’s aerodynamic fins, which will be used in the core stage’s descent to a landing barge touchdown, and the “Hungry Hippo” payload fairing forming the nose of the stage

The first Neutron vehicle (sans its upper stage and payload) arrived on the pad at rocket Lab’s launch facilities at the Mid-Atlantic Region Spaceport (MARS) on the Virginia coast earlier in January. On January 21st, the vehicle was undergoing a hydrostatic pressure trial intended to validate structural integrity and safety margins so as to ensure a successful launch. However, during the test, the vehicle’s main propellant tank buckled and then ruptured, effectively writing off the rocket.

Rocket Lab will now need time to analyse precisely what went wrong, why the propellant tank gave way and whether any significant structural alterations need to be made to it prior to any launch attempt being made.

Gazing into the “Eye of Sauron”

Our Sun will one day die. In doing so, its hydrogen depleted, it will swell in size as it struggles to consume progressively heavier elements within itself before it collapses once more, shedding its outer layers into what we call a planetary nebula. It’s not a unique end for a main sequence star such as the Sun, but it can be a beautiful one when viewed from afar and through the eyeglass of time.

One such planetary nebula is that of NGC 7293 / Caldwell 63, commonly referred to as the Helix Nebula. Located some 650 light years away within the constellation of Aquarius as seen from Earth, it is one of the closest bright planetary nebulae to our solar system.

Formed by an intermediate mass star thought to be similar to the Sun, the Nebula takes its name by the fact that the outer layers look – from our perspective, at least – like a helix. Some 2.9 light years across its widest axis, the nebula features the stellar core of the star which created it near its centre, a core so energetic as it collapses towards becoming a white dwarf it blew off, it causes the layers of gas and dust to brightly fluoresce.

This combination of shape and fluorescing colours has given the nebula two additional informal names: The Eye of God, and more latterly and partially in fun in the wake of the Lord of the Rings films, The Eye of Sauron. The nebula was perhaps first made famous by a nine-orbit campaign using the Hubble Space Telescope to capture true-colour images of it in 2004, resulting in a stunning (at the time) composite image of the nebula.

In 2007, the Spitzer Space Telescope captured the Helix Nebula in the infrared wavelengths, revealing much of the complex structure of the nebula’s gas and dust layering, with the core remnants of the star forming it clearly visible and blood red taking to the infrared, giving it the appearance of an eye.

More recently, both the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) VISTA (Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy) wide-angle telescope located high in the Atacama Desert of Chile, and NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) 1.5 million km out in space, have caught the full majesty of the Helix Nebula in comparative detail.

In particular, the JWST images reveal much of the intricate nature of the layers of gas and dust within the nebula. These include clear signs of how the powerful pulses of stellar wind from the dying star are forcing most of the gases and dust in the layers to be pushed away from the core, with globular-like knots and strands of denser material resisting the push, forming what is called cometary knots, due to their resemblance to comets and their tails. However, these “comets” tend to be wider than the planetary core of our solar system!

JWST’s images also reveal the blue heat of stars beyond the nebula diffracted into beautiful star-like forms by the intervening (and invisible) gas and dust. VISTA, meanwhile helps put the JWST images into perspective within the Nebula as a whole. They also demonstrate how it was likely Helix was result of three different outbursts – or epochs – from the star.

The innermost of these epochs is obviously the youngest and more intact and more exposed to the outflow of stellar winds from the star’s remnants, whilst the outermost is interacting with the interstellar medium, with evidence of shockwaves, ripples, and a general “flattening” of the expanding clouds as it collides with the increasingly denser gas within the interstellar medium. This outermost layer was likely formed about 15,000-20,000 years ago, with the innermost about 10,000-12,000 years old.

In time – around 30-50,000 years from now – the Helix Nebula will vanish as it merges into the interstellar medium and its star collapses into a quiescent white dwarf. But for now it continues to turn its eye upon us, gazing down as an entrancing ring of beauty, visible to professional and amateur astronomers alike.