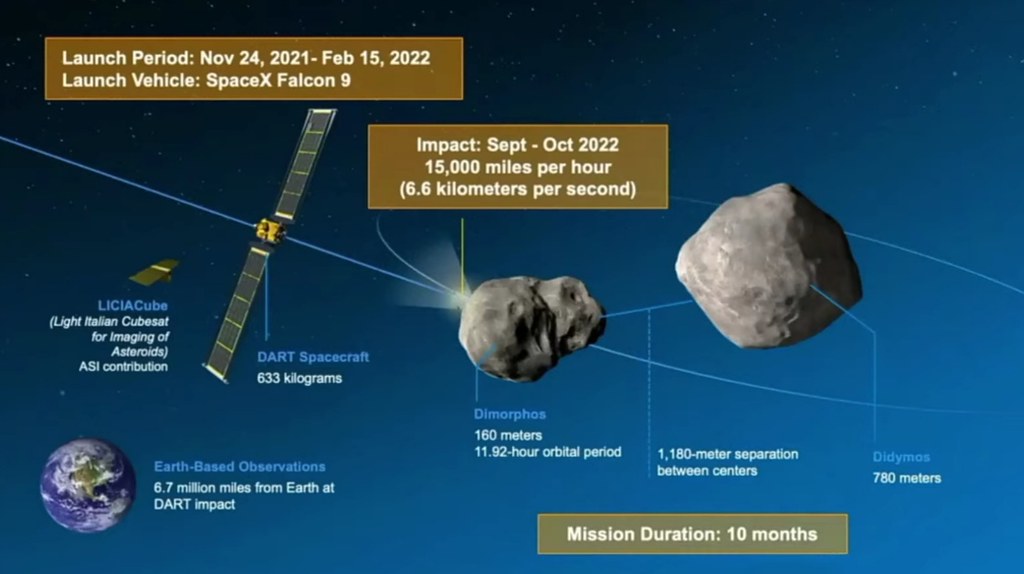

On November 24th, 2021, NASA launched the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission, a vehicle aimed at testing a method of planetary defence against near-Earth objects (NEOs) the pose a real risk of impact.

I’ve covered the risk we face from Earth-crossing NEOs – asteroids and cometary’s fragments that routinely zoom across or graze the Earth’s orbit as they follow their own paths around the Sun. We are currently tracking some 8,000 of these objects to assess the risk of one of them colliding with Earth at some point in the future. This is important, because it is estimated a significant impact can occur roughly every 2,000 years, and we currently don’t have any proven methods of mitigating the threat should it be realised. And that is what DART is all about: demonstrating a potential means of diverting an incoming asteroid threat.

Developed as a joint project between NASA and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), DART is specifically designed to deflect an asteroid purely through its kinetic energy; or to put it another way, by slamming into it, and without breaking it up. Both are important, because by simply slowing an Earth-crossing NEO along its orbit, we give time for Earth to get out of its way; then, by not causing it to break, then we avoid the risk of it becoming a hail of shotgun pellets striking Earth at some point further into the future.

The target for the mission is a binary asteroid 65803 Didymos (Greek for “twin”), comprising a primary asteroid approximately 780 metres across, and a smaller companion called Dimorphos (Greek: “two forms”) caught in a retrograde orbit around it, with both orbiting the Sun every 2 years 1 month, periodically passing relatively close to Earths, as well as periodically grazing that of Mars.

Discovered in 1996 by the Spacewatch sky survey the pair has been categorised as being potentially hazardous at some point in the future. At some 160m across, Dimorphos is in the broad category of size for many of the Earth-crossing objects we have so far located and are tracking, making it an ideal target.

DART actually started as a dual mission in cooperation with the European Space Agency (ESA) called AIDA – Asteroid Impact & Deflection Assessment. This would have seen ESA launch a mission called AIM in December 2020 to rendezvous with Didymos and enter orbit around it in order to study its composition and that of Dimorphos, and to also be in position to observe DART’s arrival in September 2022 and its impact with the smaller asteroid.

However, AIM was ultimately cancelled, leaving NASA to go ahead with DART. To reduce costs, NASA initially looked to make it a secondary payload launch on a commercial rocket. But it was ultimately decided to use a dedicated Falcon 9 launch vehicle for the mission, allowing it to make its September 2022 rendezvous with Dimorphos.

In order to impact the asteroid at a speed sufficient to affect its velocity, DART needs to be under propulsive power. It therefore uses the NEXT ion thruster, a type of solar electric propulsion that will propel it into Dimorphos at a speed of 6.6 km/s – which it is hoped will change the velocity of the asteroid by 0.4 millimetres a second. This may not sound a lot, but in the case of hitting an actual threat whilst it is far enough away from Earth, it is enough to ensure it misses the planet when it crosses our orbit.

This motor is powered by a deployable solar array system first deployed to the International Space Station (ISS). However, what is most interesting about these solar panels is that a portion of them is configured to demonstrate Transformational Solar Array technology that can produce as much as three times more power than current solar array technology and so could be revolutionary should it reach commercial production.

Accompanying DART is Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids (LICIACube), a cubesat developed by the Italian Space Agency, and which will separate from DART 10 days before impact to acquire images of the impact and ejecta as it drifts past the asteroid. To do this, LICIA Cube will use a pair of cameras dubbed LUKE and LEIA.

As the cubesat is unable to orbit Didymos to continue observations, ESA is developing a follow-up mission called Hera, Comprising a primary vehicle bearing the mission’s name, and two cubesats, Milani and Juventas, this mission will launch in 2024, and arrive at the asteroids in 2027, 5 years after DART’s impact, to complete a detailed assessment of the outcome of that mission.

ISS Gets a New Module

On November 26th, 2021, a new Russian module arrived at the International Space Station (ISS).

The Prichal, or “Pier,” module had been launched by a Soyuz 2.1b rocket out of the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan two days earlier. Mounted on a modified Progress cargo vehicle, the module was successfully mated with the Nauka module which itself only arrived at the station in July, at 15:19 UTC.

The four-tonne spherical module has a total of six docking ports, one of which is used to connect it with Nauka, leaving five for other vehicles. However, when first conceived, the module was also intended to be a node for connecting future Russian modules.

But since that time, the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, has abandoned plans to support the ISS with additional modules. Instead, with relations with the west continuing to cool and the ongoing rise in nationalism in Russia, the agency has indicated it plans to orbit its own space station. This being the case, Prichal is viewed as the final element in the Russian segment of ISS, and potentially the first of the new station.

Unlike the arrival of Nauka in July, Prichal managed to dock with the ISS without the additional “excitement” of any thruster mis-firings. Now, the Progress carrier vehicle will remain attached to the module through until December 21st, allowing time for the Russian cosmonauts on the station to carry out a spacewalk to attach Prichal to the station’s power systems. Once it has been detached, the Progress vehicle will be set on a path to burn-up in the Earth’s atmosphere.

As well as expending the docking facilities at the ISS, Prichal delivered some 2.2 tonnes of cargo and supplies to the station. The module will formally commence operations in its primary role in March 2022 with the arrival Soyuz MS-21.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: a DART plus JWST and TRAPPIST-1 updates”