On July 16th, NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity passed the one kilometre mark (0.62 miles) on its travels around Gale Crater. The milestone came eleven months after the one-tonne rover arrived on the surface of Mars on August 5th 2012.

On July 16th, NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity passed the one kilometre mark (0.62 miles) on its travels around Gale Crater. The milestone came eleven months after the one-tonne rover arrived on the surface of Mars on August 5th 2012.

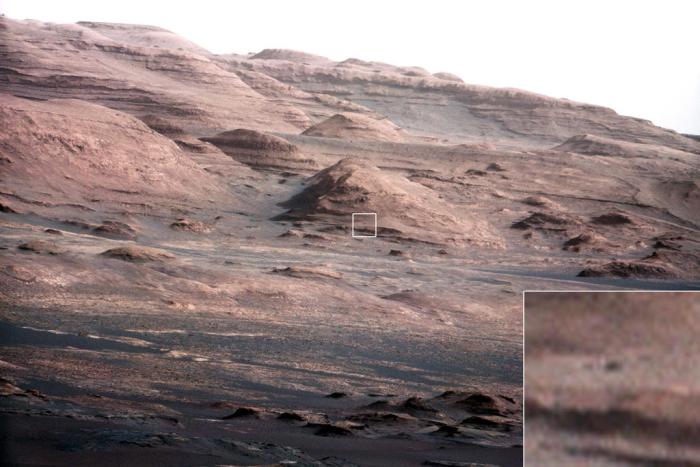

Since that time, Curiosity has achieved a lot; it has travelled across several terrain types, it has studied the Martian atmosphere and meteorology and probed the ground underneath it for evidence of water. It has taken samples from the surface of Mars and drilled into rocks. It has analysed samples and returned a huge amount of data to Earth, including thousands of colour, black and white and high-resolution images. It has viewed its surrounding in 3D and – most intriguing of all – it has discovered very convincing evidence that Mars was more than likely once an abode suitable for the evolution of basic life.

Coincidentally, July 17th 2013 marked the half-way point for the rover’s prime mission of one Martian year (687 day or 1.88 Earth years). As the rover’s power system has a potential operating life of fourteen years, it is more than certain that, barring any accidents or major systems failure in the interim, operations will be extended well beyond the prime mission time frame. In this, Curiosity will not be alone; half a world away, NASA’s rarely mentioned Opportunity rover is fast approaching the tenth anniversary of what was originally a 90 day mission.

More Atmospheric Analysis

As mentioned above, Curiosity has been studying the Martian atmosphere using the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) suite of instruments. SAM has more recently been involved in analysing rock and soil samples collected by the rover’s scoop and drilling system, so it is easy to forget that it can also “sniff” and analyse Martian air, which it did for the very first time right back at the start of the mission. Since then, SAM has continued to periodically sample the Martian atmosphere, and it has already helped in further understanding the dynamics of the atmosphere and how it may have been lost over time.

SAM is able to measure the abundances of different gases and different isotopes in the Martian atmosphere. Isotopes are variants of the same chemical element with different atomic weights due to having different numbers of neutrons. In the first set of tests carried out, SAM compared the stable isotope argon-36 with its heavier cousin, argon-38. Since then, SAM has carried out a series of comparative tests on a range of isotope drawn from the Martian atmosphere, including carbon-12 and carbon-13 and both oxygen and hydrogen isotopes.

These tests, carried out using two different instruments within SAM – the mass spectrometer and tuneable laser spectrometer – during the first 16 weeks of the mission, measured virtually identical ratios of carbon-13 to carbon-12, with the ratios again pointing to the lighter isotopes having “bled off” into space from the upper portions of Mars’ atmosphere, rather than a process of the lower atmosphere interacting with the ground.

“Getting the same result with two very different techniques increased our confidence that there’s no unknown systematic error underlying the measurements,” said Chris Webster of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “The accuracy in these new measurements improves the basis for understanding the atmosphere’s history.”

The rate at which Mars is currently losing its atmosphere cannot be measured by Curiosity or any of the vehicles currently operating in orbit around Mars. This will be the work of the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission, which is due to be launched in November 2013.

Gullies on Mars: Water or Dry Ice?

While it is accepted that Mars’ atmosphere was once dense enough to support liquid water – Curiosity itself has found unmistakable evidence for free-flowing water to have once been present in the crater – evidence has also put forward to suggest that some features imaged on Mars and associated with possible water action may have been the result of another process entirely, as explained in this interesting NASA video.