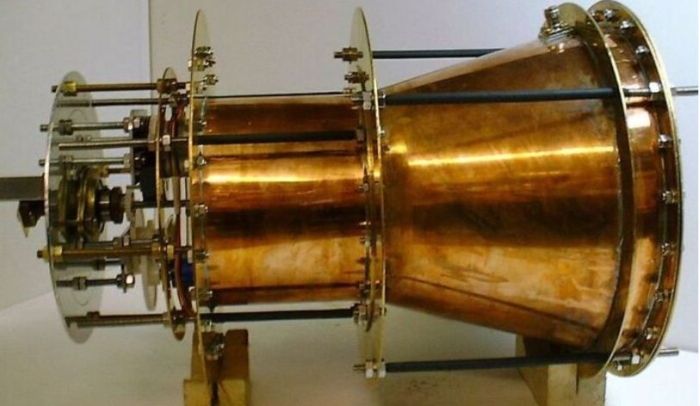

The radio frequency (RF) resonant cavity thruster, or EmDrive (pronounced “M-drive”) as it is more popularly known, has been a source of much controversy since the idea first came into the public eye around 16 years ago, and the debate has been heating up again over the last few months.

First proposed by British engineer Roger Shawyer in 1999, the EmDrive is supposed to be the world’s first working reactionless drive, a means of generating thrust without the use of any propellant. Over the years, it has undergone investigation and testing by a number of organisations and agencies before being quietly pushed aside, while some critics have been publicly scathing of the whole idea, labelling it the “impossible drive” as it violates the fundamental law of conservation of momentum (summed up in Newton’s third law, “for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction”). Even so, research and testing has continued.

The EmDrive supposedly generates thrust by reflecting microwaves between opposite walls of a cone-shaped cavity. In principle, no microwaves or anything else leaves the device, and so it is considered reactionless – although Shawyer states that it isn’t, because the propulsive force is created by a “reaction between the end plates of the waveguide and the Electromagnetic wave propagated within it.”

The attraction of the drive is that were it to work, it could provide an almost endless supply of thrust for satellites and other spacecraft, opening the door to flights to Mars in just 70 days as opposed to the 180-234 days currently required using conventional means. The problem is no-one has actually got the idea to work. Researchers at the at the Northwestern Polytechnical University (NWPU) in Xi’an, China, thought they had in 2012, but further testing in 2014 revealed the thrust apparently created by their EmDrive test rig was actually due to a faulty power connector causing false readings.

Now, however, it seems that a test rig operated by NASA’s Eagleworks Laboratory might actually have demonstrated that in principle an EmDrive could work. News on the testing has actually been leaking out of the laboratory for the past 2-3 months – and has rightfully been met with a healthy dose of scepticism. However, a paper from the team carrying out the research was submitted for peer-review through the Journal of Propulsion and Power, a publication maintained by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) – and is said to have passed muster.

So, does this mean the EmDrive works? Well – no. The peer-review process means that no discernible flaws have been found in the methodology and testing carried out by the Eagleworks team, meriting the idea worthy of further investigation and research. It doesn’t mean fault or error may not yet be found going forward.

One major means of testing the theory of the EmDrive would be to build a working unit and place it in space and see if it works. This is precisely what US engineer Guido Fetta hopes to do. He is planning to place a small version of his Q-Drive (derived from the EmDrive) in orbit for 6 months aboard a CubeSat (between 10×20×30 cm and 12×24×36 cm in size), and then try over six months to manoeuvre the CubeSat using the drive. He’s not alone; China similarly plans an on-orbit test of an EmDrive prototype, although no dates have been specified for them mission.

Did Spirit Find Signature of Past Martian Life?

In January 2004, NASA landed two solar-powered rovers, Spirit and Opportunity on Mars. There primary mission was scheduled to last just 90 days – but Opportunity is still operating today, almost 13 years after it arrived on Mars. Sadly, Spirit was not so lucky; in May 2009, it became stuck in a “sand trap” and unable to free itself, eventually losing power as its solar panels could not be oriented towards the winter Sun on Mars, and falling silent in May 2010.

Nevertheless, Spirit gathered a huge amount of data and images, some of which is being re-examined by scientists Steven Ruff and Jack Farmer from Arizona State University as a result of their field expeditions to Chile – and they believe the rover may have come across evidence for past Martian life.

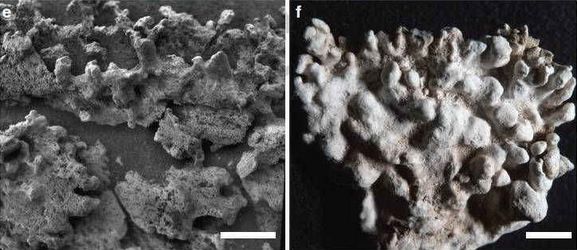

While examining images of a plateau of layered rocks dubbed “Home Plate”, examined by Spirit in 2006, Ruff and Farmer noticed the ground was covered in multiple nodular masses of opaline silica with digitate structures strikingly similar to structures they have encountered within active hot spring/geyser discharge channels at a site in northern Chile called El Tatio.

This is a region which, due a rare combination of high elevation, low precipitation rate, coupled with a high ultraviolet irradiance, is regarded as a potential analogue for past conditions on Mars. What’s more, as a volcanic are, it shares much in common with “Home Plate”, which is believed to be an explosive volcanic deposit created when hot basalt rock came into contact with liquid water. Part of the formation may actually be an extinct Martian fumarole.

The opaline silica Ruff and Farmer found at El Tatio have been shown to be largely of biotic origin; that is, created by microbes. Could this be the same for those Spirit saw at “Home Plate” in 2006? Ruff and Farmer believe it might.

“Although fully abiotic (physical rather than biological) processes are not ruled out for the Martian silica structures, they satisfy an a priori definition of potential biosignatures,” the researchers state in a paper on their work. A biosignature is defined by NASA as “an object, substance and/or pattern that might have a biological origin and thus compels investigators to gather more data before reaching a conclusion as to the presence or absence of life.”

Ruff and Farmer note that while they cannot prove nor disprove a biological origin for the structures imaged by Spirit at “Home Plate”, they should be regarded as a potential biosignature by NASA’s own definition of the term. They go on to state that the only way to be sure would be for a robust examination to be made of the “Home Plate” location, perhaps by NASA’s upcoming Mars 2020, were it to be sent to that region, or through the examination of another region of Mars which is identified as being geographically and geologically similar.

Virgin SpaceShipTwo Flies

Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo vehicle, VSS Unity completed its first free flight test on Saturday, December 3rd, after a month’s delay due to a combination of high winds and an unspecified technical issue, which combined to leave the vehicle able to make just a single captive / carry flight with its carry / launch aircraft, WhiteKightTwo.

The unpowered flight, took place over the Mojave Air and Space Port in California and was the first in a series of around 10 – the precise number will depend on how well the targets for each flight are met – such tests the vehicle will make before Virgin Galactic move to powered flight tests using their new rocket motor for the vehicle, which has so far only been tested on the ground.

“It’s a happy day to be here,” Virgin Galactic’s founder, Sir Richard Branson said just before WhiteKnightTwo lifted SpaceShipTwo aloft. “We’ve got an exciting year ahead, and this is just the start of it.”

As TGO Flexes Its Muscles, More Ice Found on Mars

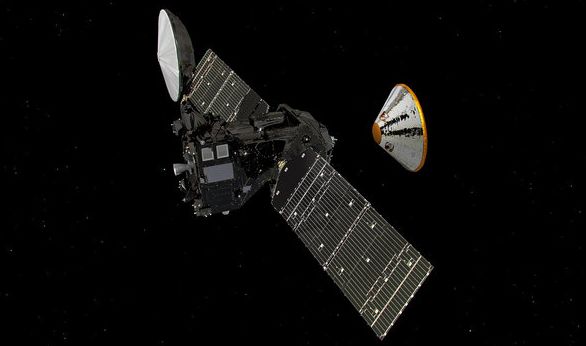

ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), which arrived in orbit around Mars in October, has yet to reach its primary science orbit but it is already flexing its muscles.

On November 22nd, as TGO swept over Mars on one of its current 4.2 day elliptical orbits, a test was carried out on its ability to relay data from the Martian surface to Earth, acting as a go-between for both the Curiosity and Opportunity rovers. As well as carrying a suite of science instruments and camera systems, TGO also carries a communications relay package from NASA called Electra, which allows the spacecraft to successful receive and store communications from NASA’s surface vehicles and then relay them to Earth.

Currently, TGO’s orbit carries it from just 300km (200 mi) above the surface of Mars all the way out to 98,000 km (60,000 mi), limiting its effectiveness as a communications relay. However, this will be lowered and circularised in the coming months to just 400 km (250 mi) above the planet, at which point TGO will be perfectly positioned to carry out its primary science mission and act as a relay for current and future surface missions, including Europe’s own ExoMars rover.

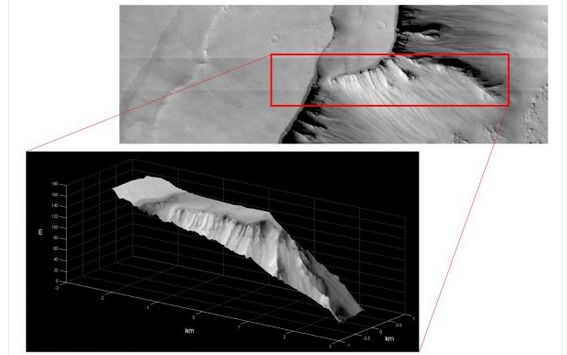

The relay test came at a time when ESA were working on calibrating TGO’s instruments during the close flights over Mars in each of it current orbits around the planet. These calibration tests included initial use of the orbiter’s “eyes”, the Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS), which yielded, in the mission team’s words, “spectacular” results.

CaSSIS is an impressive system, capable of capturing still images and video across a number of colour wavelengths, and in 3D if required. All of CaSSIS’s capabilities were exercised during the test as the orbiter passed over Hebes Chasma, an eight km (5 mi) deep trough just to the north of the mighty Valles Marineris. The images collected during the pass have a resolution of 2.8 metres per pixel. To put that in perspective, it’s the equivalent of flying over New York city at 15,000 km/h (9,375 mph) and simultaneously getting sharp pictures of cars in Philadelphia.

Once TGO reaches its operational orbit towards the end of 2017, CaSSIS will be capable of acquiring 12-20 high-resolution stereo and colour images of selected targets per day.

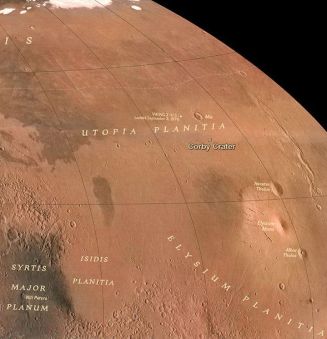

Meanwhile, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (TGO) has located another gigantic water ice deposit lying just under the Martian surface. The ice, lying beneath the planet’s Utopia Planitia, was located using MRO’s ground-penetrating Shallow Radar (SHARAD) instrument.

Estimated to be bigger than the US state of New Mexico and containing more water than Lake Superior, it is the second massive ice deposit SHARAD has found in just over a year. The first exists as a deposition averaging 40 metres (604 ft) think, extending almost all the way from the planet’s mid latitudes up to north polar region and covers an area the size of Texas and California combined.

The ice under Utopia Planitia – the landing site for NASA’s Viking 2 mission of the 1970s – is between 80 to 170 metres (260 feet to 560 ft) in thickness, comprises around 85% water ice (the rest being dirt and other deposits), and – most crucially – lies between 1 and 10 metres (3 and 30 ft) beneath the surface, potentially making it an accessible resource for future human missions to Mars.

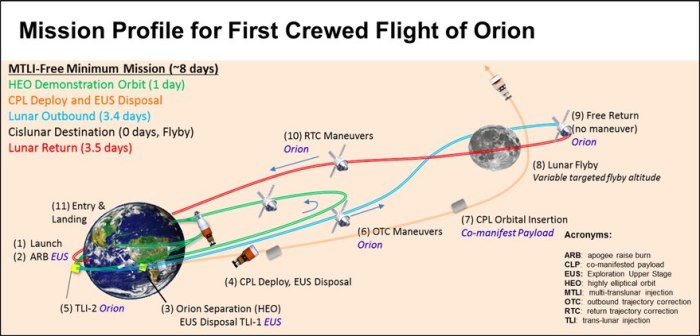

NASA Considering Foreshortening Orion Crewed Flight

NASA is considering a shorter mission for the first crewed flight of its Orion Multi-Purpose Crewed Vehicle.

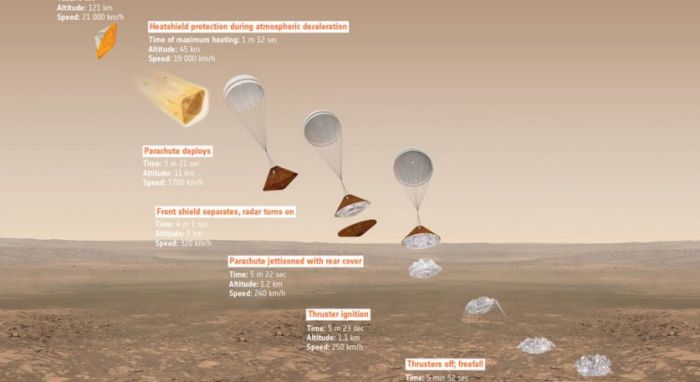

Originally, the flight was to have comprised a “slow cruise” out to the Moon of between 3 and 6 days, followed by three days in lunar orbit before making a similar 3-6 day “slow cruise” back to Earth. However, under the new plans being considered, Orion and its crew would be placed in a high Earth orbit (HEO) with an apogee of 35,000km (21,875 mi), where it would remain for a day, before separating from the Exploration Upper Stage (EUS) of its Space Launch System rocket and suing its Service Module motor to enter a trans-lunar injection orbit, for a single free-return flight around the Moon without ever going into orbit there.

“We’ve effectively designed this mission to be commensurate with the amount of risk we’re taking with crew on the vehicle for the first time,” Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations said when announcing the new plan. “We’ve tailored the mission to be appropriate with the risk we’re willing to take.”

Two particular risks worried mission planners: a failure with the Orion’s life support system in what would be its first space-based test with a crew aboard, or a failure with the Service Module’s engine which might leave them stranded in Lunar orbit. The redesigned mission means the life support system can be tested whilst in HEO, and the service module motor only needs to be fired once, when boosting Orion towards the Moon.

The change in approach does not affect the Exploration Mission 1 flight, scheduled for 2018. That mission is expected to last around 25 days, with an uncrewed Orion vehicle placed in lunar orbit for several days before it returns to Earth. However, it does open the door to a more gradual approach to extending Orion’s capabilities, with NASA now planning one Exploration Mission a year being flown between 2023 and 2030.

Most of these flights will be cislunar operations, with EM-6 (2026) earmarked as the asteroid rendezvous mission originally scheduled to take place in 2023 as EM-3, but which has been pushed back as a result of delays in the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM), its necessary precursor. EM-10 would mark the likely transition from cislunar missions to BEO (“Beyond Earth Orbit”) missions directed towards Mars, utilising Orion and expanded capabilities such as habitat modules and possible nuclear-powered propulsion units.