The International Space Station (ISS) faced further threats from space debris this past week. One December 1st., a planned EVA spacewalk by NASA astronauts Thomas Marshburn and Kayla Barron was pushed back 24 hours over concerns about an unspecified debris threat that might be related to continuing concerns over the recent Russian ASAT missile test that left a cloud of debris orbiting Earth in an orbit that can pass relatively close to the space station.

Then on December 3rd, the ISS had to take more direct action to avoid any risk of collision with a piece of debris designated 39915, a major part of the upper stage of a Pegasus air-launched rocket that flew in 1994, and broke apart two years later.

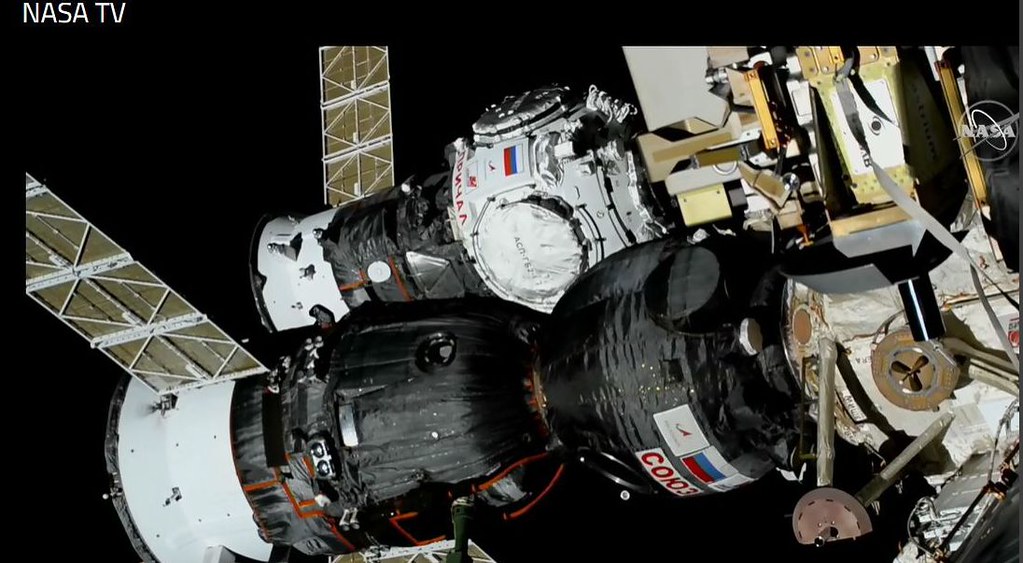

Tracking the debris showed it would come within 5.5 km of the station, so the decision was taken to use the motors of a Progress re-supply vehicle to lower the station’s orbit to increase the clearance between it and the debris.

The motor firing took place at 08:00 UTC on December 3rd, with the thrusters on the Progress vehicle firing for three minutes. The manoeuvre is not expected to impact the December 8th launch of Soyuz MS-20 on Wednesday, December 8th, classified a “space tourism” flight featuring Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa and his assistant, Yozo Hirano on an 18-day trip to the ISS. This will mark the first tourist flight to the space station since 2009. Maezawa is also the name (and money) behind the proposed Dear Moon cislunar mission using a SpaceX Starship vehicle.

All of this excitement blotted the news that NASA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) has warned that NASA and its partners will potentially be without any Earth orbiting space station for a number of years if the ISS is to be “retired” as may currently be the case.

While NASA awarded US $415.6 million to three U.S. groups to develop designs for new orbit “destinations” – commercially-run space stations that can take over from the ISS from 2030 onwards – OIG has stated concerns any of these plans can be realised by that year – seen as the year in which ISS operations are expected to draw to a close.

In particular, the OIG report questions the ability for any commercial space station to be ready by the end of the decade, given the commercial market for on-orbit activities sans government financial support has yet to be assessed, as have the overall costs of developing space station facilities – or even the amount of funding NASA can provide to help ease development along.

In our judgment, even if early design maturation is achieved in 2025 — a challenging prospect in itself — a commercial platform is not likely to be ready until well after 2030. We found that commercial partners agree that NASA’s current timeframe to design and build a human-rated destination platform is unrealistic.

– NASA OIG report on commercial space stations

The report suggests that a further extension to ISS operations to eliminate any gap. However, doing so requires clearing some significant hurdles. The first is that of finance. The Untied States covers more than 50% of the ISS operational budget, and feelings about continuing to support the project beyond 2030 within Congress are very mixed.

There is also the fact that several of the older modules – notably the Russian Zvezda service module – are approaching the end of their operational life. Zvezda in particular has been suffering numerous leaks that have affected overall atmospheric pressure within the station, and numerous fatigue cracks have been located within the module’s structure, not all of which can be fully repaired.

Finally, Russia has indicated it is unwilling to support ISS operations beyond 2030, and is considering using the recently-delivered Prichal module on the ISS as an initial element of that station – although the loss of the module would not necessarily impede ISS operations if no agreement on extending operations beyond 2030 were to be reached.

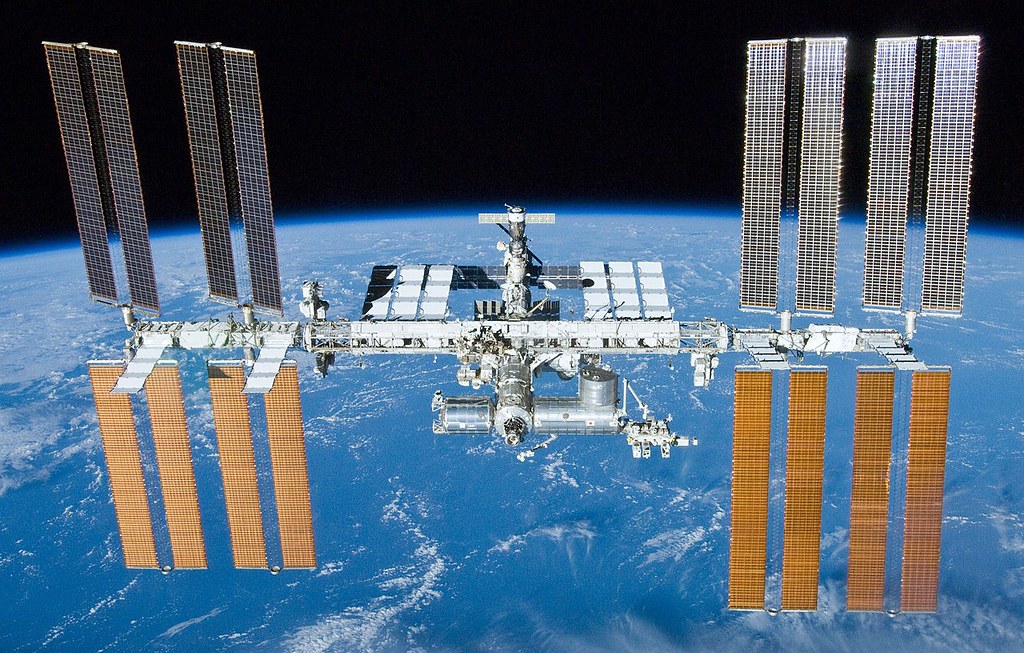

As it is, the ISS has, since 2000, been visited by 403 individual crewed flights that have delivered 250 people to the station, and it remains a remarkable piece of space engineering and construction.

Just how remarkable was again shown in November 2021, when the Crew 2 mission departed the ISS aboard SpaceX Crew Dragon Endeavour; because as they did so, they took a ride around the ISS taking photos that were released this week.

Captured by ESA astronaut Thomas Pesquet, these images reveal the station in great detail – including what appears to be damage caused by what may have been a debris strike on one of the radiator panels.

They also reveal the stunning complexity of the station’s design from the long truss “keel” that is home to the station’s thermal radiator, vital for carrying away heat, and massive primary solar arrays, vital for providing power, to the “international” modules slung “under” it and focused around the US Harmony module, and the “tail” of the Russian built modules with their own solar arrays. In addition the Soyuz, Progress and Cygnus vehicles docked with the station can also be seen in some of the images.

SpaceX and Rocket Lab Updates

SpaceX Gear-Up and Problems

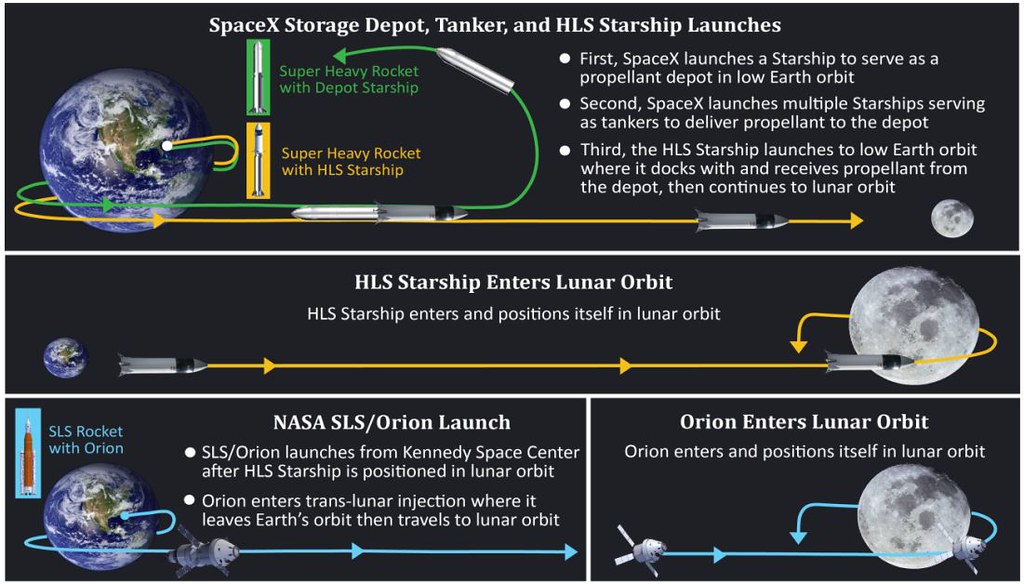

SpaceX is gearing-up for Starship / Super Heavy operations, and also to support further crew flights to / from the ISS.

On Friday, December 3rd, the company indicated it is to resume / start work in earnest on new Starship / Super Heavy launch facilities at Kennedy Space Centre. The new facilities will be at Pad 39A, which SpaceX leased from NASA in 2014 in a 20-year agreement, and which has been the home of Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy vehicles – and will remain so, despite the construction work.

Work on Starship / Super Heavy launch facilities within the Pad 39A launch pad area – home of all but two of the Apollo lunar missions – in 2019, but the work was quickly halted in favour of the work being carried out at the company’s Boca Chica facilities. The plan is to build facilities of a similar nature to those at Boca Chica, but with improvements learned as a result of that work.

The same day as SpaceX confirmed work on the Kennedy Space Centre launch facilities for Starship was resuming, NASA announced it was awarding a further three contracts to SpaceX for crew missions to / from the International Space Station (ISS) in addition to those already assigned to both SpaceX and Boeing, in part as a hedge against Boeing continuing to having issues with their CST-100 Starliner crew vehicle, which has yet to complete its demonstration crewed flight test, now due for some time in 2022.

Neither NASA nor Boeing have issued any update on the status of Starliner since October after valve corrosion problems caused the planned crew flight test to be scrubbed and the vehicle returned to Boeing’s facilities. As such, it appeared unlikely Boeing would gain any additional contracts for ISS flights when NASA issued a request for information in order to award additional contracts for both entire vehicles for dedicated NASA-ISS flights or individual seats on commercial flights. However, this does not preclude them from further contract extensions once Starliner passes certification.

But it is not all good news for SpaceX. The company is encountering issues in scaling-up production of its Raptor engine – vital for the Starship / Super Heavy vehicles. While it is not clear what the problem(s) is / are, the situation appears dire enough for Musk to issue an e-mail to all SpaceX employs that the company could face bankruptcy if the issue(s) is/are overcome.

How serious his warning is, is not clear – he’s issued similar warnings in the past in order to “motivate” staff – and following the e-mail making headlines, he did start stepping back from some of his comments. However, Raptor production is key to the company’s future: SpaceX is banking on a high cadence of Starship / Super Heavy launches each of which will require a minimum of 35 motors per launch – with periodic swap-outs to be expected, even allowing for their reusability. As it is, Musk has indicated he would like to hit 26 launches by the end of 2022, although it is not clear if this is combined booster / Starship launches (using a mix of 35 or 39 motors) or a mix of booster / Starship orbital attempts and further Starship high-altitude flight tests (the latter only requiring 3 or 6 motors).

Rocket Labs Provide Neutron Update

SpaceX aren’t the only contender in the US reusable launch vehicle Market. The New Zealand-US based Rocket Lab is already working towards partial reusability with their Electron small payload launcher, and CEO and founder Peter Beck recently provide an update on their Neutron medium-lift vehicle, which includes an entire new look to the vehicle.

The updated vehicle will be made of carbon composite materials (with Beck taking a slight dig at the use of stainless steel as adopted by SpaceX and (now) Blue Origin), and will be of a tapered design with a 7-metre diameter base. This shape is designed to reduce heat loads during re-entry into the atmosphere, with the booster standing on a set of fixed legs on landing.

Nor does it end there. Neutron’s standard payload to low Earth orbit will be 8 tonnes – marking it as an ideal launcher for the smallsat / constellation / rideshare market. However, this can be extended to 15 tonnes – although this is in a non-reusable format for the vehicle. But perhaps the most unique aspect of the vehicle is the manner in which it carries payloads when operating as a reusable launcher.

Traditional rockets carry their upper stages and payloads on top, with “throw away” aerodynamic fairings protecting the payload through the ascent through the atmosphere. Neutron, however, features fairings that are integrated into the rocket. These will open like petals around the payload / upper stage to allow them to be deployed, then close again to allow the vehicle to maintain the integrity of its shape through the re-entry phase of its flight through to landing.

Overall, the hope is that by using 3D printing, carbon composites, reducing the vehicle mass – which reduces the stress placed on the motor systems – and offering a design with a return to launch site capability that does not require complex infrastructure to enable re-use, Neutron will provide Rocket Lab with a significant launch capability at extremely low, high-competitive pricing.

Assuming the original plans for Neutron remain true, the vehicle’s first flight could come in 2024, most likely utilising the facilities Rocket Lab has been developing at NASA’s Wallops Island, Virginia, launch centre.