The current “race for the Moon” is turning into a hare-and-tortoise situation on several levels, including internationally. On the one hand, there is America’s (arguably over-complicated, thanks to NASA’s insistence on the use of cryogenic propulsion to get to / from the lunar surface) Artemis programme, which seems to race along in fits and bursts (and frequently slams itself into a wall of delay) and then there is China’s more conservative “latter-day Apollo” approach, which quietly plods along, racking up achievements and milestones whilst seeming to be technologically far behind US-led efforts.

As noted, China’s approach to reaching the Moon, is something of a harkening back to the days of Apollo in that it uses a relatively small-scale crewed vehicle for getting between Earth and the Moon, and a similarly small-scale lander. However, size isn’t everything, and both crew vehicle and lander (the latter of which has a cargo variant) would be more than capable in allowing China to establish a modest human presence on the Moon, just as their Tiangong space station, whilst barely 1/4 the size of the International Space Station, has allowed them to do the same in Earth orbit. It is also important to recognise it as part of an integrated, step-by-step lunar programme officially called the Chinese Lunar Exploration Programme (CLEP) and familiarly referenced as the Chang’e Project after the Chinese Goddess of the Moon, which has allowed China to develop both a greater understanding of operations on the Moon and in understanding the Moon itself.

The Chang’e project commenced over 20 years ago, and recorded its first successes in 2007 and 2010 with its Phase 1 orbital robotic missions. This was followed by the Phase II lander / rover missions (Chang’e 3 and Chang’e 4) in 2013 and 2018 respectively, and then the Phase III sample return mission of Chang’e 5 (2020).

Currently, the programme is in its fourth phase, an extensive study of the South Polar Region of the Moon in preparation for human landings, nominally targeting 2030. This phase of the programme has already seen the highly successful Chang’e 6 mission, the first to retrieve surface samples from the Moon’s far side, as well as deploying a rover there. 2026 will see Chang’e 7 launched, a high concept resource seeking mission comprising an orbiter, lander and “lunar flyer”, all geared to locate resources which can be utilised by future missions.

In 2028, the last of the Phase IV mission will launch. Chang’e 8 is intended to be a combination of in-situ resource utilisation (ISRU) test bed, demonstrating how local materials (water ice, regolith) can be used to produce structures on the Moon via advanced 3D printing, and to establish a small ecosystem experiment in advance of human landings.

This approach means that from a standing start, China has replicated much of NASA’s work of the 1960s that helped pave the way for Apollo, but in much greater depth. It’s not unfair to say that by retuning such a focused series of mission phases – notably Phase IV – China potentially will develop a greater spread of knowledge concerning the Moon’s South Polar Region than NASA.

At the same time, China has been developing the hardware required for the human side of the Chang’e Project. This primarily takes the form of their Mengzhou (“Dream Vessel”) reusable crewed vehicle, the Lanyue (“Embracing the Moon”) 2-stage lunar lander / ascent vehicle and the Long March 10 semi-reusable heavy lift launch vehicle (HLLV) offering a very similar capability to Blue Origin’s New Glenn vehicle.

Mengzhou is being developed in two variants: a low Earth orbit (LEO) variant, designed to ferry crews to / from the Tiangong space station. The second is being developed expressly for lunar missions, offering an increased mission endurance capability. The first uncrewed orbital test-flight for the 14-tonne LEO version of Mengzhou is due to take place in 2026, the system having been going through progressive flight tests throughout the 2010 and early 2020s. If successful, it will pave the way for the vehicle to start operating on crewed flights to Tiangong alongside the current Shenzhou craft, which it will eventually replace.

On February 11th, 2026, a test article of the 21-tonne Mengzhou lunar vehicle completed a significant test atop the core reusable stage Long March 10 (Chinese designation CZ-10A) booster. This was a combined mission to test both the Mengzhou launch abort system (LAS) whilst under the rocket’s maximum dynamical pressure flight-regime, and also the booster’s ability to complete an ascent to its nominal stage separation altitude of 105 km, and then make a controlled descent and splashdown close to its recovery ship.

Following a successful launch, the combined vehicle climbed up to the period of “Max Q”, around 1 minute into a flight and wherein the maximum dynamic forces are being applied to the entire stack. The Mengzhou LAS successfully triggered, boosting the vehicle away from the Long March core stage at high speed. The Mengzhou capsule then separated from the LAS performed a splashdown downrange.

During this “glide” phase (actually a controlled descent, the stage orienting itself to fall engines-first), the booster carried out an automated pre-cooling of its engines in readiness for re-use and raise the pressure within the propellant tanks to settle their contents in readiness for engine re-use.

Roughly one minute before splashdown, several of the engines successfully re-lit in a braking manoeuvre to bleed off much of the stage’s velocity. These were quickly reduced to just 3 motors and then a single motor as the stage came to a near-hover before that motor shutdown allowed it to settle smoothly and vertically in the water just 200 metres abeam of its recovery ship.

As an aside, it is interesting to contrast reporting on this flight with media coverage of SpaceX Starship “integrated flight tests”. In the case of the latter, almost every flight has been reported as some kind of spectacular success, despite most of the flights blowing up, barely meeting their assigned goals, or simply re-treading ground already covered. By contrast, the Mengzhou / CZ-10A core stage test flight has largely been defined as a “small step” in China’s progress, with some emphasising the flight “not reaching orbit” – which it was never intended to do.

In reality, the entire flight was a complete success. Not only did it demonstrate the Mengzhou vehicle’s LAS fully capable of lifting the command module and crew clear of an ascending CZ-10A should the latter suffer a malfunction during the most dynamically active phase of it flight, it also further demonstrated the capsule’s parachute descent system and its ability to make a recoverable splashdown (Mengzhou is capable of both water and land-based touchdowns, being able to be equipped with either a floatation device or airbags prior to launch).

Further, the test demonstrated the CZ-10A core stage’s ability to undertake a return to Earth and splashdown (again, the booster is designed to both land on a recovery ship a-la Falcon 9 and New Glenn, or make a splashdown close enough to the recovery ship so it can then be recovered – direct returns to the recovery vessel will be a part of future tests). Finally, such was the accuracy of the guidance systems, the rocket splashed down just 200 metres from the recovery ship, as planned.

That said, it is true that all the core components of the crewed phase of the Chang’e project still have a way to go before China can send a crew to the Moon. But like the tortoise, their one-step-at-a-time / keep-it-simple approach could yet see them become the first nation to do so since 1972.

Why SpaceX is most likely “Shifting from Mars to the Moon”

Thirteen months ago, in an attempt to bolster his failing “Mars colony plan” (a totally unrealistic fever dream of sending a “Battlestar Galactica” scale feet of 1,000 Starship vehicles carrying 1 million people to Mars to establish a colony there), the SpaceX CEO declared “the Moon is a distraction” and Mars was the focus for his company.

Well, he’s had 13 months to forget all that, as on the weekend of February 7th and 8th, 2026, the self-styled man who “knows more about manufacturing than anyone else alive on Earth” and yet cannot deliver on a single one of his manufacturing promises, declared that the Moon is now the focus of SpaceX’s endeavours, all as a part of a grand plan to “expand human consciousness and support his equally questionable idea of operating a 1-million strong constellation of Starlink satellites as a string of “data centres in space”. For good measure he mixes in terms such as “climbing the Kardashev scale” )the latter seems to be a particular reference point for so-called space entrepreneurs of late).

However, the real reason is liable to be far more mundane: the SpaceX CEO is again trying to justify the US $1.2 trillion valuation he and his fellow broad members arbitrarily awarded the company in January, and to justify such a figure in the face of an upcoming IPO whilst also possibly trying to further dazzle investors with shiny promises about orbital data centres and moon bases at a time when SpaceX has just “inherited”xAI and its cash burn-through of around US $1 billion a month.

The promise of a fully operational “Moon Base Alpha” (yes, once again we have a sci-fi trope to add gloss to an idea) in “10 years” will, undoubtedly go the same way as the more than a decade old claim that Tesla vehicles will be capable of full self driving “next year”; the statement that SpaceX would have Starship operational by 2022, and that Starship would fly around the Moon in 2023 and to Mars in 2024, err, 2026, err, 2028. That is to say, most likely never.

Martian Organics Cannot be Entirely Explained by Non-organic Processes

One of the major mysteries of Mars is the question of methane. It was first detected in more than faint trace amounts by the European Space Agency’s Mars Express mission in 2004. A decade later, NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover Curiosity, detected methane spikes and organic molecules whilst exploring the floor of Gale Crater. Then in 2019, the rover a massive spike as it explored “Teal Ridge”, a formation of bedrock and deposits on “Mount Sharp” (Aeolis Mons).

Alongside of this is the vexing discovery of organic elements on Mars. These and the methane seem to point a finger towards the idea that the planet may have once harboured life. However, as even proponents of this idea point out, both organics and methane can result from purely inorganic interactions. The tick is – how to determine which might be the case.

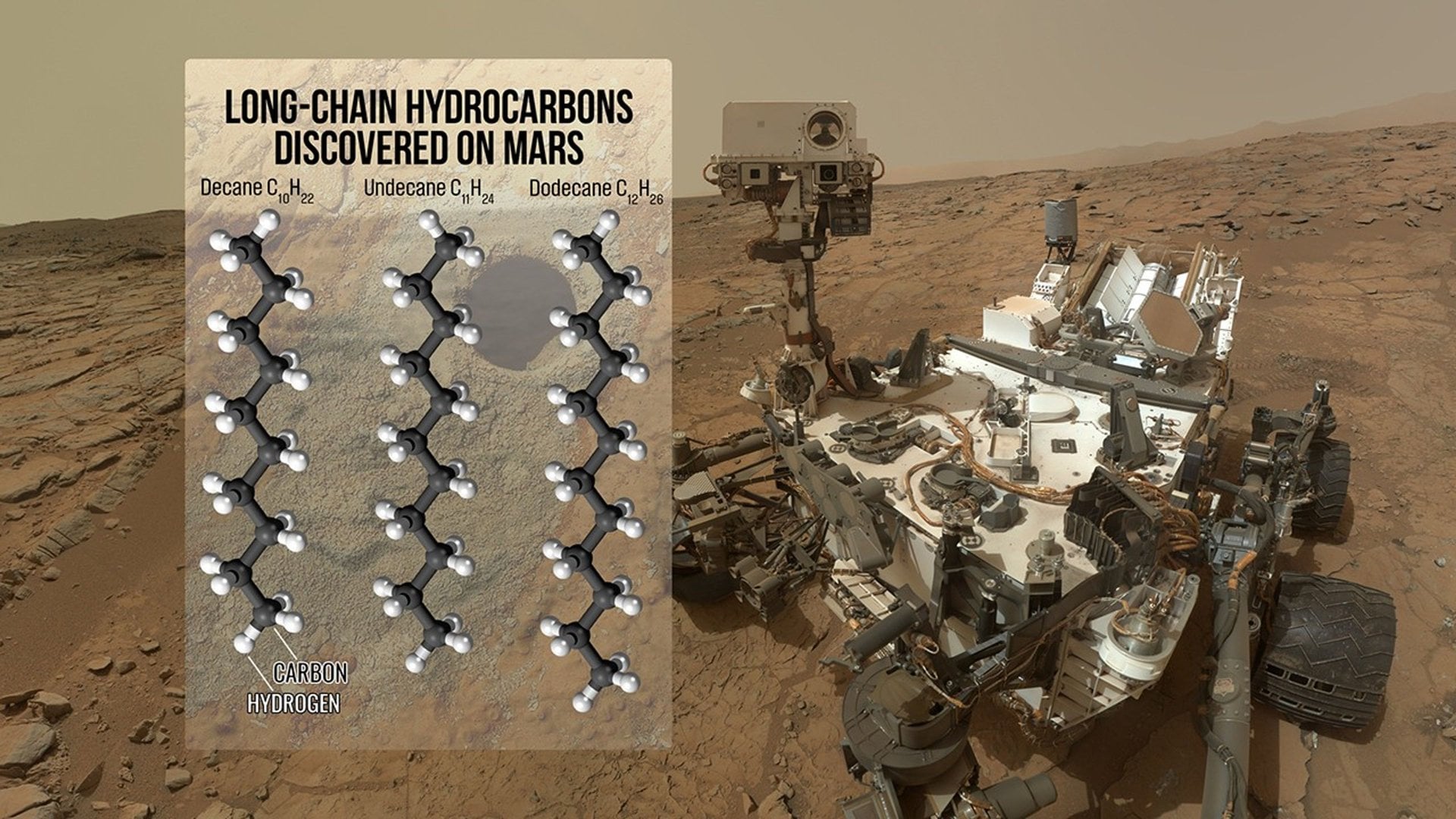

In March 2025, Curiosity detected small amounts of decane, undecane, and dodecane in a rock sample, which constituted the largest organic compounds found on Mars to date. These offered the potential to determine which option might be more likely to cause their existence – organics or inorganic chemical reactions. All three are hydrocarbons could be fragments of fatty acids, also known as carboxylic acid.

On Earth, carboxylic acid (aka fatty acids) is a natural by-product of life. Such acid can be found in animal tissues, nuts and seeds. In the case of animal tissues, carboxylic acid is predominantly formed by the breakdown of carbohydrates by the liver and found within adipose tissue, and the mammary glands. however, they can also be created by inorganic reactions – such as lightning striking chemically rich soils (or regolith), hydrothermal interactions and photochemical reactions between ultraviolet radiation and hydrocarbon-rich mixtures.

In order to try to determine whether the fatty acids discovered by Curiosity preserved in ancient mudstone are the result of organic processes or inorganic. Whilst limited with working only with data from the rover’s Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) spectrometer, the team sought to recreate the likely conditions on Mars some 80 million years ago – this being the amount of time the rock containing the acids would likely have been exposed to the surface atmosphere – and then work back from there to try to determine which would survive the longest: carboxylic acid produced by organic or inorganic means.

What they found was that organic mechanisms appear to leave far more in the way of organic remnants – such as decane, undecane, and dodecane – than the typical non-biological processes involved in forming carboxylic acid could produce. The team suggest that this might be because any organics responsible for the fatty acids might have been assisted by periodic impacts by carbonaceous meteorites, known to be sources of fatty acids formed in space.

However the team also urge caution: whilst their finding might move the needle further towards the idea that Mars once harboured life, they also clearly note that there is a need for greater study; Mars is a complex world, rich in complex interactions. As such, more and detailed study is required – preferably first-hand, through the obtaining of samples from Mars itself. Currently, and rather ironically, whilst NASA had planned to make samples from the Mars 2020 rover Perseverance available for return to Earth, these do not contain samples of a similar nature to those found by Curiosity.

More particularly, at the time Perseverance had launched to Mars with sample retrieval in mind, no-one had actually sorted out how such a retrieval might be achieved. As such, a series of highly complicated, overly expensive proposals were put forward, involving both US and European co-operation. Each of these were knocked down on the basis of complexity and escalating price – up to US $11 billion – or close to half of NASA’s overall budget – for such a mission was just too big an ask. Thus, despite more cost-effective proposals such has Rocket Lab’s (still complex) three-launch mission slated to cost a “mere” US $4 billion, the entire idea of a sample return mission has been cancelled as a result of NASA’s budget being tightened.