What has long been suspected has likely now confirmed: water is present under the ice of Jupiter’s moon Europa.

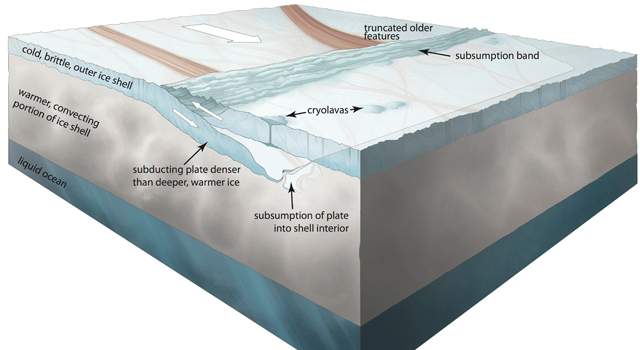

As I’ve noted on numerous occasions in this space Sunday articles, it’s long been thought that an ocean of water exists under the cracked icy crust of Europa, potentially kept liquid by tidal forces created by the moon being constantly “flexed” by the competing gravities of Jupiter and the other large Moons pulling on it, thus generating large amounts of heat deep within its core – heat sufficient to keep an ocean possibly tens of kilometres deep in a liquid state.

Circumstantial evidence for this water has already been found:

- During its time studying the Jovian system between 1995 and 2003, NASA’s Galileo probe detected perturbations in Jupiter’s magnetic field near Europa – perturbations scientists attributed to a salty ocean under the moon’s frozen surface, since a salty ocean can conduct electricity.

- In 2012 the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) captured an image of Europa showing what appeared to be a plume of water vapour rising from one of the many cracks in Europa’s surface – crack themselves pointed to as evidence of the tidal flexing mentioned above. The plume rose some 200 km from the moon.

- In 2014, HST captured images of a similar plume rising some 160 km above Europa.

Now a new paper, A measurement of water vapour amid a largely quiescent environment on Europa, published on November 18th, 2019 in Nature, offers the first direct evidence that water is indeed present on Europa. Specifically, the team behind the study, led by US planetary scientist Lucas Paganini, claims to have confirmed the existence of water vapour on the surface of the moon.

Essential chemical elements (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur) and sources of energy, two of three requirements for life, are found all over the solar system. But the third — liquid water — is somewhat hard to find beyond Earth. While scientists have not yet detected liquid water directly, we’ve found the next best thing: water in vapour form.

– Lucas Paganini

Using the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, Paganini and his team studied Europa over a total of 17 nights between 2016 and 2017. Using the telescope’s spectrograph, they looked for the specific frequencies of infra-red light given off by water when it interacts with solar radiation. When observing Europa’s leading hemisphere as it orbits Jupiter, the team found those signals, estimating that they’d discovered sufficient water vapour to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool in a matter of minutes. However, the discovery has been somewhat tempered by the fact water may only be released relatively infrequently.

Such infrequent releases help explain why it has taken so long to confirm the existence above Europa, but there are other reasons as well. The components that comprise water have long been known to exist on the moon whether or not they indicate the presence of water. Thus, detecting these components within a plume doesn’t necessarily equate to the discovery of water vapour – not unless they are in the right combinations. There’s a further pair of complications in that none of our orbital capabilities are specifically designed to seek signs of water within the atmospheres of the other planets or expelled from icy moons. So Earth-based instruments – like the Keck telescope spectrographs – must be used, and these deal with the naturally occurring water vapour in our own atmosphere.

Within Paganini’s team there is confidence that their findings are correct, as they diligently perform a number of checks and tests to remove possible contamination of their data by Earth-based water vapour. Even so, they are the first to acknowledge that close-up, direct studies of Europa are required – particularly to ascertain if any water under the surface of Europa does form a globe-spanning ocean, or if it is confined to reservoirs or fully liquid water trapped within an icy, slushly mantle. It is hoped that NASA’s Europa Clipper and Europe’s JUICE mission (both of which I’ve “previewed” in Space Sunday: to explore Europa, August 2019) will help address questions like this.

Starship Mk 1 Ruptures its Tanks

As regulars to this column know, I’ve been following the SpaceX Starship development, which has been proceeding a-pace. However, on November 20th, 2019, the programme suffered something of a set-back in plans to have the “Starship Mk 1” vehicle, based that the SpaceX facilities in Boca Chica, Texas, undertake a test flight to an altitude of 20 km before the end of the year.

As a part of the preparations for the flight, SpaceX has been carrying out pressurisation tests on the vehicle’s fuel tanks to confirm their structural integrity. These tests involved filling them with suitable liquids – likely liquid nitrogen and liquid oxygen – to simulate the super-cold fuel loads they are expected to handle during a launch and flight. For these tests, the nose section of the vehicle was removed, and for the first test, carried out earlier in the week, everything went according to plan, with both tanks successfully pressurised and then drained.

However, in the November 20th, 2019 test, the upper and lower bulkheads on one of the tanks ruptured within seconds of each other, causing a massive eruption of cryogenic gas across the test stand, and causing damage to the upper and lower ends of the vehicle’s hull, although it was not destroyed.

In film of the incident, the top bulkhead can be seen flying away from the vehicle as it fails under the tank’s internal pressure. SpaceX recovered it for analysis and issued a statement to confirm no-one was injured during the test, and that they do not regard it as a “serious” setback.

A second vehicle – Starship Mk 2 – is under construction in Florida. However on Twitter, Musk indicated the company will now most likely move ahead with an improved Mk 3 design, which he described as having a “quite different” flight design, and which is due to be constructed at Boca Chica.

SNC Reveals Dream Chaser’s Shooting Star

Another upcoming vehicle I’ve covered in these pages is Sierra Nevada Corporation’s Dream Chaser Cargo, an uncrewed version of their orbital space plane originally conceived to fly crews back and forth between Earth and the International Space Station.

In this cargo role, the space plane will fly uncrewed, with the ability to lift around 5.5 tonnes of cargo and supplies to orbit. Around one tonne of this will be carried inside the vehicle itself, with a further 4.5 tonnes intended to be carried in and on a special cargo module attached to the rear of the vehicle. On November 19th, 2019, SNC unveiled a test mock-up of the module, and revealed its official name: Shooting Star.

The module, which will also supply electrical power to the Dream Chaser, can carry pressurised cargo within in, and up to three tonnes of unpressurised cargo in units mounted against it. The module is some 4.6m in length, and as well as lifting cargo to the ISS, it can be used to dispose of around three tonnes of waste from the ISS, which will burn-up in the Earth’s atmosphere when it is ejected by Dream Chaser as it makes its way back to a runway landing on Earth.

The first flight of Dream Chaser Cargo is scheduled for 2021.

Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner Moves to Launch Complex

One of the two new launch vehicles that will take on the role of flying astronauts too and from the ISS, Boeing Corporation’s CST-100 Starliner capsule, took a major step towards its first uncrewed test flight on November 21st, 2019. This saw the first flight-capable version of the vehicle moved from Boeing’s fabrication facility at Kennedy Space Centre to Launch Complex 41 at the neighbouring Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. At the complex, it is to be mated to its United Launch Alliance (ULA) Atlas V launch vehicle in preparation for a December 17th, 2019 launch.

This first flight of the vehicle will test each stage of a typical astronaut journey, including docking and undocking with the space station itself. Originally scheduled for earlier in 2019, the launch date has slipped twice – first to August 2019, and then to December 2019 – as a result of concerns about the vehicle’s development and readiness to fly.

However, the system cleared its last major hurdle – a launch pad abort test designed to vet the spacecraft’s ability to carry astronauts safely away from any catastrophic failure with its launch vehicle during its initial ascent to orbit – on November 4th, 2019.

If the 8-day text flight is successful, the Starliner will join SpaceX’s Crew Dragon in being ready to complete a crewed test flight to / from the ISS. Both are expected to do so in 2020.

Space Photos for the Week

A Sky Full of Stars

The Milky Way glistens above the Visible and Infra-red Survey Telescope for Astronomy (VISTA) at the Paranal Observatory in northern Chile. Located on a rocky mountaintop in the Atacama Desert, VISTA is the world’s largest telescope built to survey the sky in near-infra-red light. While its surroundings are barren, VISTA’s altitude and surroundings are ideal for astronomy, with almost no cloud cover or light pollution to soil the view.

Apollo 12 Remembered

November 1969 saw the second Apollo mission to the lunar surface, comprising the crew of Charles “Pete” Conrad, Richard Gordon and Alan Bean. In this photograph, mission commander Conrad takes a photograph of Lunar Module Pilot Bean as he goes about his work with his sun visor lowered against the glare of the Sun. As a result, Conrad can be seen reflected in Bean’s helmet visor as he takes the picture with the Hasselblad camera mounted on the chest of his space suit.