After six months in “Yellowknife Bay”, Curiosity is getting ready to move on. Investigations in the area are due to come to an end in the near future, and with the new autonomous driving software now installed in the rover, it is anticipated that the long drive to “Mount Sharp” will begin very soon. The start of this phase of the mission will be marked by the Rover retracing its steps (tracks?) through “Glenelg”, the region so-named partially because it is a palindrome, reflecting the fact the rover would be driving through it twice.

After six months in “Yellowknife Bay”, Curiosity is getting ready to move on. Investigations in the area are due to come to an end in the near future, and with the new autonomous driving software now installed in the rover, it is anticipated that the long drive to “Mount Sharp” will begin very soon. The start of this phase of the mission will be marked by the Rover retracing its steps (tracks?) through “Glenelg”, the region so-named partially because it is a palindrome, reflecting the fact the rover would be driving through it twice.

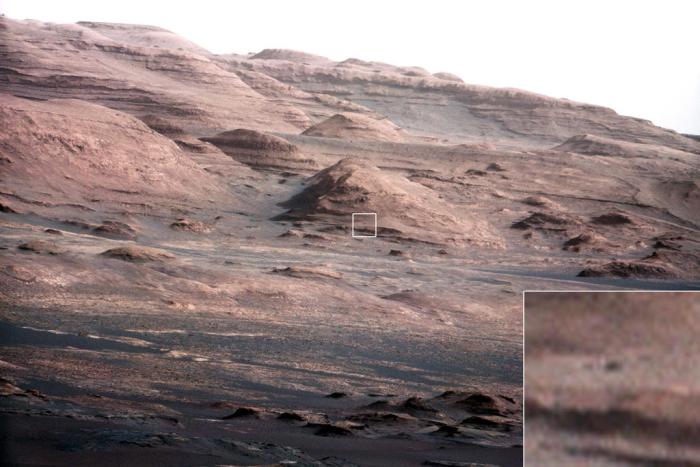

How long the rover will take to get to “Mount Sharp” is entirely open to question, however. While Curiosity is now far more capable of autonomous navigation, it won’t be a case of “pick and route which looks good and go”. If nothing else, there is no way of knowing what the rover might discover while en route.

“We don’t know when we’ll get to Mount Sharp,” Mars Science Laboratory Project Manager Jim Erickson said at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “This truly is a mission of exploration, so just because our end goal is Mount Sharp doesn’t mean we’re not going to investigate interesting features along the way.”

In May, Curiosity completed a second drilling operation to obtain samples from inside an area of bedrock called “Cumberland” within “Yellowknife Bay”, delivering them to the Chemistry and Minerology (CheMin) and Sample Analysis at Mars SAM) suites of instruments aboard the rover for detailed analysis. This work is still ongoing, and it is hoped that the result will further confirm findings obtained as a result of the first drilling operation, carried out a few metres away on a rock formation dubbed “John Klein”, and which suggested that the area once had environmental conditions favourable for microbial life.

No further drilling operations are now planned for the area, although NASA has yet to give word on the results from the initial analysis of the “Cumberland” cuttings. Additionally, once the order is given to start the drive towards “Mount Sharp”, the rover will retain cuttings from the “Cumberland” drilling ins its sample scoop which can be delivered to CheMin and SAM for additional analysis, if required.

Both drilling operations have been important steps for the MSL mission. Not only have they been a successful test / use of the last remain major science capability on the rover (the ability to drill into rocks and obtain samples), they’ve also been an important learning situation for mission engineers. Steps which each took a day each to complete when drilling at “John Klein” could be strung together into a single sequence of commands at “Cumberland”, allowing the rover to complete a number of drilling-related tasks autonomously and in a single day.

“We used the experience and lessons from our first drilling campaign, as well as new cached sample capabilities, to do the second drill campaign far more efficiently,” said sampling activity lead Joe Melko of JPL. “In addition, we increased use of the rover’s autonomous self-protection. This allowed more activities to be strung together before the ground team had to check in on the rover.”

It’s hoped that these capabilities will allow the mission team to plan future routines for the rover more efficiently and in the knowledge that Curiosity has the ability to carry out multiple tasks without the need to “‘phone home” at each stage of an operation, something which introduces considerable delays in activities as a result of the two-way communications lag.

Prior to leaving “Yellowknife Bay”, two further “targets of opportunity” will be subject to brief observations by Curiosity. The first of these is a layered outcrop dubbed “Shaler”, which was briefly looked at as the rover initially entered the “Glenelg” / “Yellowknife Bay” region, and a pitted outcrop called “Point Lake”

The science team has chosen three targets for brief observations before Curiosity leaves the Glenelg area: the boundary between bedrock areas of mudstone and sandstone, a layered outcrop called “Shaler”, a possible river deposit, and a pitted outcrop called “Point Lake”, a depressional area thought to be either volcanic or sedimentary in nature, and which the rover observed when entering “Yellowknife Bay” from “Glenelg”.