I n what has been something of a surprise to scientists around the world, findings from the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) suggest the amounts of methane present in the Martian atmosphere, at least at near-ground levels, are at best negligible.

n what has been something of a surprise to scientists around the world, findings from the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) suggest the amounts of methane present in the Martian atmosphere, at least at near-ground levels, are at best negligible.

While it can be produced by non-organic, as well as organic means, methane has long been regarded as one of the tell-tale signs that life may have once existed on Mars – or even may still exist somewhere beneath the planet’s arid surface.

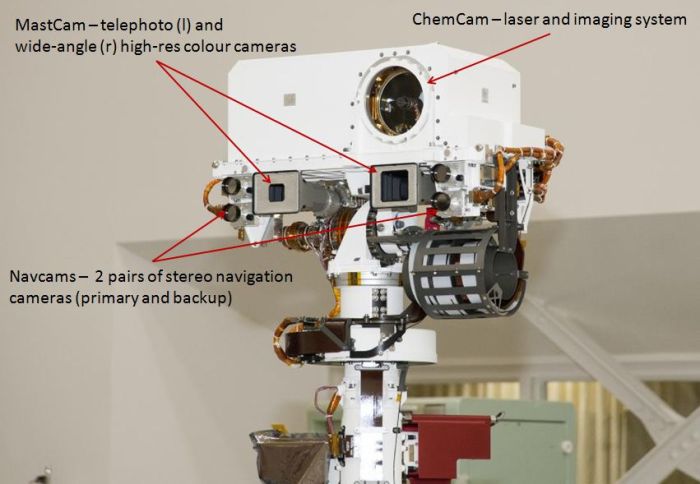

Using the highly sensitive Tunable Laser Spectrometer, a part of the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) science package aboard Curiosity, MSL has subjected six samples of the atmosphere gathered between October 2012 and June 2013 to analysis – and failed to detect any signs of methane, trace or otherwise.

This has come as a surprise because previous data gathered by US and international scientists via a range of means have suggested that while not present in abundant amounts, methane is very detectable within the Martian atmosphere. So much so that some of those involved in MSL were extremely confident ahead of the mission that the rover would find clear evidence of the gas as a part of its analysis of atmospheric samples.

Europe’s Mars Express, for example, which started on-orbit operations in 2004, and is still functioning today, found strong evidence for methane within the atmosphere of Mars. Not long after this, NASA’s own Mars Global Surveyor (the precursor to the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter which relays communications between Curiosity and Earth today), which operated in Mars orbit from September 1997 through to November 2006, also detected methane to a point where scientists where able to map its annual ebb and flow.

On Earth, methane (CH4) is largely the by-product of two distinct activities: geological, such as through volcanic eruptions – and Mars certainly has a fair few volcanoes, some of the largest in the solar system in fact; and via organic means. Either way, it tends to break down relatively quickly, so even trace amounts of it within Mars’ atmosphere suggest that it is being renewed somehow. Given that an erupting volcano on Mars is a tad hard to miss (see “some of the largest in the solar system”, above), a renewable source of methane has seen as evidence that either there is some as yet unknown chemical reaction going-on to create methane – or it may just be the result of outgassing from Martian microbes.

The amount of methane in the Martian atmosphere has never been particularly high; even the best analyses over the years have placed it at a peak of around 70 parts per billion, However, the TLS on Curiosity is a very sensitive piece of equipment. So sensitive that any trace amounts of methane in the Martian atmosphere must be below 1.3 parts per billion (around 10,000 tonnes in total throughout the atmosphere) in order for the TLS to miss it.

Responding to the findings, published on Thursday September 19th in Science Express, NASA has pointed out that the chances of future missions finding evidence of microbial life on Mars, past or present, aren’t entirely dashed. “This important result will help direct our efforts to examine the possibility of life on Mars,” Michael Meyer, NASA’s lead scientist for Mars exploration, said in a press release accompanying the report’s publication. “It reduces the probability of current methane-producing Martian microbes, but this addresses only one type of microbial metabolism. As we know, there are many types of terrestrial microbes that don’t generate methane.”