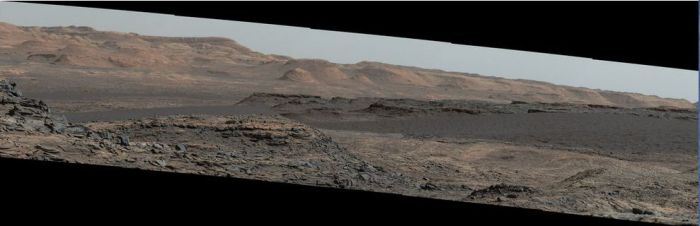

The Mars Science Laboratory rover, Curiosity, continues to climb the flank of “Mount Sharp” (formal name: Aeolis Mons), the giant mount of deposited material occupying the central region of Gale Crater around the original impact peak. For the last three weeks it has been making its way slowly towards the next point of scientific interest and a new challenge – a major field of sand dunes.

The Mars Science Laboratory rover, Curiosity, continues to climb the flank of “Mount Sharp” (formal name: Aeolis Mons), the giant mount of deposited material occupying the central region of Gale Crater around the original impact peak. For the last three weeks it has been making its way slowly towards the next point of scientific interest and a new challenge – a major field of sand dunes.

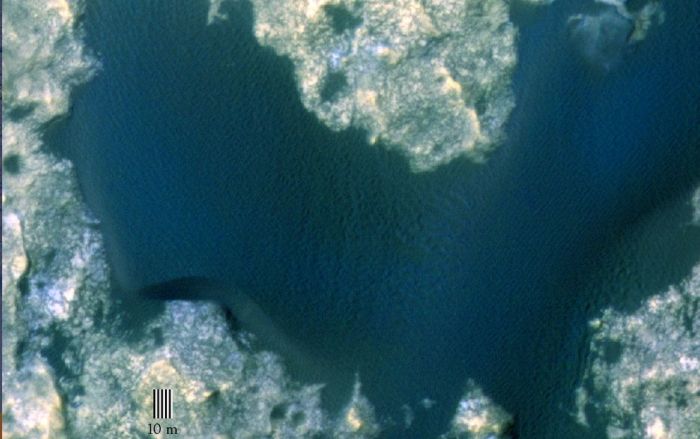

Dubbed the “Bagnold Dunes”, the field occupies a region on the north-west flank of “Mount Sharp”, and are referred to as an “active” field as they moving (“migrating” as the scientists prefer to call it) down the slops of the mound at a rate of about one metre per year as a result of both wind action and the fact they are on a slope.

Curiosity has covered about half the distance between its last area of major study and sample gathering and the first of the sand dunes, simply dubbed “Dune 1”. During the drive, the rover has been analysing the samples of rock obtained from its last two drilling excursions and returning the data to Earth, as well as undertaking studies of the dune field itself in preparation for the upcoming excursion onto the sand-like surface.

While both Curiosity and, before it, the MER rovers Opportunity and Spirit have travelled over very small sand fields and sand ripples on Mars, those excursions have been nothing like the one on which Curiosity is about to embark; the dunes in this field are huge. “Dune 1”, for example, roughly covers the area of an American football field and is equal in height to a 2-storey building.

While the rover will not actually be climbing up the dune, it will be traversing the sand-like material from which it is formed and gathering samples using the robot arm scoop. This is liable to be a cautious operation, at least until the mission team are confident about traversing parts of the dune field – when Curiosity has encountered Martian sand in the past, it has not always found favour; wheel slippage and soft surfaces have forced a retreat from some sandy areas the rover has tried to cross.

Study of the dunes will help the science team better interpret the composition of sandstone layers made from dunes that turned into rock long ago, and also understand how wind action my be influencing mineral deposits and accumulation across Mars.

On Earth, the study of sand dune formation and motion, a field pioneered by British military engineer Ralph Bagnold – for whom the Martian dune field is named – did much to further the understanding of mineral movements and transport by wind action. Understanding how this might occur on Mars is important in identifying how big a role the Marian wind played in depositing concentrations of minerals often associated with water across the planet, as opposed to those minerals accumulating in those areas as a direct consequence of water once having been present.

Next NASA Rover to Have its Own Drone?

In January I wrote about ongoing work to develop a helicopter “drone” which could operate in concert with future robot missions to Mars. Now the outgoing director of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory has indicated the centre would like to see such a vehicle officially included as a part of the Mars 2020 rover package.

Weighing just one kilogramme (2.22 pounds) and with a rotor blade diameter of just over a metre (3.6 feet), the drone would be able to carry a small instrument payload roughly the size of a box of tissues, which would notably include an imaging system. Designed to operate as an advanced “scout”, the drone would make short daily “hops” ahead of, and around the “parent” rover to help identify safe routes through difficult terrain and gather data on possible points of scientific interest which might otherwise be missed and so on.

Since January, JPL has been continuing to refine and improve the concept, and retiring JPL Director Charles Elachi has confirmed that by March 2016, they will have a proof-of-concept design ready to undergo extensive testing in a Mars simulation chamber designed to reproduce the broad atmospheric environment in which such a craft will have to fly. The centre hopes that the trials will help convince NASA management – and Congress – that such a drone would be of significant benefit to the Mars 2020 mission, and pave the way for developing drones which might be used in support of future human missions on the surface of Mars.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: the sand dunes of Mars and flying to the ISS”