As generally happens in long-duration space missions, media attention around Curiosity is waning somewhat as the initial gee-whiz factor wears off and the reality of this potentially being a multi-year mission kicks-in and journos start seeking the next gee-whiz headline. As such, the next time Curiosity really hits the headlines, it’ll likely be for one of three reasons: Something Big has happened science-wise; someone has sensationalised upcoming news a-la Joe Palca; or something on the rover has broken. Indeed, a combination of the second two points is already occurring.

As generally happens in long-duration space missions, media attention around Curiosity is waning somewhat as the initial gee-whiz factor wears off and the reality of this potentially being a multi-year mission kicks-in and journos start seeking the next gee-whiz headline. As such, the next time Curiosity really hits the headlines, it’ll likely be for one of three reasons: Something Big has happened science-wise; someone has sensationalised upcoming news a-la Joe Palca; or something on the rover has broken. Indeed, a combination of the second two points is already occurring.

But that’s the nature of news cycles. Once the glamour and the wow has worn off, the interest fades and it is only the sensational (or titillating, in some circumstances) which does get reported. It’s why news and feature editors aren’t really interested in hearing about Second Life (“Second Life? You show me a million people a day are signing-up to it, and I’ll run it. Otherwise all you have is yesterday’s news…”).

In the meantime, Curiosity rolls onward towards “Mount Sharp” is what is still only the prelude to its mission on Mars; a prelude which has already yielded remarkable results in just four short months.

Choreographing a Self-portrait

Ever tried to take a picture of yourself? It’s not easy unless you have some frame of reference to guide you – such as an LED screen on your camera / device on which you can actually see how the shot will look prior to taking it. “Great photo, other than the fluffy bunny apparently trying to climb out of your right ear….”

Imagine how much harder it is to do the same remotely over a distance of more than 90 million kilometres (56 million miles). Yet on Sols 84 and 85 (October 31st / November 1st), that’s precisely what Curiosity did, producing a beautiful high-resolution composite image of itself quickly seen the world over.

The portrait was put together using dozens of high-resolution images captured using the rover’s Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI), located on the turret at the end of Curiosity’s robot arm in a complex series of manoeuvres. But this wasn’t just a case of point-and-click and hope for the best, then go back and try again. Everything had to be planned well in advance earth-side prior to the rover being told to “get on with it”.

But how do you choreograph something over a distance of 90 million kilometres? Phoning home in brief bursts isn’t going to cut it.

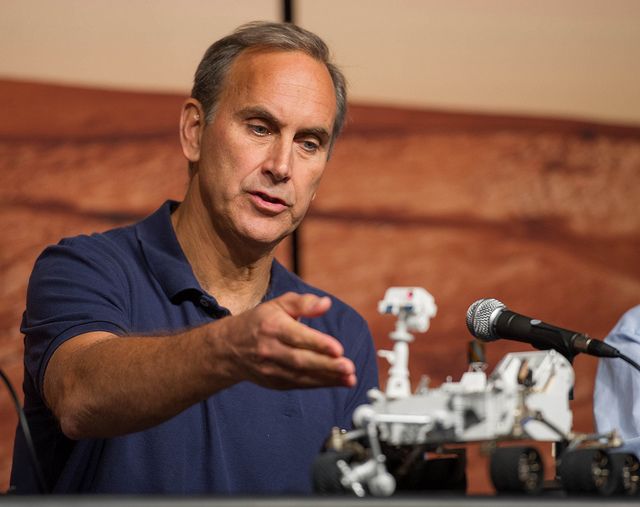

Enter Curiosity’s earth-based “twin”, another of the unsung heroes of the MSL mission. Located at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, the VSTB – Vehicle System Test Bed – is the closest thing NASA have to a “second Curiosity“. It comprises all of Curiosity’s major elements – wheels, chassis, bodywork, drive system, electrical system, mast, camera systems, robot arm, turret systems and so on (all minus the nuclear “battery” powering the real MSL rover) – and it forms a critical element of the overall mission. Using the VSTB engineers can troubleshoot any issues which may occur with the rover’s major systems and mission planners can map complex manoeuvres using things like the robot arm, allowing them to build up a precise set of commands required to perform a given task prior to uploading them to Curiosity on Mars and allowing the rover to carry them out.

Please use the page numbers below to continue reading this article