Curiosity, NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory rover has departed “Marias Pass”, a geological contact zone between different rock types on the slopes of “Mount Sharp”, some of which yielded unexpectedly high silica and hydrogen content.

Curiosity, NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory rover has departed “Marias Pass”, a geological contact zone between different rock types on the slopes of “Mount Sharp”, some of which yielded unexpectedly high silica and hydrogen content.

As noted in a recent space update in these pages, silica is primarily of interest to scientists, because high levels of it within rocks could indicate ideal conditions for preserving ancient organic material, if present. However, as also previously noted, it may also indicate that Mars may have had a continental crust similar to that found on Earth, potentially signifying the geological history of the two worlds was closer than previously understood. Hydrogen is of interest to scientists as it indicates water bound to minerals in the ground, further pointing to Gale Crater having once been flooded, and “Mount Sharp” itself the result of ancient water-borne sediments being laid down over repeated wet periods in the planet’s ancient past.

Curiosity actually departed “Marias Pass” on August 12th, after spending a number of weeks examining the area, including a successful drilling and sample-gathering operation at a rock dubbed “Buckskin”, where the rover also paused to take a “selfie”, which NASA released on August 19th. It is now continuing its steady climb up the slopes of “Mount Sharp.”

As it does so, initial analysis of the first of the samples gathered from “Buckskin” is under-way. It is hoped with will help explain why the “Marias Pass” area seems to have far higher deposits of hydrogen bound in its rocks than have previously been recorded during the rover’s travels. This data has been supplied by the Dynamic Albedo of Neutrons (DAN) instrument on Curiosity, which almost continuously scans the ground over which the rover is passing to gain a chemical signature of what lies beneath it.

“The ground about 1 metre beneath the rover in this area holds three or four times as much water as the ground anywhere else Curiosity has driven during its three years on Mars,” said DAN Principal Investigator Igor Mitrofanov of Space Research Institute, Moscow, when discussing the “Marias Pass” DAN findings. Quite why this should be isn’t fully understood – hence the interest in what the drill samples undergoing analysis might reveal.

The drilling operation itself marked the first time use of the system since a series of transient short circuits occurred in the hammer / vibration mechanism in February 2015. While no clear-cut cause for the shorts was identified, new fault protection routines were uploaded to the rover in the hope that should similar shorts occur in the future, they will not threaten any of Curiosity’s systems.

A Flight over Mars

With all the attention Curiosity gets, it is sometimes easy to forget there are other vehicles in operation on and around Mars which are also returning incredible images and amounts of data as well – and were doing so long before Curiosity arrived.

One of these is Europe’s Mars Express, the capabilities of which come close to matching those of NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Mars Express has been in operation around Mars for over a decade, and in that time has collected an incredible amount of data.

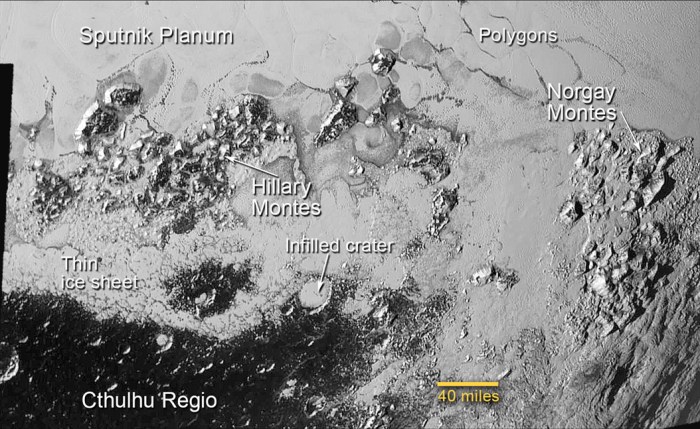

At the start of August, ESA released a video made of high resolution images captured by the orbiter of the Atlantis Choas region of Mars. This is an area about 170 kilometres long and 145 wide (roughly 106 x 91 miles) comprising multiple terrain types and impact craters, thought to be the eroded remnants of a once continuous ancient plateau. While the vertical elevations and depressions have been exaggerated (a process which helps scientists to better understand surface features when imaged at different angles from orbit), the video does much to reveal the “magnificent desolation” that is the beauty of Mars.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: of selfies, sprites, and black holes”