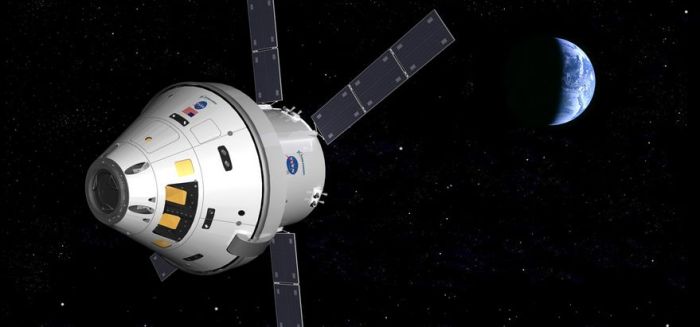

NASA has confirmed the first flight of the Orion / Space Launch System (SLS) will not include a crew. As I recently reported, the US space agency had been considering shifting gear with with the new combination of launch vehicle and the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle to include a crew on the maiden flight, referred to as Exploration Mission 1 (EM-1). The change in direction was prompted by a request from the Trump administration to acting NASA Administrator Richard Lightfoot, in an attempt to accelerate the human space flight programme.

On Friday, May 12th, Lightfoot indicated that while it would be technically feasible to make EM-1 a crewed mission, the agency would not do so on the grounds of costs. For an uncrewed flight, the Orion vehicle does not need to be equipped the life support, flight control and other additional systems a crew would need. would require. Doing so would require an additional expenditure of between US $600 and $900 million – costs which would otherwise be deferred across several years in the run-up to the originally planned crewed launch for Orion / SLS – called EM-2, slated for 2021. However, EM-1 will still be delayed until mid-2019.

The reasons for the EM-1 delay are due to unrelated issues with various parts of the Orion / SLS programme. Again, as covered in recent Space Sunday updates, the European-built Service Module, which will provide the Orion capsule with power, consumables and propulsion, is running behind schedule. In addition, the programme is also experiencing delays in developing key software.

These issues mean that pushing back the EM-1 launch was fairly inevitable. Had NASA been able to comfortably combine equipping the Orion vehicle for a crewed launch in 2019, then it would have roughly coincided with the 50th anniversary the first human lunar landing by NASA astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin during the Apollo 11 mission in July 1969. Instead, NASA will continue implementing the current baseline plan, with the second Orion / SLS flight carrying a crew into space. However, this mission may also be pushed back beyond 2021.

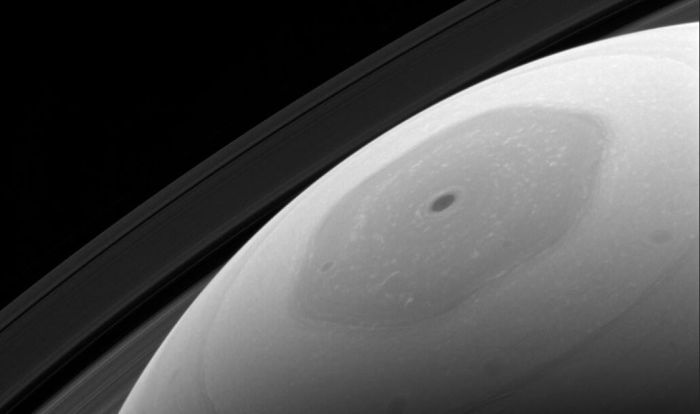

Saturn’s Hexagon to Star in Cassini’s Finale

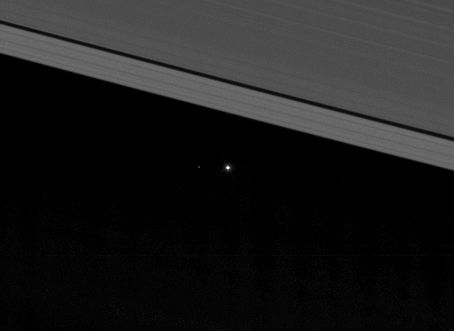

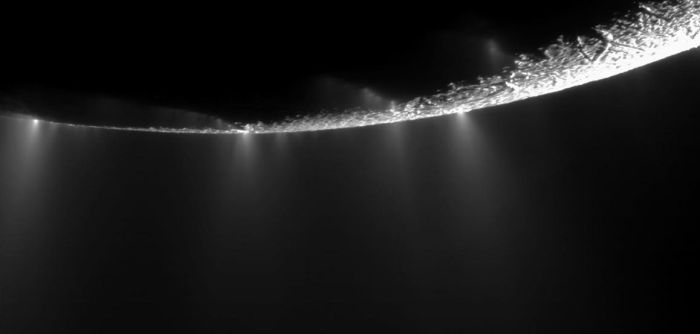

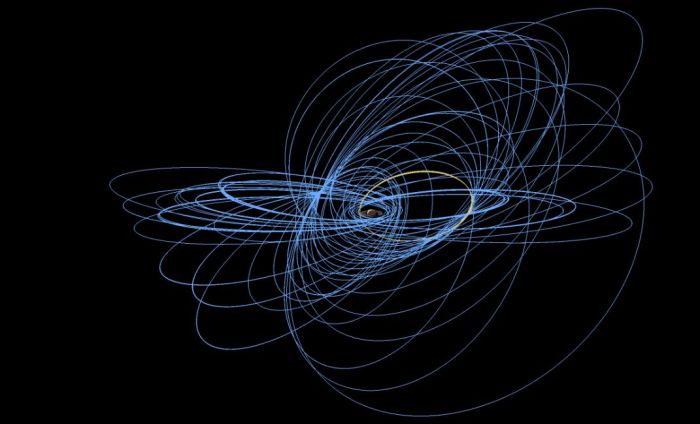

As I’ve been covering, the joint NASA-ESA Cassini mission to Saturn is now in its last phase, as the spacecraft makes a final series of 22 orbits around the planet, diving between Saturn’s cloud tops and its rings in the process.

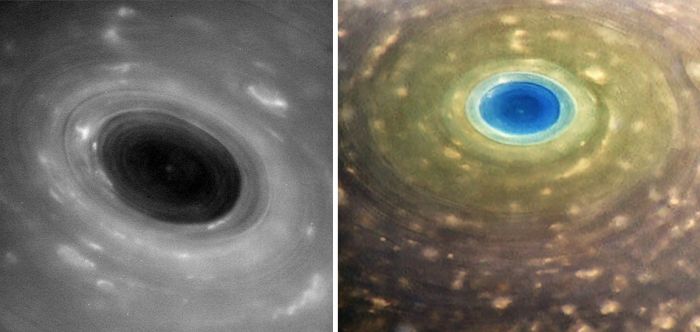

However, in addition to exploring a region of space no other mission has properly examined, Cassini’s final series of orbits around Saturn provide an unprecedented opportunity to study the massive hexagonal storm occupying the atmosphere of the planet’s northern polar region.

First seen by the Voyager missions which flew by Saturn in 1980 and 1981 respectively, the storm is of a massive size – each side of the hexagon measures around 13,800km (8,600 mi), greater than the diameter of Earth.; it rotates at what is thought to be the speed of the planet’s interior: once every 10 hours 39 minutes. However, due to Saturn’s distance from the Sun (an average of 9.5549 AU) and its axial tilt (26.73°), the northern polar region only gets about 1% as much sunlight as Earth does; making steady observations of the storm difficult. Cassini’s final series of orbits, passing as they do over Saturn’s north pole offers a unique opportunity to examine the storm in some detail.

During the first passage between Saturn and its rings on April 26th, Cassini captured a string of black-and-white images of the region, include the vortex at the centre of the storm, which were subsequently stitched together into a short movie (above).

The passes over Saturn during these final orbits should allow Cassini to use its wide-angle camera to gather detailed images of the storm whenever possible, which may in turn help scientists probe its secrets – including what is powering it, and why it has such a clearly defined boundary between itself and Saturn’s atmosphere at lower latitudes.

Cassini has already completed two “ring dives”, with the third scheduled pass occurring on Monday, May 15th. The mission as a whole will end on September 15th, when the vehicle will enter the upper reaches of Saturn’s atmosphere and burn-up.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: launches, storms, simulations, and space walks”