It’s been a further busy week for NASA’s InSight Lander as it starts to get down to business. In particular, the rover has been further exercising its robot arm and preparing for the start of operations – work that has involved surveying its local surroundings.

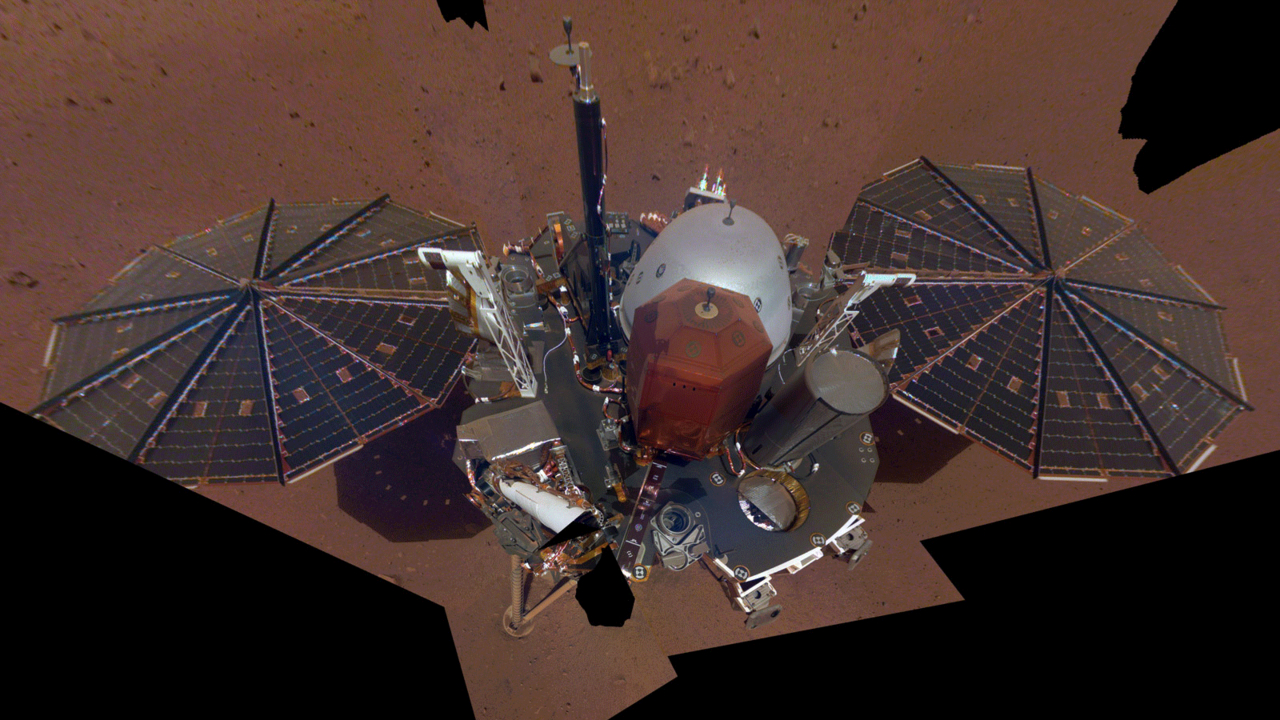

The week started with NASA releasing InSight’s first “selfie”, a mosaic of 11 images captured by the Instrument Deployment Camera (IDC), located on the elbow of the lander’s robotic arm. Clearly visible in the completed image is the copper-coloured seismometer that will be placed on the surface of Mars to listen to the planet’s interior with its silver protective dome just behind it. Also visible is the black boom of the robot arm rising mast-like.

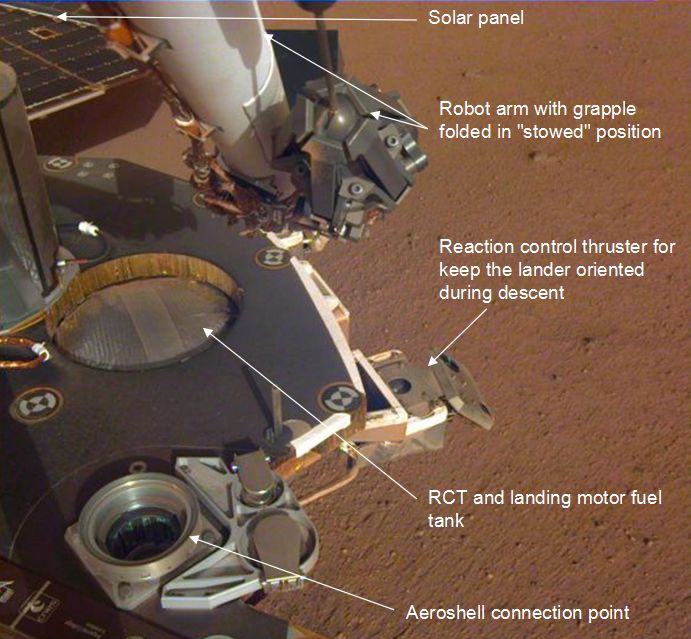

The IDC is one of two camera systems on InSight, but the only one that is fully mobile. It will be used in conjunction with the Instrument Context Camera (ICC), fixed to the lander’s hull, to correctly place the surface instruments of the SEIS seismometer and the HP3 drilling mechanism on Mars.

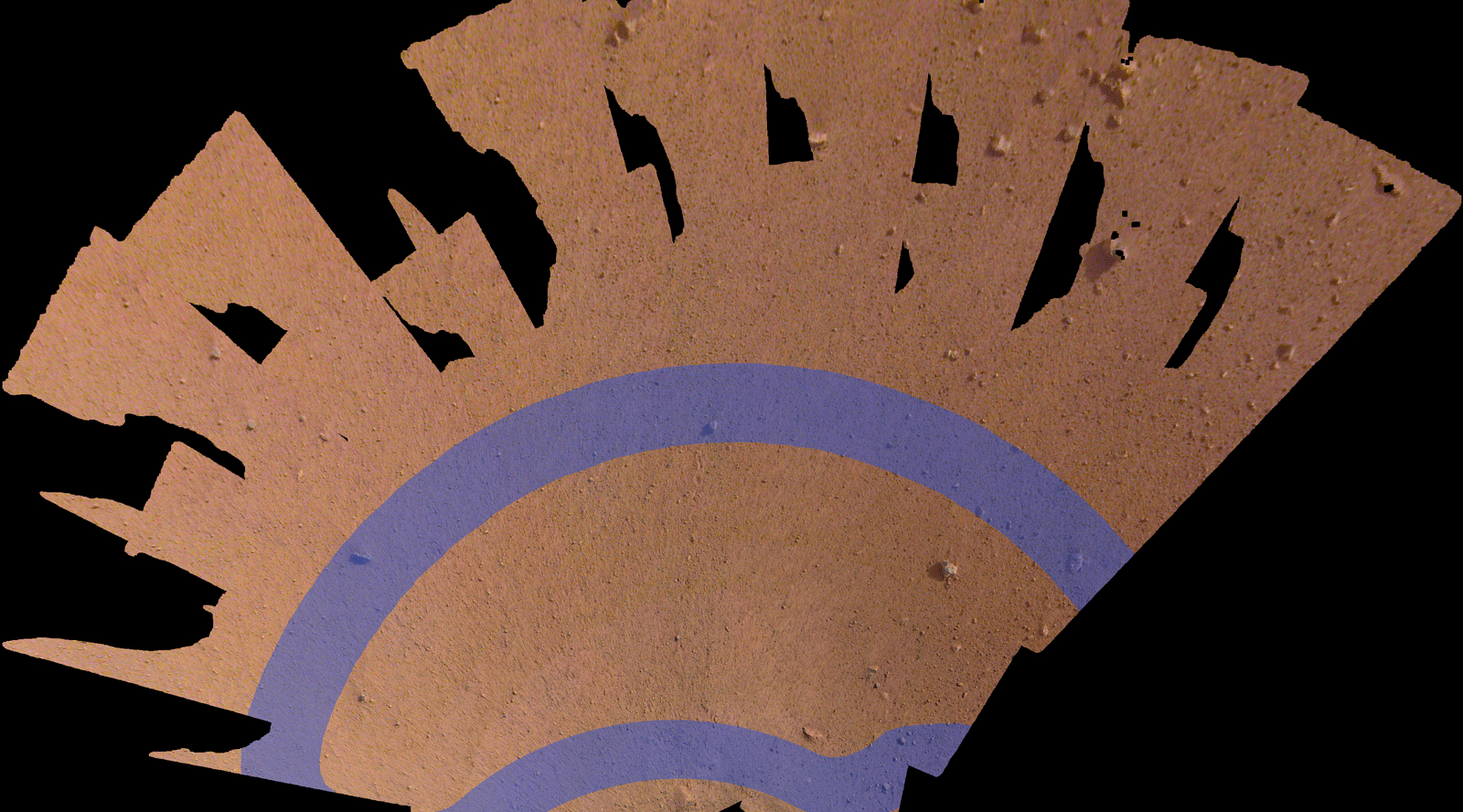

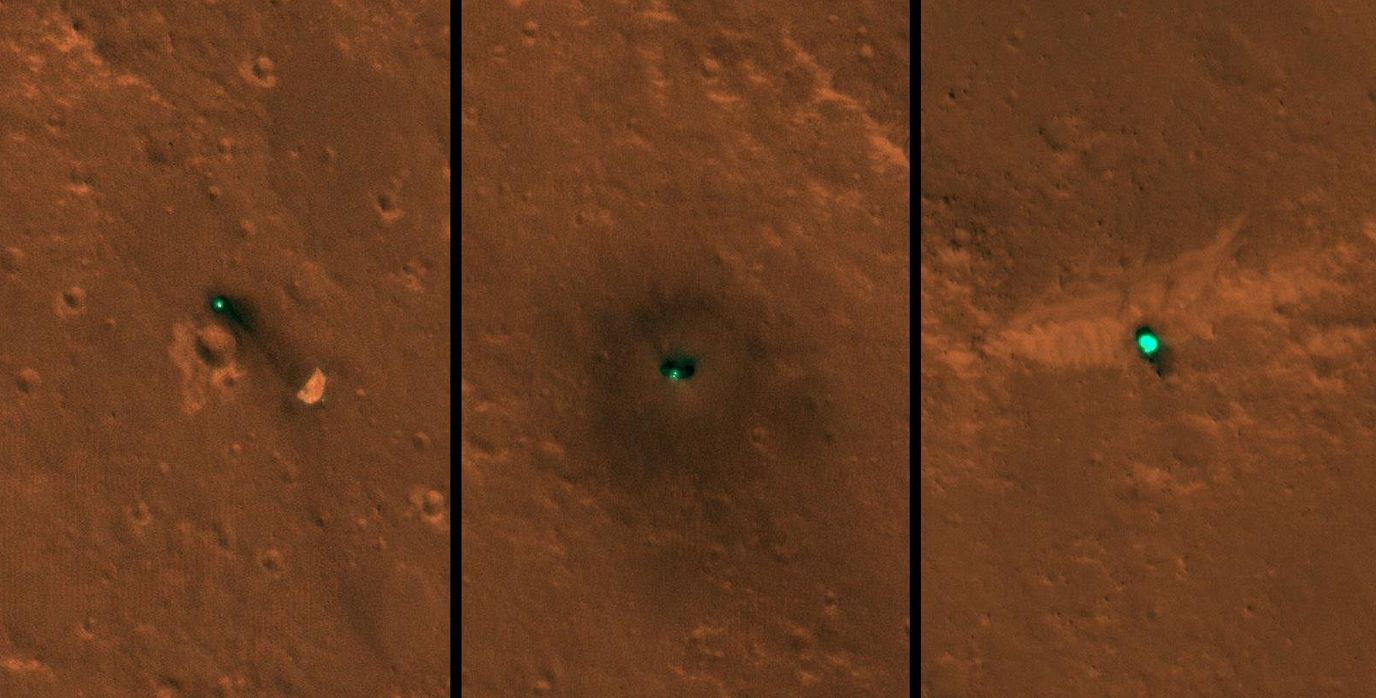

The static nature of the ICC means that placement of the surface instruments is limited to an arc directly in front of the lander, and as well as taking selfies, InSight has been using the IDC to survey this area from above.

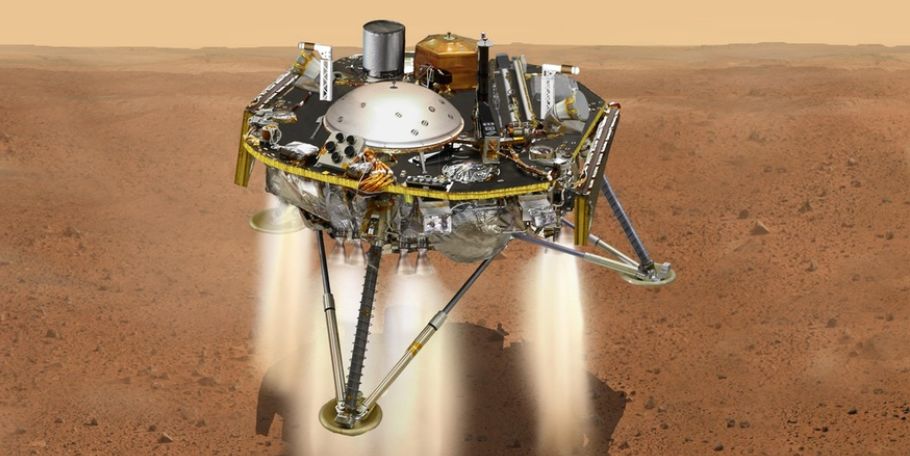

Deployment of these two instruments will take time. While operations will start in the coming week, they will likely take around two months to complete. The SEIS will be deployed first. This will be a complex task, placing the unit on the surface first, followed by its protective cover, designed to prevent the Martian wind and atmospheric changes affecting the readings the seismometer takes of the planet’s interior.

If all goes according to plan, the HP3 will be deployed in around mid-January. It will commence operations as soon as possible after deployment. However, it will be an extended process before the instrument starts to deliver on its science goals. This is because the self-hammering heat probe within HP3 – nicknamed the mole – has to “drill” its way some 5 metres (16ft) below the Martian surface. However, it will take time because the probe must pause periodically to release a burst of heat that will help it determine the nature of the material around it and possible hazards below it.

They were speaking about the seven minutes of terror on landing, now I’m saying we have two months of terror in front of us when we penetrate into the surface. The drilling mechanism relies on pushing aside dirt. Smaller rocks it can either push aside or burrow around, but a large rock – 1 metre [3ft] in diameter or so – would stymie the probe’s drilling mechanism.

– Tilman Spohn, of the German space agency DLR, and HP3’s principal investigator

In particular, the effectiveness of HP3 depends on how deeply it penetrates the regolith.

The less we penetrate, the worse it will be. If it’s just 1 m (3 ft) or so deep, the team will need to rely on more intensive modelling. But if it reaches 3 m (10 ft), which should occur around mid February, the team will be pleased — and if it can reach the full depth of 5 m (16 ft) around March 10th or so, all the better.

– Tilman Spohn

The survey of the landing site has helped confirmed that despite early misgivings when InSight first touched-down, the area occupied by the lander is about as free from rocks and possible surface hazards for SEIS and HP3 as might have been possible to find.

Virgin Galactic Reaches Space with VSS Unity

On December 13th, 2018, Virgin Galactic carried out a supersonic flight test that carried VSS Unity into space for the first time – at least according the NASA’s and the US Air Force’s reckoning. The success of the flight takes Virgin Galactic closer to taking paying customers on the six-passenger rocketplane, which is about the size of an executive jet, on sub-orbital flights into space.

Unity, also referred to as SpaceShipTwo, was carried aloft by its mothership, WhiteKnightTwo from the Mojave Space Port to an altitude of 13,100 metres (43,000 feet). It was then dropped from the carrier jet, allowing the crew of two, Mark “Forger” Stucky and former NASA astronaut Rick “CJ” Sturckow, to ignite the single rocket motor. Burning for 60 seconds, the motor allowed Unity to start a rapid climb and achieved Mach 2.9, nearly three times the speed of sound.

After engine cut-out, the vehicle continued to climb for a further minute, reaching an altitude of 82 km (51 miles) – enough to put it across the line NASA and the US air Force consider to be the edge of space relative to Earth (80 km / 50 mi above sea level).

Once Unity reached apogee, the two pilots were afforded some brief moments of microgravity. They then “feathered” the tail booms, causing the vehicle to gently fall back into the denser atmosphere like a shuttlecock. Once air density was sufficient, the tail sections returned to their “regular” position, allowing the vehicle to achieve unpowered aerodynamic flight, landing back at Mojave Air and Space Port at 08:14 local time (16.14 UTC), with the flight from the drop to the landing lasting 14 minutes in total.

While NASA and the US Air Force view the edge of space being at 80 km, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI), the international standard-setting and record-keeping body for aeronautics and astronautics, officially place the boundary between atmosphere and space – called the Kármán line – at 100 km (62 mi; 330,000 ft). Nevertheless, the flight is enough for Stucky to gain his astronaut wings, and for Virgin Galactic to talk in terms of commencing passenger-carrying operations in the near future.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: InSight, space and interstellar space”