A Soviet-era space mission finally drew to a close on Saturday, May 10th, 2025 (UTC) after 53 years in space – although admittedly, that wasn’t really the plan when it was launched. Also, it’s fair to say that for the vast majority of that time, it has been little more than a hefty lump of space junk looping repeatedly around the Earth rather than doing anything useful.

However, its return marks an opportunity to recall an interesting period of the early era of the space age. A time when both the US and the Soviet Union were just starting to get to grips with lobbing humans into orbit, but when the latter already had grander designs in mind – starting with an aggressive programme to study Venus.

Initiated in 1961 – the same year as a human first flew into space – the Soviet Venus, or Venera, programme was a daring and high-stakes programme given the overall reliability and sophistication of rocket vehicles and space probes at the time. Thus, over a period of 23 years and 29 missions, it had a fair few highs and lows.

For example, of those 29 missions, 12 never even made it Venus, while several others didn’t go fully to plan. However, of those that did get to Venus, their successes were remarkable, whether or not all mission objectives were achieved:

- The first fly-by of another planet (Venera 2, 1965/66- although contact was lost prior to any data being returned).

- The first vehicle to impact the surface of Venus (Venera 3, 1965/66 and twin to Venera 2, although a failure with the carrier vehicle meant that again, no data was returned).

- The first vehicle to reach the atmosphere of another planet and return data to Earth (Venera 4, 1967).

- The first vehicles to perform a deep analysis of the atmosphere of Venus, down to an altitude of around 20 km (Venera 5 and Venera 6, 1969).

- The first vehicle to successfully land on another planet and return data from it (Venera 7, 1970).

- The first vehicles to successfully return images from the surface of Venus (Venera 9 and Venera 10, 1975).

- The first vehicles to return colour images from the surface of Venus and the first to record sounds from Venus -the wind the mechanical operations associated with the landers. (Venera 13 and Venera 14, 1982).

- The first vehicles to deploy balloons on Venus (Vega 1 and Vega 2, 1985).

Among these missions, some are worth a little further highlighting. For example, because it was still considered that the surface of Venus could have liquid water present, Venera 4 was designed to float in event of a splashdown, despite massing 383 kg. It was also fitted with antenna deployment locks made of sugar.

The idea behind this latter point was that if Venera 4 landed on water, the impact force might not be sufficient to trigger the release of the locking mechanism and allow the main communications antenna deploy. However, the impact on water would result in the locking mechanism being splashed with water – which would (in theory) dissolve the mechanism, allowing the antenna to be deployed!

It was initially thought that Venera 4 was the first vehicle to actually reach the surface of Venus. However, due to a combination of error margins built into some of the instruments coupled with inconsistencies between data obtained by Venera 4 and later probes, it is now believed that Venera 4 only reached somewhere between 55 and 26 km above the planet’s surface before succumbing to the harsh conditions.

Whilst Venera 5 and Venera 6 also failed to reach the surface of Venus in an operational capacity, they are remarkable as they were able to remain aloft for more than 50 minutes each, drifting under their parachutes and gathering data on the nature and composition of the planet’s atmosphere, gently descending to with 20 km of the surface before finally being overwhelmed.

The story of Venera 7 is in part one of diligence over dismissal. Immediately after receiving confirmation the vehicle was on the surface of Venus, mission controller seemed to lose all contact with the lander. Attempts were made to re-establish contact, with the recording tapes on the communications link still recording. Eventually, unable to diagnose the issue, the mission was dismissed as lost without data.

However, several weeks later, radio astronomer Oleg Rzhiga decided to review the recordings of the landing and subsequent events. In doing so, he found 23 minutes of faint, data-carrying signal had in fact received from the lander. Venera 7 hadn’t failed, it had simply been knocked off-axis on landing, resulting in its radio signal only being faintly received but passed unnoticed by mission controllers at the time.

Finally, there are the two Vega missions, remarkable for a number of reasons. “VeGa” is actually a westernisation of ВеГа, itself taken from the first two letters of the Russian for “Venus” (Венера) and Галлея (“Halley” – or “Galleya”). This latter part of the name indicated their primary mission focus – rendezvousing with Comet Halley, which was making one of its (on average) 76-year revisits to the inner solar system.

However, in order to reach the comet, the probes would need a gravity assist from Venus. This meant that they could also piggyback Venus-centric missions, releasing them as they approached Venus for their fly-by. The Venus element comprised two landers of a similar design to earlier Venera craft, and intended to study both the atmosphere and surface of the planet. Unfortunately, turbulence encountered during descent caused the surface instruments on the Vega 1 lander to activate before touch-down, so that only the mass spectrometer returned data once on the surface. The Vega 2 lander was more successful, returning data for a period of 56 minutes, post-landing.

The more fascinating part of these missions was the use of balloons. These were released as a package by the landers at some 60 km above the surface of Venus. Parachutes initially slowed their descent to a point where, at an altitude of around 50 km, a mechanism attached to the parachute systems inflated each balloon with helium, the parachute and inflation system then being jettisoned. This allowed both balloons, each dangling a 7 kg gondola of instruments, to climb back to an altitude of some 53 km, which they drifted 11,000 km around Venus – 30%of its circumference – transmitting data to their respective Vega craft for relay to Earth. Both balloons were still actively transmitting when the Vega craft passed out of communications range, 45 minutes after the balloons started sending data.

Of the failures, the majority came, not unreasonably, in the early days of the programme. Of the first eight attempts to reach Venus between February 1961 and April 1964 (launch dates), all failed. As a result, six were never officially designated – as was the Soviet approach in the first years of their space programme (i.e. if it doesn’t have an official designation, it didn’t happen and so couldn’t have failed). Of the remaining two, one gained the Venera 1 designation, as it made it out of Earth orbit (but failed while en route to Venus) and the other being designated a “Kosmos” mission.

Originally, “Kosmos” was a catch-all designation for Soviet Earth-orbiting uncrewed missions. It was intended to obfuscate and confuse western agencies, in that it didn’t matter the object in question was a piece of test hardware or a surveillance satellite or a communications relay, or a navigation beacon, or a weather satellite or whatever. If it was orbiting the Earth, it was called “Kosmos” and given a number. In 1962, the designation was extended to include any Soviet interplanetary probe that failed to leave Earth orbit, allowing failure to be hidden in plain sight. Only after a mission was on its way to its intended destination would it be given an actual mission designation (e.g. Venera 1, etc.).

Within the Soviet-era Venera programme, five vehicles gained the Kosmos designation:

- Kosmos 27 (one of two Zond missions for Venus launched on March 27th, 1964, and breaking-up in the upper atmosphere 24 hours later after failing to achieve a stable orbit).

- Kosmos 96 (launched on 23rd November 1965, failed to depart Earth orbit, burned-up in the upper atmosphere on December 9th, 1965, possibly resulting in the Kecksburg UFO incident).

- Kosmos 359 (launched on 22nd August, 1970, suffered an upper stage motor failure and re-entered the atmosphere on November 6th, 1970)

- Kosmos 482 – the cause of this article, and of which more below.

Intended to be the partner probe to Venera 8 (keeping to the naming convention to the actual run of successes), what was to become Kosmos 482 was launched on March 31st, 1972. However, a malfunction occurred as the upper stage booster motor was re-lit to transfer the probe onto its trajectory to rendezvous with Venus, and the vehicle broke up.

Some of the debris from the break-up fell to Earth in the form of 38-cm diameter, 13.6 kg titanium pressure spheres, most likely from the booster stage. These struck crop fields just outside of Ashburton, New Zealand, 48 hours after launch. However, the two larger elements of the break-up were pushed into 210 km x 9,800 km elliptical orbit around Earth, initially travelling close together, gaining the Kosmos 482 designation.

In the west, there larger of these two elements was identified as the remnants of the booster rocket and the Venus Bus, intended to provide power to the 495 kg lander. They were given the Designation 1972-023A. The smaller of the two was identified as most likely being the lander itself, clearly separated from its bus and booster, and so designated 1972-023E.

Over the next nine years, the two travelled in partnership, looping around the Earth, each pass having an increasing effect of 1972-023A, which gradually started breaking up, depositing pieces of itself to burn-up in the atmosphere (some surviving to fall on poor New Zealand again!) until it succumbed to atmosphere friction and burned-up on re-entry in mid-1981.

The lander – or 1972-023E – was made of sterner stuff, and continued to loop around Earth largely unfazed and forgotten. But each time it did make a close flyby there was exchange: a little velocity here, a little change in trajectory there. Over the decades, these little changes served to pull the craft closer and closer to Earth, such that by this year, it was looping around us once every 80-90 minutes, with its apogee and perigee both slipping into sub-200 km altitude figures. All of which meant that atmospheric entry was all but certain; the question was when? By the start of May 2025, NASA and ESA were looking to a re-entry window extending from May 9th through May 13th,which was then quickly narrowed down to the early hours of May 10th (UTC) – albeit with an initially wide margin of error (+/- 3.3 hours).

Given the orbital track of the debris, and the fact it was designed to survive the much tougher entry into the atmosphere of Venus, there were fears it could come down intact on a populated area. However, this was always unlikely, given that while it did pass over population centres each and every orbit, it also passed over large tracts of largely empty land (in human habitation terms), and even greater amounts of open ocean. Further, even if it did survive re-entry (not an absolute certainty given that both its age and the fact it would likely start tumbling during an uncontrolled atmospheric and most likely break-up / burn-up), it would not come crashing through the atmosphere at a huge velocity and explode in a massive air-burs. Rather, it would fall with a maximum velocity of around 250 km/h – enough to be decidedly upsetting if it hit a building or similar, but not enough to result in something like a city-wide disaster.

As it is, and at the time of writing, Roscosmos have stated that the vehicle re-entered the atmosphere at 06:24 UTC on May 10th over the Bay of Bengal, 560 km west of the Andaman Islands and prior to impacting the Indian Ocean somewhere west of Jakarta, Indonesia. However, this had yet to be confirmed by other agencies, although ESA indicated the vehicle potentially re-entered the atmosphere between 06:04 and 07:32 UTC, which would place its impact point most likely somewhere in the Indian or Pacific Oceans.

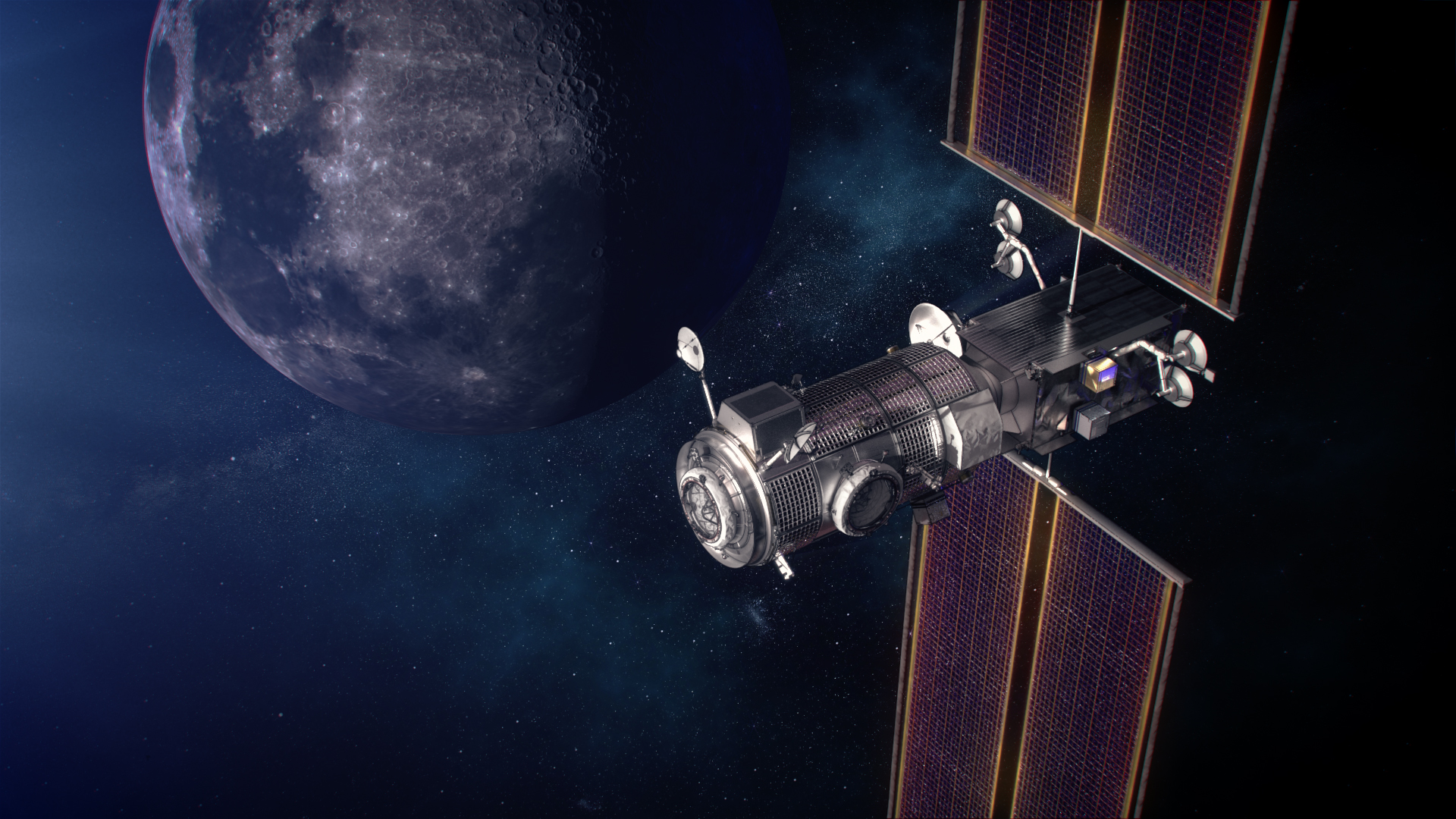

Kosmos 482 marked the last failure within the Soviet-era Venera programme, and its return to Earth acts as a very physical closure to that era of space history. However, it does not close the book on Russia’s ambitions where Venus is concerned. Currently, Russia is planning a return to Venus as it resumes its Venera programme with Venera D.

This mission – which is subject to a lot of ifs and maybes, already having been delayed on multiple occasions. When first conceived in 2003, it was targeting a 2013 lunch date; currently, the mission is slated for a launch no earlier than 2031, although it has yet to have its science packages finalised and developed. Comprising an orbiter and lander, if it does go ahead, Venera D (also sometimes called Venera 17) will deliver heavyweight (1.6 tonne) lander to the surface of Venus with the intentions of it being able to survive and carry out science studies for up to 3 hours after landing.