The United States has now formally announced its intention to end the International Space Station that the start of 2031.

The announcement comes on top of confirmation that the Biden-Harris administration has confirmed ISS operations should continue through until the latter half of 2030. In it, the agency confirms that they plan to replace the ISS with at least three commercial space stations under a joint public-private arrangement that will see the new facilities in part built using taxpayer’s funding through NASA, allowing them to be used for both NASA-operated and private sector research and other activities.

These new space stations will be developed during the nine years of remaining life for the ISS, allowing operations to gradually pivoted to them as they are commissioned.

The private sector is technically and financially capable of developing and operating commercial low-Earth orbit destinations, with NASA’s assistance. We look forward to sharing our lessons learned and operations experience with the private sector to help them develop safe, reliable, and cost-effective destinations in space. The report we have delivered to Congress describes, in detail, our comprehensive plan for ensuring a smooth transition to commercial destinations after retirement of the International Space Station in 2030.

– Phil McAlister, director of commercial space, NASA

Within the plan, NASA also outline how the ISS is to be through to its end-of-life, and provides a brief summary of some of its achievements, including:

- Hosting more than 3,000 research investigations from over 4,200 researchers across the world.

- Allowing 110 countries and to participate in research activities performed aboard the

- Operating international STEM (Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) programme that has reached 1.5 million students world-wide each year it has been running.

- Allowed for major breakthroughs in a range of Earth and space sciences.

The International Space Station is entering its third and most productive decade as a ground-breaking scientific platform in microgravity. This third decade is one of results, building on our successful global partnership to verify exploration and human research technologies to support deep space exploration continue to return medical and environmental benefits to humanity, and lay the groundwork for a commercial future in low-Earth orbit.

– Robyn Gatens, director of the International Space Station, NASA

However, there are still bumps in the road in terms of NASA’s planning. Whilst the Biden-Harris administration has green lit the station through until the end of 2030, it is Congress that will largely have the final say in things from the US side – and Congress has mixed views on ISS, a 4-year extension of ISS operations from 2024-2028 having previously proven contentious. Such is the reality of things, there are doubts if some of NASA’s plan can be achieved – something I’ll get to in a moment – which may leave Congress again arguing over the future of the ISS.

Another possible sticking point is continued Russian involvement in the ISS. In 2021, the Russian government and their national space agency, Roscosmos, announced plans to launch their own, independent space station. Currently referred to as the Russian Orbital Service Station (ROSS), which they planned to have “fully operational” and comprising multiple modules by 2030.

These plans will see Russia launch two modules originally intended for the ISS and called SPM-1/NEM-1 and SPM-2/NEM-2 as the backbone for ROSS. The first of these modules is to be launched in 2024 and the second in 2028. However, under their original plans, Russia indicated that one SPM-1 was in orbit, they might actually detach the self-propelled Nauka science module together with the Prichal docking module attached to it (both delivered to the ISS in 2021) and move them to dock with the nascent ROSS facility, disrupting ISS operations.

But since then, the timeline for ROSS has been pushed out so that 2035 is now the target for completing 2035, potentially negating any need to remove modules from ISS in the late 2020s. Even so, that Russia is to push ahead with ROSS does level some concerns over their willingness to financially support ISS operations beyond 2028.

In terms of private venture facilities to replace the ISS, NASA initially indicated that 11 companies and organisations filed proposals under the agency’s Commercial Low Earth Orbit Destinations (CLD) programme. Several of these were rejected for a range of technical and practical issues, whilst three were granted initial seed funding amounting to US $415.6 million.

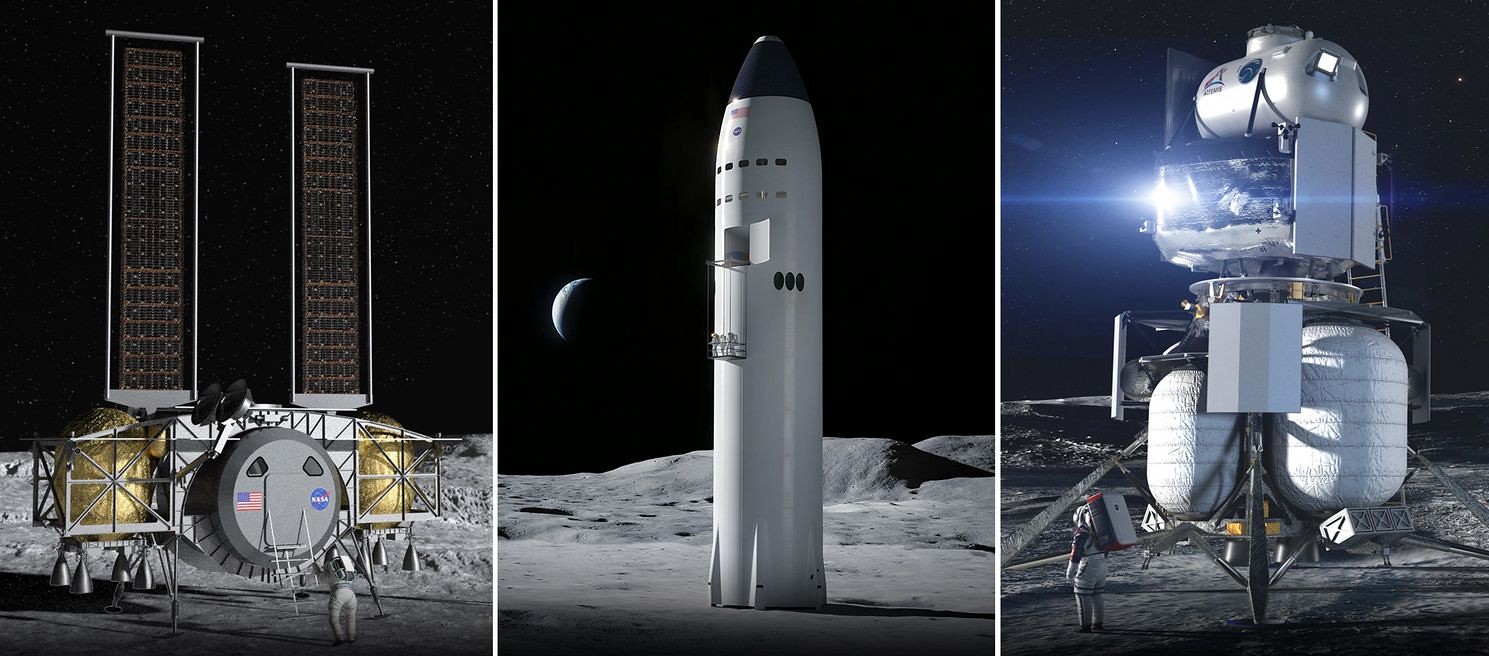

As I reported in December 2021, these three proposals are from Blue Origin / Sierra Space, Nanoracks and Northrop Grumman. Two further proposals received notes of merit by did not gain initial funding. One of these came from – unsurprisingly – SpaceX, who proposed using a variant of their Artemis lunar landing Starship vehicle, but failed to address core requirements – such as environmental support for long-duration missions, support for multiple vehicle docking and external payload handling capabilities.

The second proposal to receive merit came from an unexpected source: Relativity Space. This is 7-year-old start-up I’ve previously mentioned in these pages that is developing a line of expendable and reusable 3D-printed launch vehicles. They proposed perhaps the most novel concept to NASA: a small-scale research laboratory based on their yet-to-fly Terran-R reusable launch vehicle that could be placed in orbit and periodically returned to Earth for refurbishment, upgrade and re-launch.

At the time the initial CLD contracts were awarded, NASA’s own Office of Inspector General (OIG) was already casting doubt on whether the time frames for a private sector space station could be achieved:

In our judgment, even if early design maturation is achieved in 2025 — a challenging prospect in itself — a commercial platform is not likely to be ready until well after 2030. We found that commercial partners agree that NASA’s current timeframe to design and build a human-rated destination platform is unrealistic.

– NASA OIG report on commercial space stations, December 2021

Ergo, settling on December 2030 as an end date for ISS operations could again split Congress. On the one side, there might be those who believe the station should be financed beyond 2030 “just in case” alternatives are not available. On the other, the fact that alternatives may not be ready, coupled with recent concerns about issues with the ISS as a result of the increasing age of, and wear-and-tear to, the older modules on the station, might lead to calls for an earlier ISS “retirement” to allow funds to be targeted elsewhere.

But there is a potential alternative to a reliance on one of the CLD stations being rapidly developed. . Axiom Space already has a contract with NASA to launch a new module to the ISS in 2024 on a fixed-price basis. The module would be used for a mix of research and space tourism (Axiom will launch its first private crew to the ISS in March of this year aboard their Ax-1 mission). However, the company has additionally committed itself to developing four further modules, two of which they hope to add to the unit attached to the ISS by 2028 to form an “orbital segment”.

These three modules could then be detached from the ISS in 2030 to form a core of a new space station, to which the remaining to modules would be attached in the early 2030s. If Axiom can carry these plans forward between 2024 and 2030, then they could provide the means for NASA to pivot a fair portion of their ISS activities to the Axiom station and also to the CLD stations as they also come on-line in the 2030s, leaving the way clear for ISS to be decommissioned and de-orbited as announced.

This will actually start in around 2025, while the ISS is still in operation, when a gentle series of manoeuvres will be used to gradually lower the station’s altitude through until 2030. Then, after the last crew has departed the station, NASA intend to use the thrusters from a mix of Progress and Cygnus resupply vehicles to remotely lower the station and orient it so that as the frictional heat increases the larger, more delicate parts of the structure will burn up. The track of entry into the atmosphere will be designed so that what survives re-entry – liable to be a series of large sections falling in close proximity to one another – will fall into the southern Pacific Ocean in a region called Point Nemo between New Zealand and Chile, and 2,672 km from the nearest land, the traditional “graveyard” for objects making controlled returns from low Earth Orbit.