NASA’s ISS Expedition 73/74 crew, flying as SpaceX Crew 11, have made a safe and successful return to Earth following their medical evacuation from the space station.

As I reported in my previous Space Sunday piece, the decision to evacuate the entire 4-person crew, comprising NASA astronauts Zena Maria Cardman and Edward Michael “Mike” Fincke, together with Kimiya Yui of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Platonov, was made after one of the four suffered an unspecified medical issue. Details as to who has experienced the issue and what form it takes still have not been revealed – although when initially discussing bringing the crew back to Earth roughly a month ahead of their planned end-of-mission return, the agency did make it clear the matter was not the result of an injury.

NASA also made clear the move to bring the crew home was in no way an emergency evacuation – had it been so, there were options available to return the crew a lot sooner. Instead, the evacuation was planned so that the affected crew member could have their situation properly diagnosed on Earth, whilst allowing time for the combined crew on the ISS to wrap-up as much as possible with outstanding work related to their joint time on the station and to allow Fincke, as the current station commander, to hand-over to cosmonauts Sergey Kud-Sverchkov, who together with Sergey Mikayev and US astronaut Christopher Williams will continue aboard the station, where they will at some point in the next month be joined by the Crew 12 team from NASA.

The crew began prepping for their departure in the evening (UTC) of Wednesday, January 14th, when after a round of goodbyes to the three remaining on the ISS and then changing into the SpaceX pressure suits, the four Crew 11 personnel boarded Crew Dragon Endeavour, prior to the hatches between the spacecraft and station being closed-out and final checks run on the vehicle’s status in readiness for departure.

Following this, all four of the crew ran through a series of leak checks on their suits to ensure all connections with the Dragon’s life support systems were working, and Cardman – acting as the Crew 11 Mission commander and the experienced Fincke as the Crew 11 vehicle pilot – completed all pre-flight and power checks.

Undocking occurred at 22:20 UTC, slightly later than planned, Fincke guiding the spacecraft smoothly and safely away from the station until Endeavour moved through the nominal 400-metre diameter and carefully monitored “keep out sphere” surrounding the ISS. This “sphere” represents the closest any vehicle can come to the ISS whilst operating entirely independently from the station – vehicles can only move closer whilst engaged in actual docking manoeuvres.

Crossing the sphere’s outer boundary some 20 minutes later, Endeavour entered the “approach / departure ellipsoid” – a zone extending away from the ISS denoting, as the name suggests, the area of space along which vehicles can approach / depart the station and make a safe manoeuvres away should anything happen during an initial docking approach.

By 22:52 UCT, some 30 minutes after initial undocking, Endeavour transitioned away from the ISS and into its own orbit around the Earth, intended to carry to a position where it could commence it re-entry manoeuvres and make a targeted splashdown off the coast of California. The main 13.5-minute de-orbit burn was initiated at 07:53 UTC on January 15th, as Endeavour passed over the Indian Ocean and Indonesia. From here, it passed over the Pacific reaching re-entry interface with the denser atmosphere at 08:31 UTC. At this point communications were lost – as expected – for around 7 minutes as the vehicle lay surrounded by super-heated plasma generated by the friction of its passage against the denser atmosphere, prior to being re-gained at 08:37 UTC.

Splashdown came at 08:40 UTC, closing-out a 167-day flight for the four crew. Recovery operations then commenced as a SpaceX team arrived at the capsule via launches and set about preparing it to be lifted aboard the recovery ship, which also slowly approached the capsule stern-first. By 09:14 UTC, Endeavour had been hoisted out of the Pacific and onto a special cradle on the stern of the MV Shannon, allowing personnel on the ship to commence the work in fully safing the capsule and getting the hatch open to allow the crew to egress.

On opening the hatch, a photograph of the four crew was taken, revealing them all to be in a happy mood, the smiles and laughter continuing as they were each helped out of Endeavour with none of them giving any clues as to who might have suffered the medical condition. Gurneys were used to transfer all four to the medical facilities on the Shannon, but this should not be taken to signify anything: crews returning from nigh-on 6-months in space are generally treated with caution until their autonomous systems – such as sense of balance – etc, adjust back to working in a gravity environment.

Following their initial check-out, all four members of Crew 11 were flown from the Shannon to shore-based medical facilities for further examinations. The ship, meanwhile, headed back to the port of Long Beach with Endeavour. Following their initial check-outs in California, the four crew were then flown to Johnson Space Centre, Texas on Friday, January 16th for further checks and re-acclimatisation to living in a gravity environment. No further information on the cause of the evacuation or who had been affected by the medical concern had, at the time of writing, been given – and NASA has suggested no details will be given, per a statment issued following the crew’s arrival at Johnson Space Centre.

The four crew members of NASA’s / SpaceX Crew-11 mission have arrived at the agency’s Johnson Space Centre in Houston, where they will continue standard postflight reconditioning and evaluations. All crew members remain stable. To protect the crew’s medical privacy, no specific details regarding the condition or individual will be shared.

– NASA statement following the arrival of the Crew 11 members at JSC, Texas.

Artemis 2 on the Pad

The massive stack of the second flight-ready Space Launch System (SLS) rocket and its Orion MPCV payload, destined to carry four astronauts to cislunar space and back to Earth, rolled out of the Vehicle Assembly Building (VAB) at NASA’s Kennedy Space Centre atop its mobile launch platform, to make its way gently to Launch Complex 39B (LC-39B).

The rocket – comparable in size to the legendary Saturn V – and its launch platform slowly inched out of High Bay 3 at the VAB at 12:07 UTC, carried by one of NASA’s venerable Crawler Transporters at the start of the 6.4 kilometre journey.

The drive to the launch pad took almost 12 hours to complete, the average speed less than 1.6 km/h throughout. Standing 98 metres in height, SLS is powered by a combination of 4 RS-25 motors originally developed for the space shuttle, together with two solid rocket boosters (SRBs) based on those also used for the shuttle – although these boosters, with their tremendous thrust, will only be available to the rocket during the first couple of minutes of its ascent to orbit, helping to push it through the denser atmosphere before being jettisoned, their fuel expended.

The next major milestone for the launch vehicle is a full wet dress rehearsal on February 2nd, 2026. This involves a full countdown and fuelling of the rocket’s two main stages with 987 tonnes of liquid propellants, with the rehearsal terminating just before engine ignition. The wet dress rehearsal is a final opportunity to ensure all systems and launch / flight personnel handling the launch are ready to go.

It was the wet dress rehearsal that caused numerous problems for NASA with Artemis 1, the uncrewed flight of an Orion vehicle around the Moon in 2022, with repeated leaks occurring in the cryogenic propellant feed connections on the launch platform. These issues, together with a range of other niggles and the arrival of rather inclement weather, forced Artemis 1 to have to return to the VAB three times before it was finally able to launch.

Since then, changes have been made in several key areas – including the propellant feed mechanisms. The hope is therefore that the wet dress rehearsal for Artemis 2 will proceed smoothly as the final pre-flight test, and the green light will be given for a crewed launch attempt, possibly just days after the rehearsal. However, Artemis 2 will not be standing idle on the pad until February 2nd; between now and then there will be a whole series of tests and reviews, all intended to confirm the vehicle’s readiness for flight and ground controllers readiness to manage it.

Assuming everything does go smoothly, NASA is currently looking at Friday, February 6th, 2026 as the earliest date on which Artemis 2 could launch, with pretty much daily windows thereafter available through until February 11th, with further windows available in March and April.

As I’ve recently written, Artemis 2 will be an extended flight out to cislunar space over a period of 10 days, during which the 4-person crew of NASA astronauts Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover and Christina Koch and Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen will thoroughly check-out the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle and its fitness as a lunar crew transport vehicle.

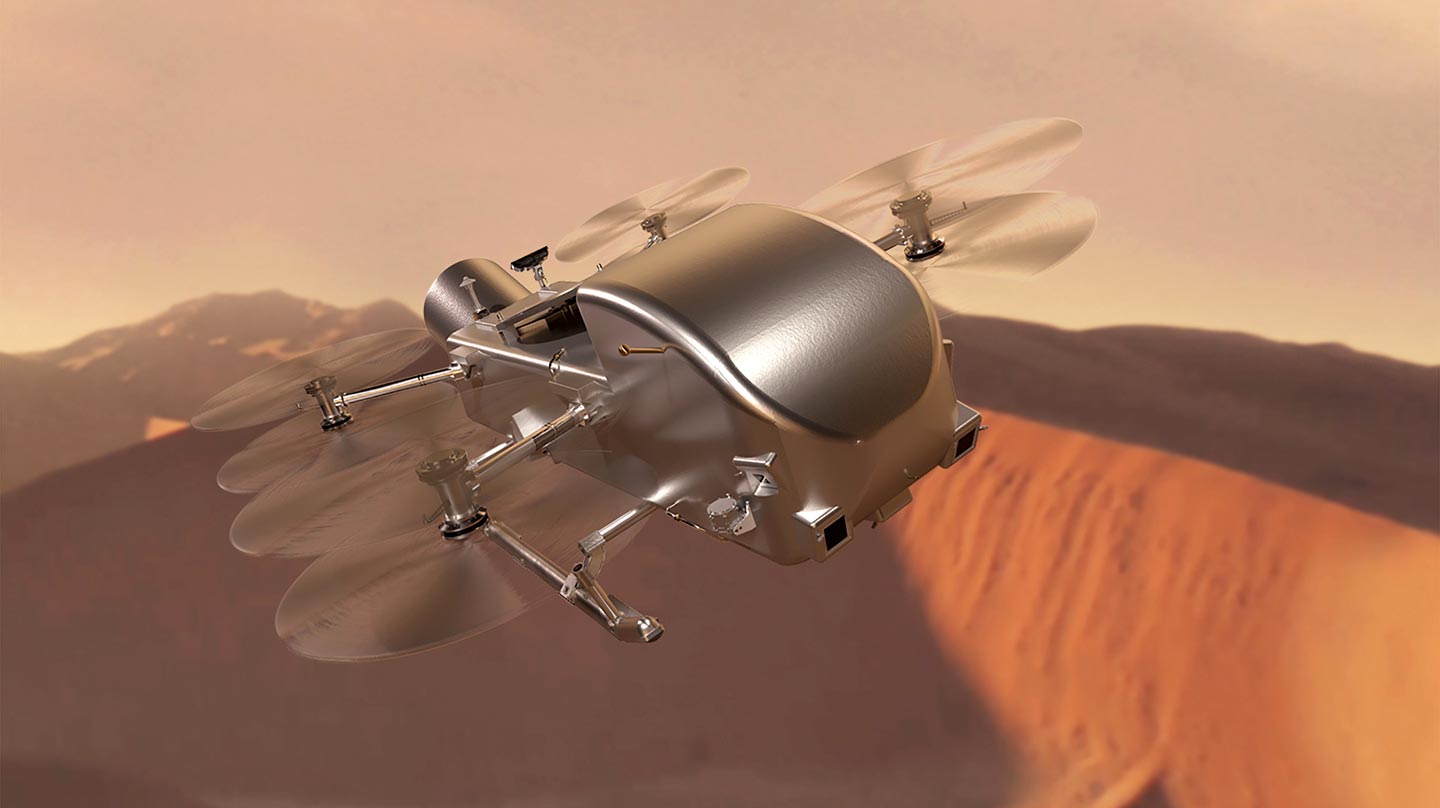

These tests will initially be carried out in Earth orbit over a 24-hour period following launch, during which the Orion vehicle – called Integrity – will lift both the apogee and perigee of its orbit before performing an engine burn to place itself into a trans-lunar injection flight and a free return course out to cislunar space, around the Moon and then back to Earth. The transit time between Earth and cislunar space will be some 4 days (as will be the return transit time). This is slightly longer than Apollo generally took to get to the Moon, but this (again) is because Artemis 2 is not heading directly for a close orbit of the Moon, but rather out to the vicinity of space that will eventually be occupied by Gateway Station, where crews will transfer from their Orion vehicle to their lunar lander from Artemis 4 onwards. Thus, this flight sees Integrity fly a similar profile the majority of Artemis crewed missions will experience.

As I’ve also previously noted, this flight will use a free return trajectory, one which simply sends the craft around the Moon and then back on a course for Earth without the need to re-use the vehicle’s primary propulsion. Most importantly of all, it will test a new atmospheric re-entry profile intended to reduced the amount of damage done to the Orion’s vital heat shield as it comes back through Earth’ atmosphere ahead of splashdown.