The International Space Station celebrated its 25th anniversary on December 6th, 2023 – the date marking the orbital mating of the first two modules forming the station in 1998.

This operation was undertaken by the US space shuttle Endeavour, commanded by astronaut Robert Cabana. Launched on December 4th, 1998 from Launch Complex 39A at Kennedy Space Centre on STS-88, Endeavour carried the US- built Unity module in its cargo bay. Once in orbit, it started a series of manoeuvres to rendezvous with the 19.3 tonne Zarya Functional Cargo Block (referred to as the FGB, this being the Russian funktsionalno-gruzovoy blok), which had been launched out of Baikonur Cosmodrome Site 81 in Kazakhstan on November 20th, 1998.

As Endeavour approached the Russian module, the shuttle’s robot arm lifted the 11.6 tonne Unity node from its cavernous cargo bay and rotating it so that one of the module’s two Pressurized Mating Adapters (PMA) could be attached to the Orbiter Docking System also located in the shuttle’s cargo bay and connected to the shuttle’s airlock.

On reaching Zarya, Cabana then slowly eased Endeavour so it was paralleling Zarya’s orbital track whilst “below” the Russian module. He then gently manoeuvred the shuttle to within 10 metres of Zarya – close enough for Mission specialist Nancy J. Currie, who had mated Unity to the shuttle’s Docking System, to use the shuttle’s robot arm to “grab” the Russian module and gently mate it with the second PMA on the far end of Unity.

EVAs were then conducted by Mission Specialists Jerry Ross and James Newman to connect power and data services between the two modules, and on December 10th, 1998 Cabana and Russian Cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev opened the hatch between the shuttle and the Unity module and entered the latter together as a symbol of US-Russian cooperation, after which members of the shuttle’s crew completed bringing the station’s power and communications systems on-line.

Whilst this marked the first time humans entered the nascent space station, it would not be until November 2001 that the first official crew – Expedition 1 – arrived at the ISS that the station’s “operational” phase would begin, the period between STS-88 and Expedition 1 being regarded as a “construction” period. However, given the latter actually continued well beyond the arrival of Expedition 1, the mating of Unity and Zarya has come to be regarded as the official anniversary of the ISS.

Excluding the astronauts who visited the ISS as a part of STS-88 and those missions ahead of Expedition 1, the space station ISS has hosted 273 individuals from 21 countries around the world. Together they have conducted over 2,500 short- and long-term science experiments and studies involving researchers from 108 countries and multiple disciplines including Earth and space science, educational activities, human research and healthcare, physical science, and technology.

To mark the 25th anniversary, NASA held a special event with the current ISS crew of Expedition 70 – who themselves represent the international nature of the project, as shown below – and special guest Robert Cabana, commander of STS-88.

For Cabana, the event was something of a triple celebration. Not only did it mark space station’s anniversary, but also the 25th anniversary of his 4th and final space mission with STS-88, and the fact that at the age of 74, he is now retiring from NASA. Throughout his later career at the agency, he remained close to the ISS project, joining the Operations team in 1999 to head-up its international aspect, working with other national space agencies. From here he went to work in Russia, heading up NASA’s ISS team there, before becoming the deputy head of the entire ISS project in the US for a two-year period through to 2004. After this he served as the Director of Flight Crew Operations, all the while maintaining his “active” flight status as an astronaut. In May 2021, after stints managing various NASA facilities – including Kennedy Space Centre -, Cabana was promoted to NASA Deputy Administrator, one of 16 former US astronauts holding senior management roles in the agency, the post from which he will now be retiring.

The event itself was a little dry, but also fascinating in the way to shone a light on the astronauts themselves in terms of their thoughts on living and working in space and what captivates them.

The celebration of the space station’s 25th anniversary came alongside the news that NASA is revising contract options and timings for the station’s “retirement”. This is due to come in late 2030 or early 2031, when the ISS will be de-orbited in a controlled manner so that it will break-up on entering the upper atmosphere, with any large elements falling into the South Pacific.

Originally, it had been planned to announce the contract for building the de-orbit vehicle at the end of 2023. However, this has now been pushed back until February 2024, the additional time to allow prospective bidders for the contract to review its updated options, which have been altered from a fixed-price basis to something a little more flexible.

This new contract calls for the de-orbit vehicle to be ready for launch no later than mid-2029, so that it can be launched to dock with the ISS where it will remain until called upon to de-orbit the station. Whilst planned for the end of 2030 / start of 2031, the new contract requires the vehicle must have “dwell in place” capability, allowing it to remain docked at the station but capable of performing its task for a period beyond 2031 so as to provide increased flexibility in the time frame for the decommissioning and de-orbit of the station.

Blue Origin to Purchase ULA?

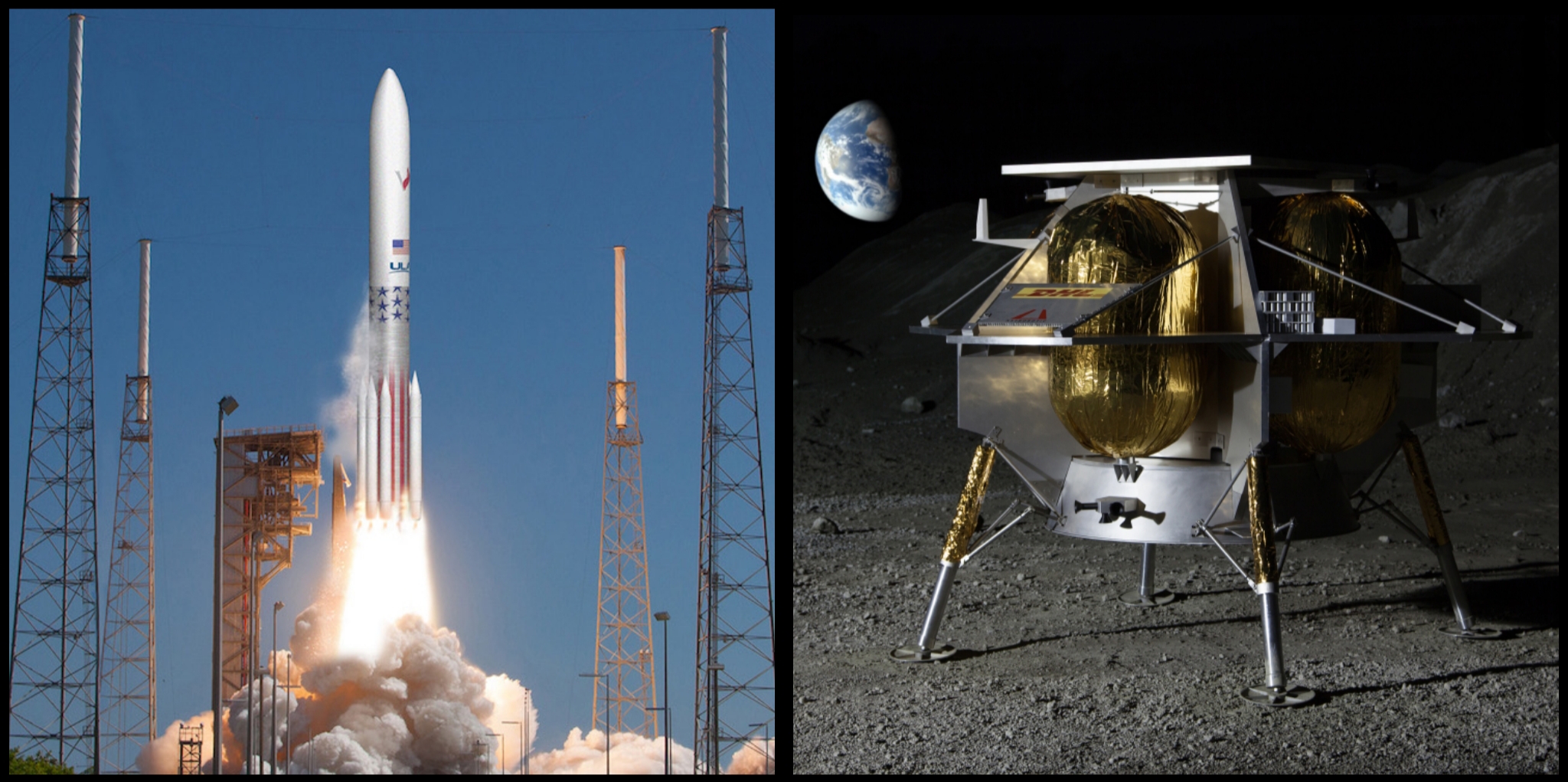

United Launch Alliance (ULA) is something of the “granddaddy” of US government launch system providers. A joint venture between Lockheed Martin Space and Boeing Defense, Space & Security, it was formed in 2006 with its primary customers being the US Department of Defense (DoD) and NASA, proving them with the expendable Delta IV Heavy and Atlas V boosters and which will soon be replaced by ULA’s new Vulcan Centaur rocket.

However, at the end of October 2023, ULA’s current CEO Tory Bruno indicated the entire company could available for purchase by anyone willing to obtain it as a going concern, rather than breaking it up, stating the overall structure of the company – answerable in equal portions to the two parent companies – has prevented the company from flourishing as well as it could if under single ownership.

Prior to Bruno’s announcement it had been rumoured that either Boeing or Lockheed would buy the other out, but neither appeared willing to do so, each pursuing its own space contracts. As a result, and at the end of November 29th, 2023, it appeared that three bidders had expressed an interest in taking over ULA – although one has yet to be confirmed.

Th “possible” bidder has been referred to as a “well-capitalized aerospace firm that is interested in increasing its space portfolio” but which “does not have a large amount of space business presently”. Meanwhile the two “known” organisations interested in ULA are said to be a private equity fund – and Blue Origin, the privately-owned company founded (and largely funded) by billionaire Jeff Bezos.

The idea of Blue Origin gobbling up ULA might seem inconceivable, but there is actually a lot of synergy between the two already: Blue Origin has worked closely with ULA in the development of the company’s BE-4 engine which will be used to power ULA’s Vulcan Centaur and upgraded Atlas V (as well as Blue Origin’s own New Glenn).

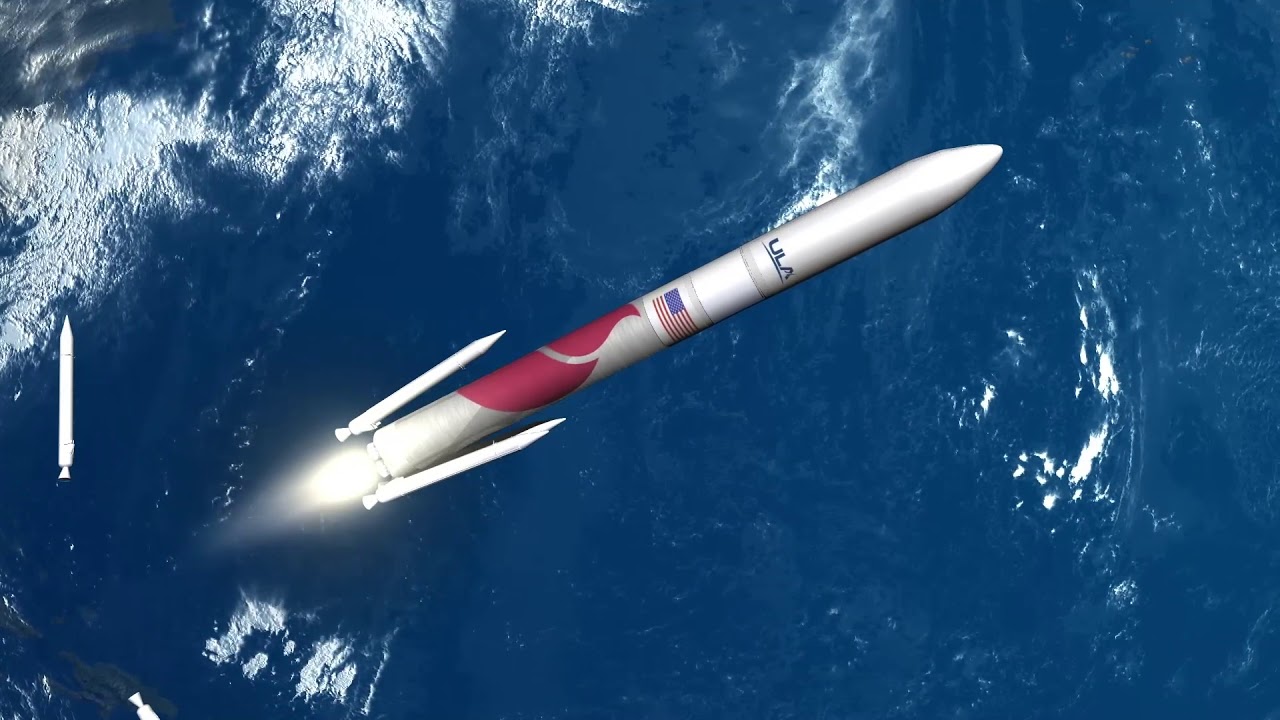

Further, Vulcan Centaur’s capabilities overlap nicely with those of New Glenn, offering Blue Origin with a broad range of launch capabilities. ULA has also sought to eventually make Vulcan Centaur semi-reusable, the engine module being detached from the rocket’s first stage and recovered after splashdown, allowing it to be refurbished and re-used. Such a capability would both dramatically reduce operating costs with Vulcan Centaur – and also match Blue Origin’s desire to develop semi-reusable launch systems, as with its New Glenn. So again, there is a synergy here.

Perhaps most beneficial to Blue Origin is that an acquisition of ULA is the fact that the latter is already an establish provider of launch vehicles to the lucrative US defence market, which Blue Origin could then capitalise upon. In addition, ULA’s Atlas V and the Vulcan Centaur launches are designed to carry humans into space via the Boeing CST-100 Starliner capsule. Thus, Blue Origin gain the means to fly crews into space in partnership with Boeing – potentially vital to its space station plans.

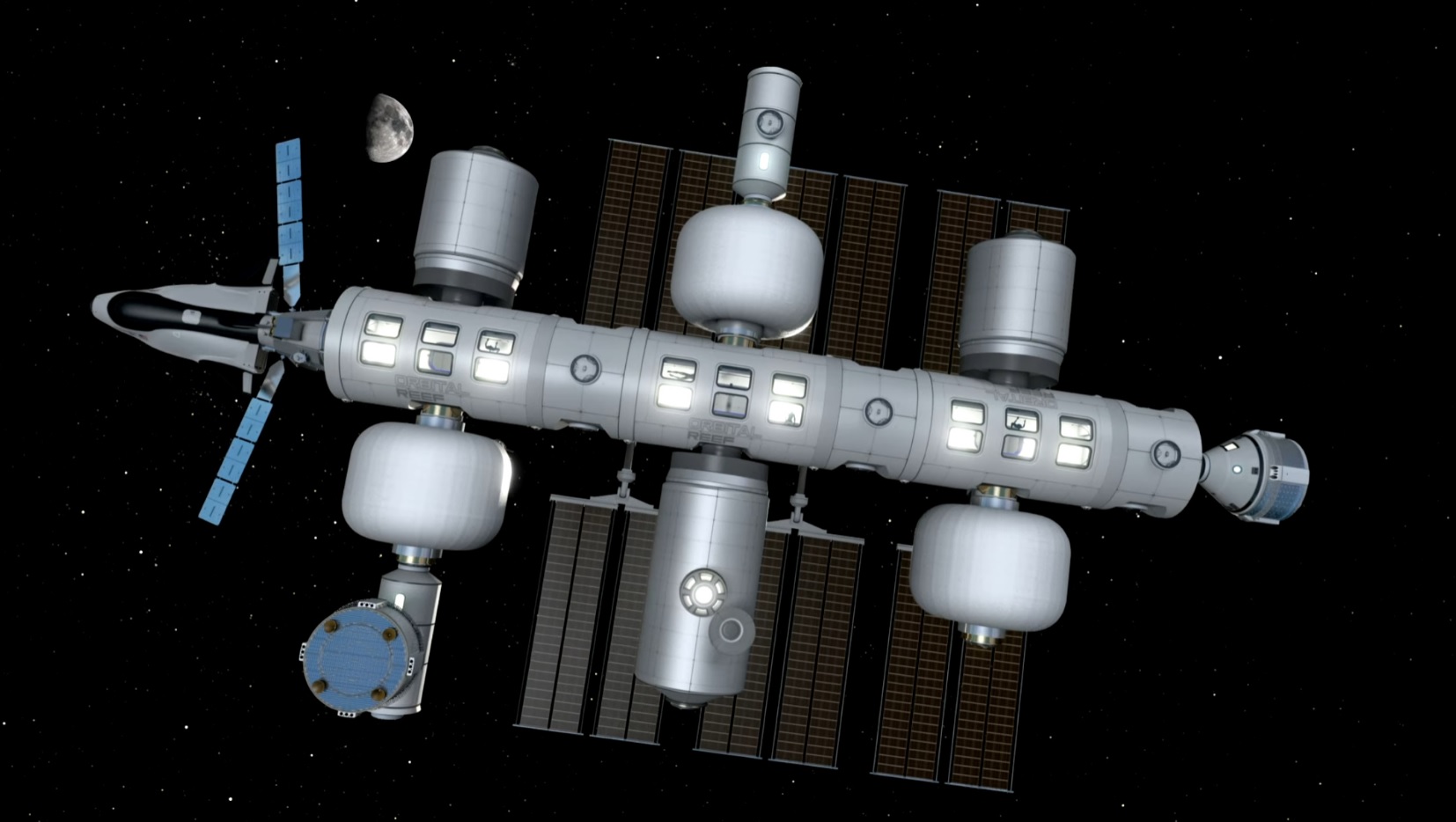

In 2021, Blue Origin and Sierra Space announced plans for an orbital facility called Orbital Reef, designed to provide facilities for up to 10 people at a time. Under current plans, Blue Origin would provide the station’s large-diameter modules and the launch vehicle (New Glenn), Sierra Space the smaller modules and cargo support via their Dream Chaser vehicle, and Boeing / ULA crew launch capabilities via Starliner / ULA launchers. If Blue Origin obtained ULA, it would further streamline Orbital Reef development / operations. Plus, being able to fly the CST-100 via the Atlas and Vulcan Centaur allows Blue Origin to access a share of NASA’s crewed launch requirements to service the ISS, again through Boeing.

Thus far, neither Boeing nor Lockheed have either confirmed or denied whether ULA is in fact up for sale – but industry insiders believe an announcement on the state of play with ULA – including any winning bid – will be made in early 2024. However, exactly how long any acquisition might take to complete is also unclear, requiring as it would the approval via the US Federal Trade Commission.

Continue reading “Space Sunday: ISS reaches 25; HST resumes mission”