Curiosity should be resuming the characterisation phase tests following the upgrading of the on-board computer systems to the R10 flight package. Following the upgrade, NASA hosted a teleconference in which it was indicated the software transition proceeded smoothly and successfully.

Curiosity should be resuming the characterisation phase tests following the upgrading of the on-board computer systems to the R10 flight package. Following the upgrade, NASA hosted a teleconference in which it was indicated the software transition proceeded smoothly and successfully.

This week will see the REMS system commence continuous operations, so mission scientists are hoping to get the first complete 24+ hour Sol cycle of weather data returned later in the week. The mission planners are also looking to run another series of high-resolution images of “Mount Sharp”, right up to the peak of the mound, now that the rover’s orientation relative to the ground and the Sun are understood.

With the successful software transitioning, the characterisation phase for the rover now enters stage 1b characterisation (the first week having been 1a characterisation). This will see more of the rover’s science systems enter operation, and preparations made for Curiosity’s first drive. This will be preceded on Sol 13 by a static test of the rover’s steering actuators. The initial drive – probably no more than a few metres and turning the rover in an arc – is currently scheduled for Sol 15.

It is estimated that the 1b characterisation phase will last a couple of weeks, and should result in everything aboard the rover being declared as commissioned and ready for operations with the exception of the robot arm and hand. These will be tested during a third characterisation phase (called “characterisation 2”), which is still around a month away. In the period between the end of characterisation 1b and characterisation 2, the rover will be commencing an initial set of science operations using its other instruments.

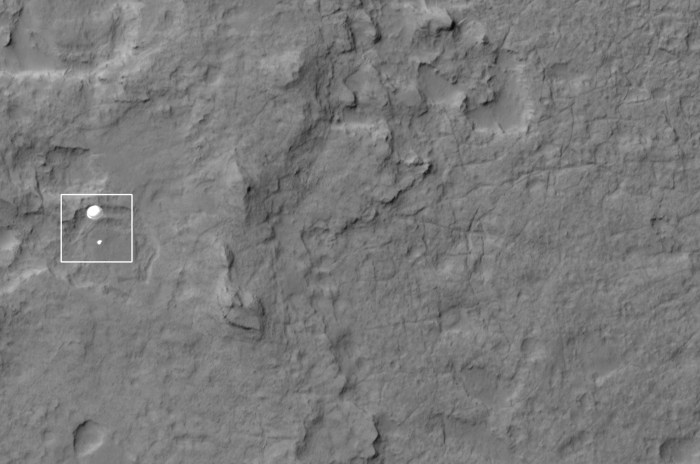

As it stands, mission staff are already building up a plan for the rover’s traverse from the landing zone to the slopes of “Mount Sharp”. The mound is only around 8 kilometres (5 miles) from the rover, but the route will not be direct, and there are a number of mesas the rover must navigate around – and which may themselves have points of interest to be investigated, although the aim is to get the rover into the ravines cutting into the slopes of the mound, rather than in diversions elsewhere.

Mission Trivia: Does Curiosity Dream of Electric Sheep?

To conserve power, Curiosity has what is called a “sleep state” in which the main computers are hibernating and systems are largely running in a minimal state. During this time, monitoring the rover’s status and condition is the responsibility of a small monitoring system independent of the rover’s computers. JPL engineers refer to the data returned from this unit (the MRU) as Curiosity’s “dream state”.

See Gale crate for Yourself

Want to see Gale Crater exactly as Curiosity sees it as the Mastcam is rotated through 360-degrees? Want the ability to zoom in and out of images and have a look at the rover itself?

Photographer Andrew Bodrov has taken images captured by Curiosity’s Mastcam last week and put them into a superb 360-degree interactive panorama, allowing you to see Gale Crater, the surface of Mars and the rover itself in marvellous detail (the images of the rover used here are captured from the view).

To take a look for yourself, visit the 360cities.net website (unfortunately, WordPress.com blew a raspberry at attempts to embed the view here).

With thanks to MartinRJ Fayray for info on the 360cities interactive display.