Astronomy is a field of observation / science / study that is pretty much open to anyone with a passion and understanding of things celestial to make a contribution, whether amateur or professional in the field.

Take Hideo Nishimura, for example. As an amateur astronomer living in Kakegawa, Japan, he decided to take advantage of the clear skies overhead on August 11th, 2023 and take some photographs of the sky using his telescope and imager. It wasn’t the first time he’s done this – like many other amateur astronomers he gets enormous pleasure out of imaging and studying the night sky. However, the results caused a little more excitement than expected in the Nishimura household when Hideo noticed that in one of his images, taken towards the direction of the setting Sun showed an object that shouldn’t have been there. After contacting the International Astronomical Union, which followed-up his observations via the Minor Planet Centre, Hideo was informed he has discovered a comet making what is likely to be its first – and only – passage through the inner solar system.

Now called C/2023 P1 Nishimura in his honour, the comet is believed to be an object originating in the Oort cloud, and was knocked out of its distant orbit around the Sun by collision or some other interaction, and has been gradually “falling” towards the Sun ever since.

Such objects are not uncommon – the “C” in the title of such objects indicates they likely originate from the Oort cloud and either end up passing through the solar system and long-period comets (i.e. taking anything from a couple of hundred years to several thousand to loop around the Sun) such as C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) seen at the top of this article. However, occasionally, some end up accumulating sufficient velocity during their inward “fall” towards the Sun that rather than looping around it and staying in an elongated orbit, they are accelerated like a pebble out of a slingshot, escape the Sun’s influence altogether, to eventually vanish into interstellar space.

And that’s exactly what C/2023 P1 Nishimura looks set to do (the 2023/P1 in the title indicated its year of discovery and the fact it was the first such object to be discovered in the first half of August (the IAU splitting the months in two alphabetically for objects like comets – So January 1th through 15th is A; then January 16th to 31st is B, with February 1st through 15th C, and so on, with both I and Z ignored to avoid confusion with 1 and 2).

Currently, the comet is at a magnitude of around 9.4, meaning it can only be seen using telescopes of 15cm or larger. However, as it approaches the Sun, it is expected to grow much brighter, potentially becoming visible to the naked eye at around a magnitude of 4.9 in the period September 10-15th (during which time it will be at its closest to Earth, around 0.85 AU distant) and may by that time demonstrate a tail.

Between September 10th and 12th, period, the comet will be visible for a few hours before dawn in the constellation Leo. From September 13th, it will transition to being an evening object visible immediately after sunset. It will reach perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) on September 18th, when it will appear to be in the constellation of Virgo, about 12° away from the Sun. Perihelion is also the point at which C/2023 P1 Nishimura faces its greatest threat: in passing around the Sun, it is possible the differential forces of its acceleration and the Sun’s gravity might cause it to break up.

Following perihelion the comet will start to move away from the Sun – and out of the solar system – offering those in the northern hemisphere with perhaps the best opportunities to view it, although it will diminish in brightness quite rapidly, and once again require a telescope to see it from October onwards.

Those who are interested in astronomy and use apps as an adjunct to their skywatching might like to know that both Sky Tonight and Star Walk 2 apps (the latter may require the purchase of an add-on), provide the comet’s trajectory and brightness in real-time, giving you the most accurate and up-to-date information on where to view it

These are some of the upcoming dates for observations. Note that use of naked eye, binoculars, etc., and visibility in general dependent on factors such as eyesight, location, amount of light pollution, etc.):

| Date | Magnitude / Visibility | Approx location / status |

| August 26 | 9.2 – telescope | Enters the constellation Cancer |

| September 5 | 6.9 – binoculars with 7x magnification or above | Enters the constellation Leo |

| September 7 | 6.3 – binoculars / possibly naked eye | Passes 0°16′ away from the star Ras Elased Australis (mag 3.0) in the constellation Leo |

| September 9 | 6.3 – binoculars / possibly naked eye | Passes 0°20′ away from the star Adhafera (mag 3.4) in the constellation Leo |

| September 9 | 5.6 – binoculars / possibly naked eye | Passes 0°20′ away from the star Adhafera (mag 3.4) in the constellation Leo |

| September 13 | 4.3 – naked eye | Reaches its closest approach to the Earth at a distance of 0.29 AU in the constellation Leo |

| September 15 | 3.7 – naked eye | Passes 0°10′ away from the star Denebola (mag 2.1) in the constellation Leo |

| September 16 | 3.4 – naked eye | Enters the constellation Virgo |

| September 18 | 3.2 – naked eye | Reaches perihelion the constellation Virgo (do not use optical aids when looking towards the Sun while it is above the horizon) |

| September 22 | 4.3 – naked eye | Passes 1°30′ away from the star Porrima (mag 2.7) in the constellation Virgo |

Lunar Missions Update

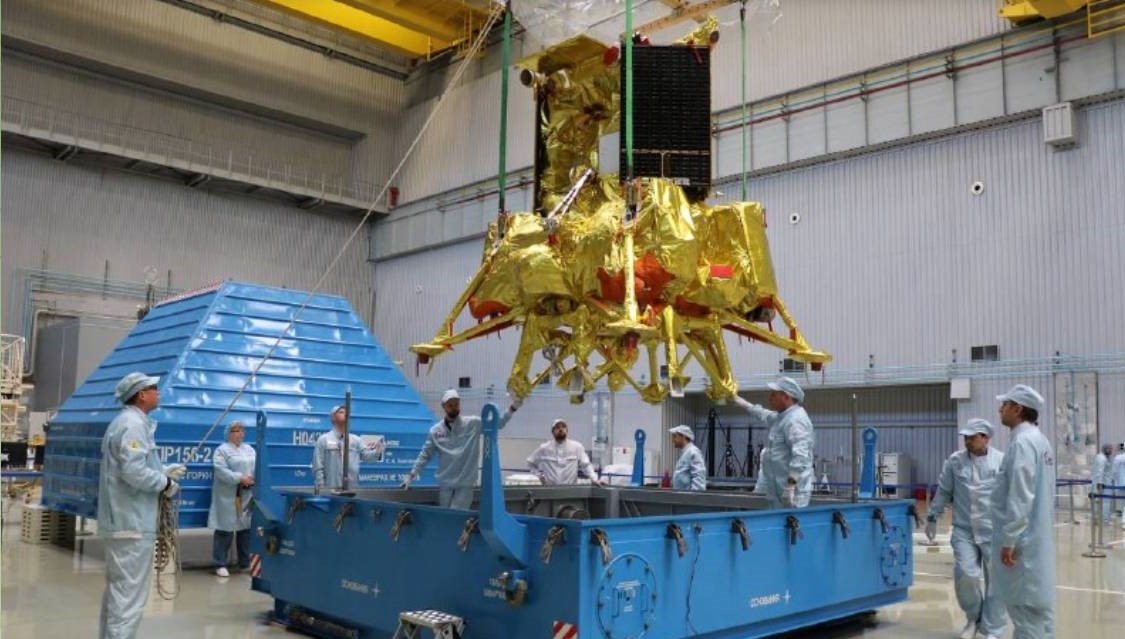

My recent Space Sunday pieces have been in part covering two robotic missions to the surface of the Moon – India’s Chandrayaan-3 and Russia’s Luna-25.

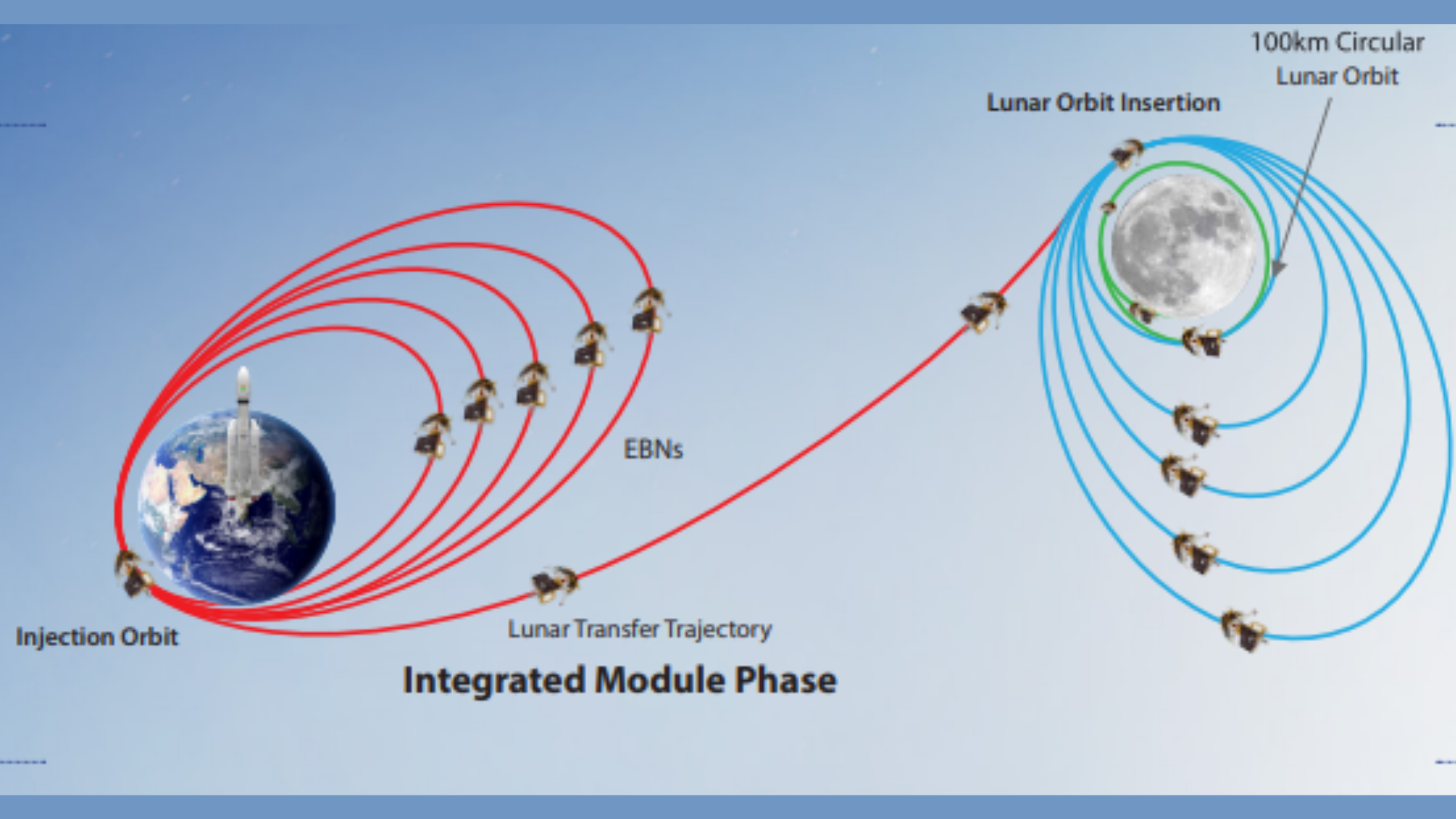

Whilst having launched almost a month after Chanrayaan-3, Luna-25 – by dint of using a more powerful launch vehicle coupled with a somewhat more direct (“spiral”) flight to the Moon – actually arrived in a position from which a landing attempt could be made first.

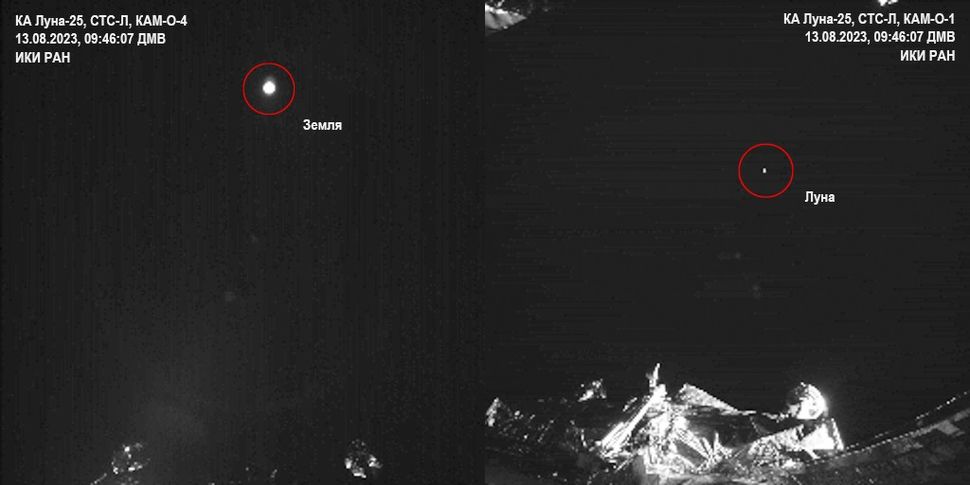

Thus, on August 19th, 2023 (UTC) the Russian lander – which had performed flawlessly throughout the mission to this point – commenced an engine burn which unfortunately did not go well.

Thrust was released to transfer the probe onto the pre-landing orbit During the operation, an emergency situation occurred on board the automatic station, which did not allow the carrying out of the manoeuvre within the specified conditions.

– Roscosmos statement on Luna-25 released via Russia’s Telegram messaging service

The command to start the manoeuvre was sent at 23:10 UTC on August 19th, the engine burn intended to orient and position the vehicle ready for a decent and landing on August 21st. However, direct communications with the vehicle were lost at or around 23:57 UTC.

Later on August 20th, Roscsomos issued an update in which it was confirmed that all attempts to re-establish communications contact with the vehicle had failed, and the a preliminary review of the flight data received prior to contact terminating suggested the craft had deviated from its flightpath during the engine burn sufficiently that it afterwards crashed into the Lunar surface – although at the time of writing, investigations into the loss were obviously still very much in the initial phases.

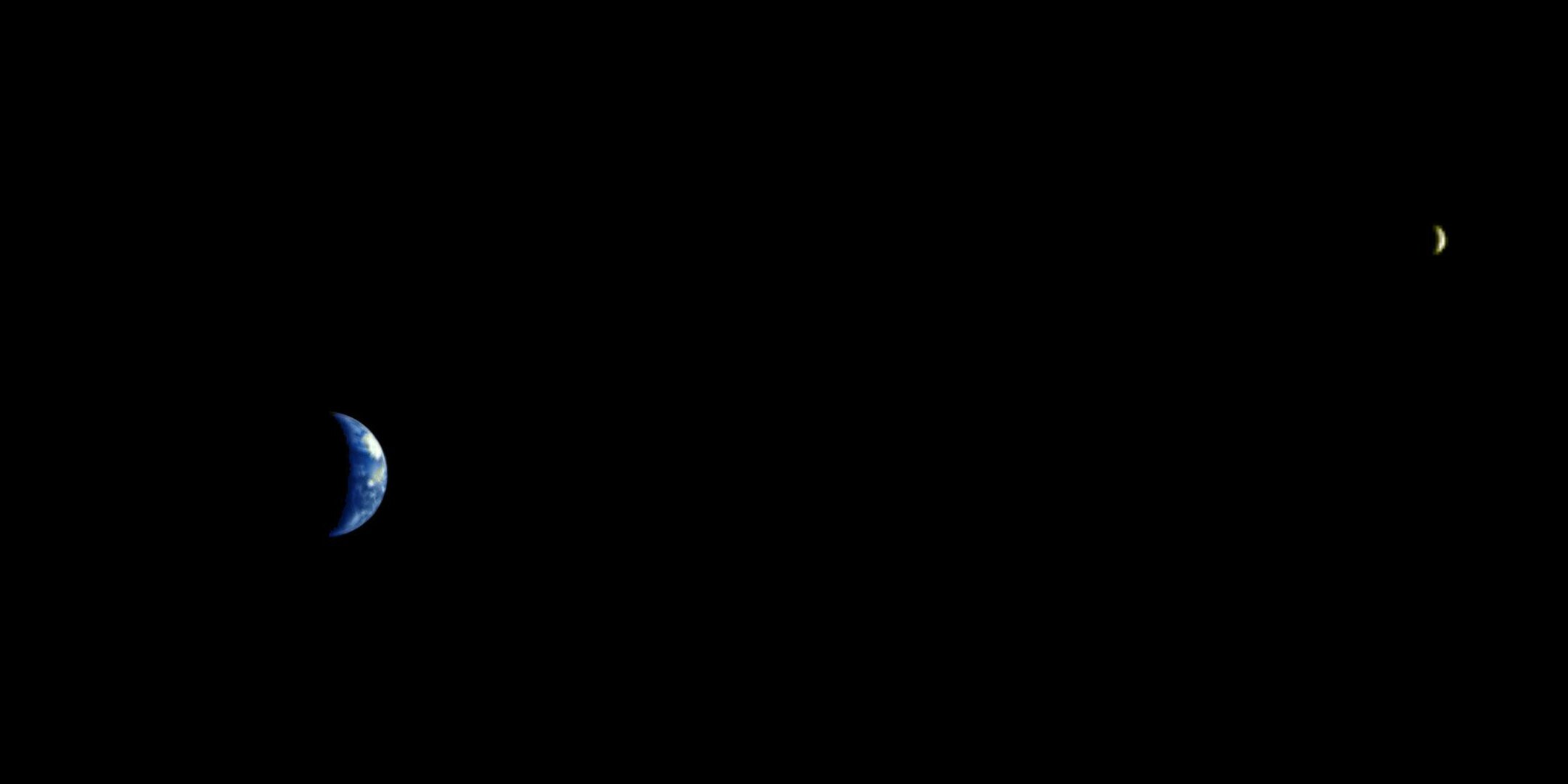

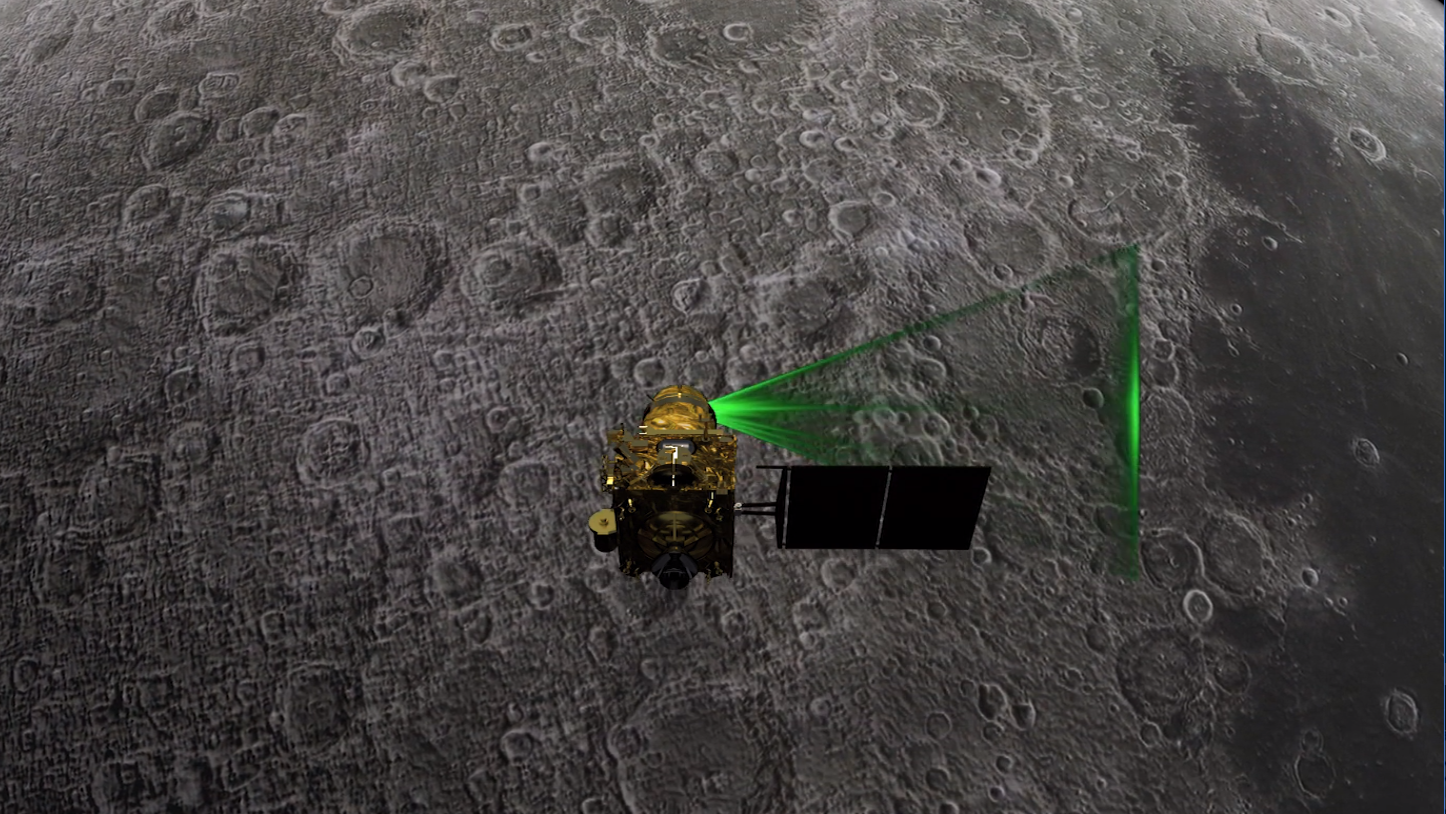

Meanwhile, on August 17th, the Chanrayaan-3 lander / rover combination launched by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) in July successfully separated from their propulsion module, 12 days after initially arriving in an extended lunar orbit. Separation placed the lander / rover combination under their own power and allowed them to start their final set of manoeuvres in preparation for a descent and landing. The first of these was performed on August 19th, when the Vikram lander made the first of the small adjustments needed to bring it down to the 100 km altitude from which the landing attempt will be made on August 23rd.

In PR terms, both of these missions are relatively “high stakes” for both Russia and India. Chanrayaan-3 is intended to overcome the loss of the lander/rover combination which crashed onto the Moon on September 6th, 2019 as a part of the highly ambitious Chanrayaan-2 mission. That loss still overshadows the fact that the third element of the mission, the lunar orbiter, continues to orbit the Moon carrying out its own very successful science mission. In this, it will be joined by the Chanrayaan-3 propulsion module, which although not by definition a satellite, nevertheless carries a small suite of instruments intended to study Earth’s atmosphere from afar, and – according to the ISRO – also scan exoplanets to assess their potential for habitability.

Luna 25, meanwhile, was intended to herald Russian’s return to independent deep-space exploration 47 years after its last lunar mission (Luna-24) and 34 years since its last attempt at an interplanetary mission (Phoboos 2) – both of which were soviet-era missions. It was also intended to demonstrate Russia’s ability to be a major player in the China-led International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) – the launch of the mission even having one of the senior Chinese officials for that programme, Wu Yanhua present.

These are far from the only missions heading for the Moon over the next few years. Japan, for example, is due to launch its Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) vehicle on August 25th (UTC). This is a technology demonstrator designed to make exploration more precise and economical, and which is cadging a ride on the H-IIA launch of Japan’s X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM, pronounced “crism”) space telescope.

Unlike Luna 25 and Chanrayaan-3, SLIM will not be going to the lunar South Pole, but will be heading for a group of volcanic domes located in Oceanus Procellarum, 18oN of the lunar equator, where it will attempt to guide itself to a landing close to the Marius Hills Hole, a lunar lava tube entrance. Nevertheless, its landing will be as challenging as those for any mission to the Moon, and the loss of Luna 25 reminds us that lunar exploration is still a hazardous undertaking.

Also heading to the Moon – this time in November – will be Nova-C lander, the first private mission to the Moon to be carried out by Intuitive Machines under the mission title IM-1. Selected as a part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) programme, the mission will deliver a suite of science instruments and mini-rovers to at Malapert A near the lunar south pole. I’ll likely have more on this mission and Japan’s XRISM and SLIM in a future update.