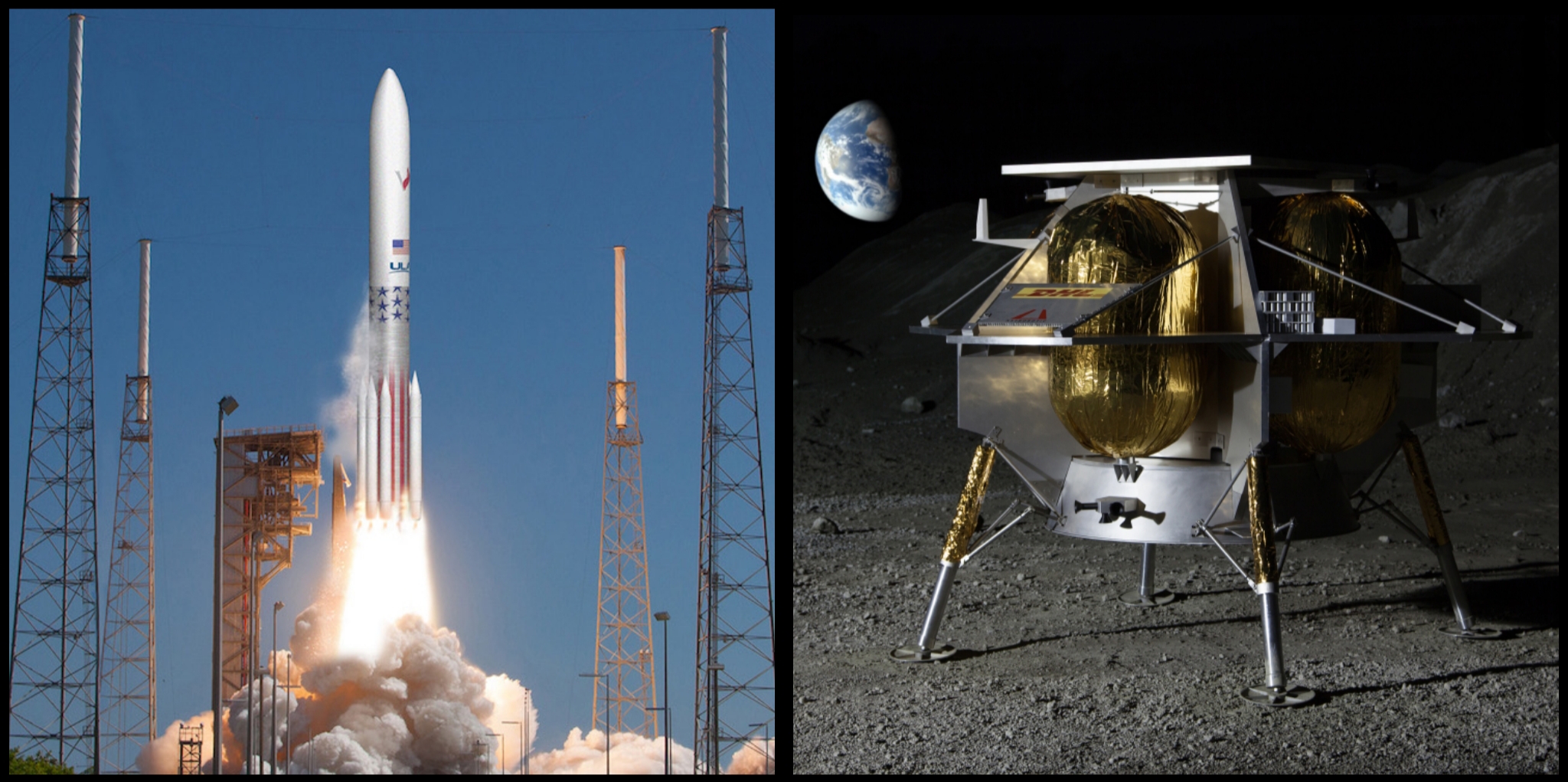

America’s return to the surface Moon as a part of government-funded activities will start in earnest over Christmas 2023, with the launch of the NASA-supported Peregrine Mission One and the Peregrine lander, built by Astrobotic Technology, which will take to the sky on December 24th, 2023 atop a Vulcan Centaur rocket out of Cape Canaveral Space Force Base, Florida.

Originally a private mission, Mission One qualified for NASA funding under the agency’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) in 2018, effectively making it the first lander programme funded by NASA under the broader umbrella of the Artemis programme. In this capacity, the mission will fly 14 NASA-funded science payloads in addition to the original 14 private payloads planned for the mission.

The mission will be the inaugural payload carrying flight for the Vulcan Centaur, with the lander arriving in lunar orbit after just a few days flight – but will not land until January 25th, 2024, the delay due to the need to await the having to wait for the right lighting conditions at the landing site.

I’ll have more on this mission closer to the launch date, but in the meantime, as the Peregrine Mission One launch date is getting closer, the date for America’s return to the Moon with a crewed mission is slipping further away.

In terms of the Artemis crewed programmed, there have been a number of flags raised around the stated time-frame for Artemis 3, the mission slated to deliver the first such crew to the surface of the Moon in 2025, over the past few years. These have notably come from NASA’s own Office of Inspector General (OIG), but similar concerns have also started to be more openly voiced from within NASA.

These concerns largely focus on whether or not SpaceX can provide NASA with its promised lunar lander and its supporting infrastructure in anything like a timely manner, given that SpaceX has yet to actually successfully fly a Starship vehicle. In this, the awarding of the lander vehicle – called the Human Landing System (HLS) in NASA parlance – to SpaceX, who propose using a specialised version of the Starship vehicle, was always controversial. For one thing, Starship HLS will be incapable of being launched directly to lunar orbit. Instead, it will have to initially go to low Earth orbit and reload itself with propellants – which will also have to be carried to orbit by other Starship vehicles.

At the time the contract for HLS was awarded (2021), competing bidders Blue Origin noted that according to SpaceX’s own data for Starship, a HLS variant of the vehicle would require the launch of fifteen other starship vehicles just to get it to the Moon. The first of these would be another modified Starship designed to be an “orbiting fuel depot”. It would then be followed by 14 further “tanker” Starship flights, which would transfer up to 100 tonnes of propellant per flight for transfer to the “fuel depot”. Only after these flights had been performed, would the Starship HLS be launched – and it would have to rendezvous with the “fuel depot” and transfer the majority of propellants (approx. 1,200 tonnes) from the depot to its own tanks in order to be able to boost itself to the Moon and then brake itself into lunar orbit.

Despite such claims being made on the basis of SpaceX’s own figures, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk pooh-poohed them, claiming all such refuelling could be done in around 4-8 flights, not 16. Despite their own OIG and the US Government Accountability Office (GOA) agreeing with the 16-flight estimation, NASA nevertheless opted to accept Musk’s claim of 4-8 launches, going so far is to use it in their own mission graphics.

However, the agency appeared to step back from this on November 17th, 2023, when Lakiesha Hawkins, assistant deputy associate administrator in NASA’s Moon to Mars Programme Office, confirmed that SpaceX will need “almost 20” Starship launches in order to get their HLS vehicle to the Moon, with launches at a relatively high cadence to avoid issues of boil-off occurring when storing propellant in orbit.

Now the US Government Accountability Office (GOA) has re-joined the debate, underlining the belief that SpaceX is far from being in any position to make good on its promises regarding the available of HLS. In particular the report highlights SpaceX is still a good way from demonstrating it can successfully orbit (and re-fly) a Starship vehicle, and it has not even started to demonstrate it has the means to store upwards of 1,000 tonnes of propellants in orbit, or the means by which volumes of propellants well above what has thus far been achieved can be safely and efficiently be transferred between space vehicles, and it has yet to produce a even a prototype design for the vehicle.

Nor does the report end there; it is also highly critical of the manner in which NASA has managed the equally important element of space suit design, firstly in awarding the initial contract for the Artemis lunar space suits to Axiom Space – a company with no practical experience in spacesuit design and development – rather than a company like ILC Dover, which has produced all of NASA’s space suits since Apollo; then secondly in failing to provide Axiom with all the criteria for the suits, necessitating Axiom redesigning various elements of their suit to meet safety / emergency life support needs.

As a result, the GAO concludes that it is likely Artemis 3 will be in a position to go ahead much before 2027; there is just too much to do and too much to successfully develop for the mission to go ahead any sooner. In this, there is a certain irony. When Artemis was originally roadmapped, it was for a first crewed landing in 2028; however, the entire programme was unduly accelerated in 2019 by the Trump Administration, which wanted the first crewed mission to take place no later than December 2024, so as to fall within what they believed would be their second term in office. Had NASA been able to stick with the original plan of 2028, there is a good chance that right now, it would be considered as being “on target”, rather than being seen as “failing” to meet time frames.

Hubble Hits Further Gyro Issues

On November 29th, 2023, NASA announced that the ageing Hubble Space Telescope (HST) had entered a “safe” mode for an indefinite period due to further troubles with the system of gyroscopes used to point the observatory and hold it steady during imaging.

In all, HST has six gyroscopes (comprising 3 pairs – a primary and a back-up),with one of each pair required for normal operations. To help increase the telescope’s operational life, all three pairs of gyros were replaced in the last shuttle mission to service Hubble in 2009, and software was uploaded to the observatory to allow it to function on two gyros – or even one (with greatly reduced science capacity) should it become necessary.

Today, only 3 of those gyros remain operational, the other three having simply worn out, and on November 19th, one of those remaining 3 started producing incorrect data, causing the telescope to enter a safe mode, stopping all science operations. Engineers investigating the issue were able to get the gyro operating correctly in short order, allowing Hubble to resume operations – only for the gyro to glitch again on November 21st and again on November 23rd, leading to the decision to leave the telescope in its safe mode until the issue can be more fully assessed.

The news of the problems immediately led to renewed calls for either a crewed servicing mission to Hubble or some form of automated servicing mission – either of which might also be used to boost HST’s declining orbit. However, such missions are far more easily said than done: currently, there isn’t any robotic craft capable of servicing Hubble (not the hardware or software to make one possible). When it comes to crewed missions, it needs to be remembered that Hubble was designed to be serviced by the space shuttle, which could carry a special adaptor in its cargo bay to which Hubble could be attached, providing a stable platform from which work could be conducted, with the shuttle’s robot arm also making a range of tasks possible, whilst the bulk of the shuttle itself made raising Hubble’s orbit much more straightforward.

Currently, the only US crewed vehicle capable of servicing HST is the SpaceX Crew Dragon – and it is far from ideal, having none of the advantages or capabilities offered by the space shuttle, despite the gung-ho attitude of many Space X supporters. In fact, it is not unfair to say that having such a vehicle free-flying in such close proximity to Hubble, together with astronauts floating around on tethers could do more harm than good.

A further issue with any servicing mission is that of financing. Right now, the money isn’t in the pot in terms of any funding NASA might make available for a servicing mission – and its science budget is liable to get a lot tighter in 2024, which could see Hubble’s overall budget cut.

The Perfect Celestial Dance of the Little Neptunes

HD 110067 is a K0V main sequence star some 100 light-years from Earth, located within the constellation of Coma Berenices. This category of star which is on average slightly smaller and cooler than our own Sun, but with a similar level of stability and longevity, marking them as being of particular interest in the search for other planetary systems.

In this regard, HD 110067 has been the subject of study by the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExOPlanets Satellite), operated by NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) respectively, with both space observatories locating six planets in orbit around it.

All six are referred to as sub-Neptunian planets, meaning they are all somewhat smaller than our own Neptune, with masses of between 3.9 times and 8.5 times that of Earth (Neptune being around 17 times Earth’s mass). All are in orbits fairly close to their parent star with the furthest out (HD 110067g) completing an orbit once every 54.69 terrestrial days, and the nearest (HD 110067b) completing an orbit in just 9.113 terrestrial days.

However, what is particularly fascinating is that all six planets are in a very precise dance one to the next around their parent star. Two pairs of three – b and c, c and d and d and e, all orbit with a resonance of 3:2. That is, for every three orbits completed by the innermost of each pair (say b) the outer member of the pair (in this case c) completes two orbits. Meanwhile two pairs (e and f, and f and g) orbit with resonances of 4:3 (that is, for every 4 orbits e completes, f completes 3, and the same for f and g), whilst the resonance between the innermost planet (b) and outermost (g) is exactly 6:1.

Orbital resonances between young planets as they orbit stars are not uncommon; however, due to a range of factors, they tend not to survive for extremely long period. Things like the gravitational action of other planets in the system, or a natural migration away from their original orbits tend to interfere with such resonances, altering them over time. In fact, it is estimated that planetary systems demonstrating any resonance at all account for perhaps just 1% of all planetary systems in our galaxy.

Give estimates suggest HD 110067 is around the same age as our Sun, the fact that its planets have retained a pristine set of resonances throughout that time makes it a truly unique system. That it exists so close to our own world means it is now a ideal case study, one which may help us discover more about the nature of how planetary systems are formed, and their potential to support either life or the elements required by life. As such, HD 110067 and its planets have already been earmarked for detailed study by the James Webb Space Telescope.

The Planet To big for Its Sun

We’re probably all familiar with the model on star and planetary system formation. Referred to as either the core accretion theory or the nebular hypothesis, this holds that star systems commence as a rotating cloud of gas, around 98% of which coalesces and compacts, mass and gravity drawing it down until the pressure is so great, hydrogen atoms at the heart of the mass fuse, and nuclear ignition occurs and a star is born.

This act tends to leave a disk of material spinning around the star, elements of which in turn start to accrete and form small rocky bodies which then grow into boulders, then to planetismals, then protoplanetary cores, and so on until they are large enough to sweep up matter from the disk and form planets both solid and gaseous.

These concepts are something we can all get our heads around, but hidden within them is a little point of interest: by-and-large there is a degree of correlation between the mass of a star and the mass of any accretion disk left after its formation from which planets might later form, which astronomers can calculate and model with a reason degree of certainty. Or that’s the theory.

Enter LHS 3154. This is a small, M-class star – the most common and oldest type of star in the galaxy. It is nine times less massive than the Sun, and so by rights should have had a very low mass accretion disk left spinning around it after nuclear fusion imitated, limiting the size or number (or both) of planets which might then form.

And LHS 3154 does have a planet, imaginatively called LHS 3154b. But here’s the rub: It is close to the mass of Neptune, and calculations show that it would have required an accretion disk around ten times more massive than would have likely existed around LHS 3154 in order to have formed. In other words, it is actually too big for its parent star, and shouldn’t exist where it does.

Currently, the team responsible for studying LHS 3154b have no explanation for its existence or how it came to be so close to its parent (massive planets orbiting close to M-class stars like LHS 3154 are also extremely rare); however their work is again revealing that as much as we discover about the galaxy and universe at large, the more we have yet to understand.

I’m amused by Elon’s bravado. He speaks like a promoter at a press conference. I’m so fond of the saying, “If it was that easy, it would be done by now.”

It is better to err on the side of caution and all that. I’d rather be late and right than early and wrong. Late? You’re only late if the original plan underestimated the time necessary.

LikeLike

Too many people drink from the font of Musk Kool-aid rather than looking long and hard at his actual track record on delivery. In terms of SpaceX he has a lot of undeserved credit for the company’s success – the majority of which in truth is down to the likes of the now-departed Tom Mueller, who with his team of actual engineers literally propelled the company to success with the design and development of the Merlin engine family which power the Falcon family of boosters as well as helping inform their design and capability.

LikeLike