On August 23rd, 2023, India became the 4th nation to successfully land a vehicle on the Moon, after Russia, the United States and China – and the first nation to manage to do so within the South Polar Region of the Moon.

Following its separation from the propulsion module on August 17th, the Chandrayaan-3 lander Vikram completed a series of small adjustments to which allowed it to reduce the lowest point in its orbit to just 30km above the Moon. It was from this altitude that the lander fired all four of its landing motors to drop it into a gentle ballistic descent towards the lunar surface easing it down to an altitude of 7.2 km over a period of 11.5 minutes.

At this point the lander used its thrusters to orient itself into a vertical position in preparation for landing. Then, at 150 metres above the surface the lander held its position using two of its decent engines to hold position for around 30 seconds in order to carry out a final scan of its proposed landing area before continuing to a soft landing at 12:32 UTC.

The landing came as a source of national and international celebration – and some relief for the Indian Space Research Organisation, the mission in part being the result of the loss of the Chandrayann-2 lander / rover combination when they deviated from their planned descent to the surface of the Moon on July 22nd, 2019, striking the Moon at an estimated 50 m/s (180 km/h / 112 mph), rather than the required 2 m/s (7.4 km/h / 4.6 mph) required for a soft landing.

The entire mission operations right from launch until landing happened flawlessly, as per the timeline. I take this opportunity to thank navigation guidance and control team, propulsion team, sensors team, and all the mainframe subsystems team who have brought success to this mission. I also take the opportunity to thank the critical operations review committee for thoroughly reviewing the mission operations right from launch till this date. The target was on spot because of the review process.

– Chandrayaan-3 project director P. Veeramuthuvel

The mission has a number of objectives, with the lander and its small rover – called Pragyan (“wisdom”) – primarily focused on the probing the composition of the lunar surface and attempt to detect the presence of water ice and to examine the evolution of the Moon’s atmosphere. However, the mission is also about the rover itself and demonstrating India’s ability to build and operate a rover vehicle.

Following landing, and after surveying its surroundings, Vikram was ordered to extend a ramp ahead of the rover’s deployment. This occurred at 03:00 UTC on August 24th, 2023, when – after as series of checks, the rover was released from its locked on the lander and commanded to roll down the ramp onto the lunar surface, watched over by the lander’s cameras.

Following initial deployment, the rover paused at the foot of the ramp, before commands were passed for it to roll forward several metres and commit a turn to test its steering.

In all, both lander and rover are expected to operate for a total of 15 days within landing area – the length of time the Sun will be above the horizon in order to provide energy to the solar-powered vehicles. It is hoped that the studies the mission performs will add to our understanding of the Moon’s south pole and its role in host water ice – a resource of enormous potential and importance to future aims for the human exploration of the Moon, and being planned by the US-led Artemis programme (of which India is a member through the Artemis Accords) and China.

Yutu-2 Keeps Rocking

Meantime, on the lunar far side, China’s Yutu -2 (“Jade Rabbit”) rover continues to explore Von Kármán crater more than 4.5 years after arriving, making it the longest operational lunar rover to date, and the only rover operating on the far side of the Moon.

A part of the Chang’e-4 mission, the 6-wheeled rover is operating in conjunction with the mission’s lander, with both rover and lander having far exceeded their primary missions of 3 and 12 months respectively. For the rover, which has to contend with the harsh lunar nights, this is a remarkable achievement. During its time on the Moon it has covered a distance of around 1.5 km, exploring features within the crater and probing below the surface.

Footage of Yutu-2 captured from its initial deployment on the Moon in 2019, strung together into a movie. Credit: CNSA

The latter is achieved through the use of a two-channel ground penetrating radar (GPR) capable of “seeing” to depths of around 300-350 metres. This has revealed the Moon’s surface structure under Von Kármán crater to be remarkably complex, with at least 5 layers of rock stacked one above the last in a manner of sedimentation. However, rather than the result of water action, these appear to have been the results of volcanism, with at least three of the five layers primarily comprising basalt.

This points to the region having once been a site of significant volcanism and helps in further understanding of the Moon’s early history. In addition the different degrees to which the layers spread help inform scientists on how the decreasing thermal activity within the Moon directly correlates to the loss of volcanism and the settling of lunar features.

Following missions like Yutu-2 and Chang’e-4 isn’t easy, as the Chinese space programme is mixed in terms of the information and frequency with which it makes information publicly available. However, given the fact that this study is part of broader research into the Moon’s upper layers being carried out by the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona utilising data provided by China, demonstrates the latter’s commitment to sharing the results of their robotic space research with science institutes around the world.

Japan’s SLIM Mission to the Moon and XRISM

Japan is set to launch two important missions in the early hours of August 28th (UTC), when a H2-A medium-lift launch vehicle should lift-off from the Tanegashima Space Centre.

The primary payload for the launch is XRISM (pronounced “crism”) – the X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission, a 2.3 tonne telescope intended for a circular orbit of 550 km around Earth. It is both a successor to Japan’s Hitomi X-Ray telescope, lost in March 2016, just a month after its launch due to an attitude control system failure (and upon which XRISM is based), and as a “stop-gap” mission to take over from / support the increasingly aging Chandra X-Ray telescope (NASA) and Newton XXM telescope (ESA), and the latter’s Advanced Telescope for High Energy Astrophysics (ATHENA), due for launch in the mid-2030s.

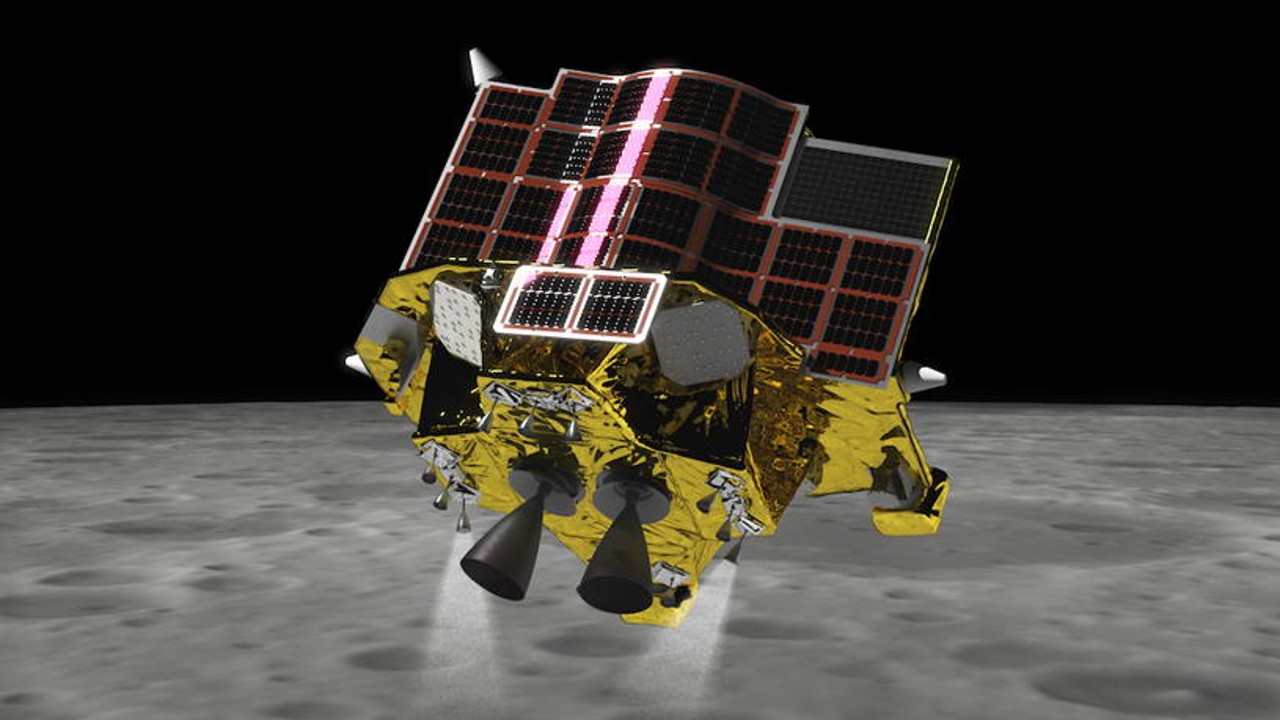

Also aboard the rocket will be SLIM – the Smart Lander for Investigating Moon.

Massing 590 kg (including its propellants), this is Japan’s first attempt to land on the Moon, and is primarily intended to be a technology demonstrator. Unlike the majority of lander missions currently underway, it will not be targeting either the far side of the Moon or the lunar South Polar Region. Instead, it will be targeting the relatively young impact crater Shioli, just 270m across, and just below the Moon’s equator.

Despite its small size, (it is roughly 1.5-2.0 metres on a side) the lander will carry both its own science instruments and two little rover vehicles. It will also use a unique method of attempting its landing: using an adaptation of facial recognition software that will allow it to recognise the craters over which it is passing in order to determine its location relative to its landing site. This – in theory – will enable the lander to place itself inside the crater.

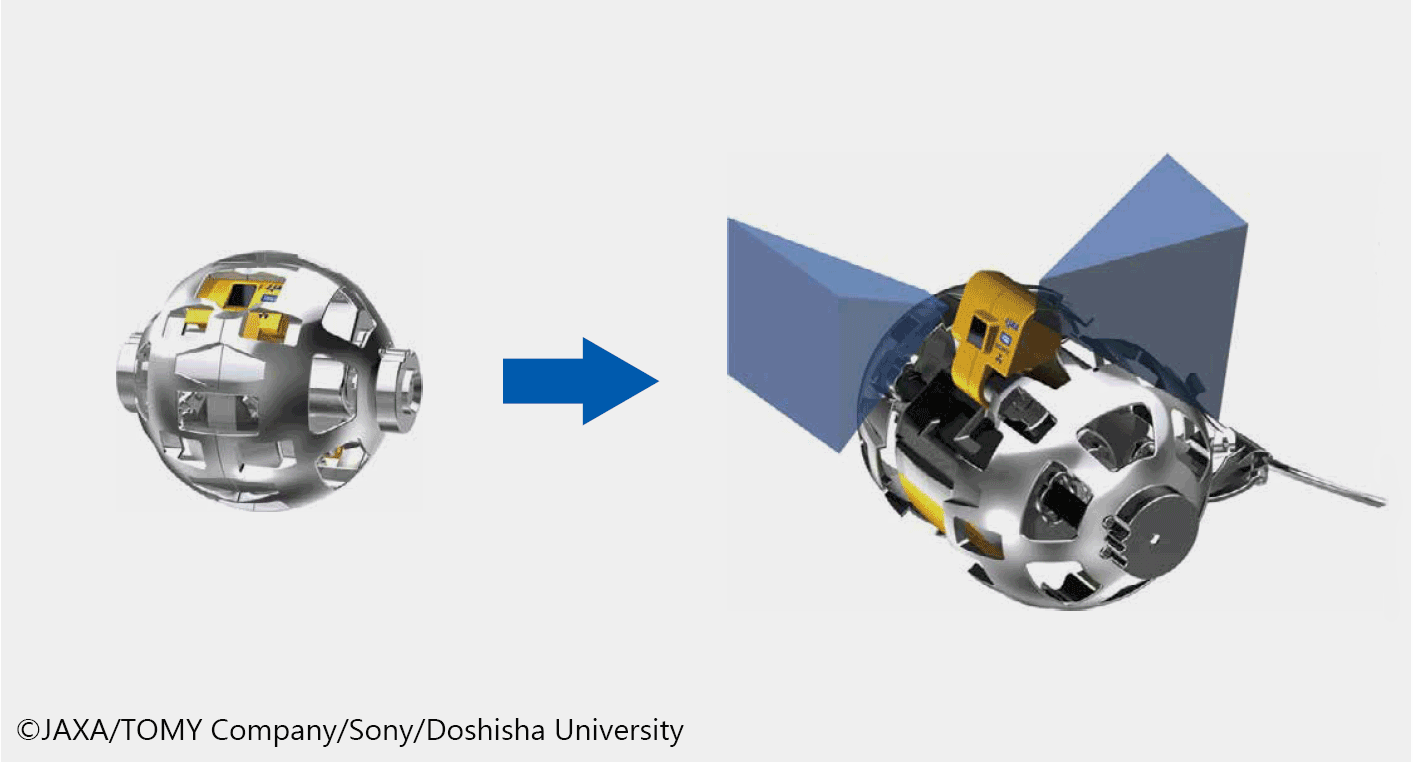

After landing, SLIM will deploy two palm-size rovers: Lunar Excursion Vehicle 1 (LEV-1) and Lunar Excursion Vehicle 2 (LEV-2).

- LEV-1 is a “hopping” rover which includes twin visible light cameras and the ability to communicate directly with Earth.

- LEV-2, meanwhile LEV-2, is a ball-shaped vehicle with a diameter of approximately 8 cm and a mass of approximately 250 g. It is designed to roll over the lunar surface and has the novel ability to alter its shape in order to do so. It is also equipped with two cameras to record its progress.

Also known as “Moon Sniper”, the mission will be making a leisurely trip to the Moon over a period of around 3-4 months. This will include multiple passages around Earth before looping out to almost 1.6 million km from Earth, before falling back into orbit around the Moon, where it will spend around a month before attempting a landing.

Launch for the missions is due at 01:26 UTC, and those who wish to witness it can do so here.

In Brief

When Putting a Hole in Things Proves a Point

ClearSpace-1 is a mission being developed by the European Space Agency (ESA) to demonstrate technologies for rendezvous with and the capture and de-orbit of end-of-life satellites.

Due for launch in 2026, ClearSpace-1 – built by a Swiss start-up also called ClearSpace – is a small satellite with four grappling arms designed to close around a target vehicle and hold it, before the satellite performs a de-orbit manoeuvre which will result in it and the captured object burning-up in the upper atmosphere.

However, there is one small – and ironic – wrinkle in the first mission for ClearSpace-1: debris got to the debris first, likely resulting in more debris.

To explain, the mission’s intended target was due to be a 112-kg payload adaptor used within the second ever launch of the European Vega rocket in 2013. Called Vespa (Vega Secondary Payload Adapter), the object may be small, but it matches the size of a load of modern satellites and occupies a typical elliptical orbit (801km x 664km).

However, On August 11th, the US 18th Space Defense Squadron – responsible for tracking space debris – reported a a number of items occupying the same orbit and in the same location as the target Vespa unit. On august 22nd, ESA confirmed it appears likely the adapter suffered a “hypervelocity impact” by another, small, piece of orbital debris.

It is not clear how much of the Vespa unit remains intact, and ESA is continuing with the development of the mission – which again, in an ironic twist, will utilise a Vega-C rocket, with ClearSpace-1 mounted on the rocket using a similar Vespa unit -, noting that it is too early to determine if the target remains viable for the mission or if another needs to be selected. But that said, this turn of events highlights the issue of having too much debris zipping around the Earth at 27,000 km/h.

C/2023 P1 Nishimura Might Be a Poor Candidate for Naked-Eye Observations – But Will be Back After All

In my previous Space Sunday update I covered the newly-discovered comet C/2023 P1 Nishimura. As is the way of these things, data continues to be gathered on the comet that helps in our better understanding of its nature.

In particular, several astronomers have cast doubt on the comet’s likely naked-eye visibility. This is in part due – as I noted – the comet’s close proximity to the Sun (being briefly either just before sunrise or just after sunset). However, it had been hoped this would be somewhat countered by the comet forming a dusty tail as it passes around the Sun, increasing its naked eye visibility. Unfortunately, more recent observations now suggest that any such tail will likely be largely gaseous in nature rather than heavy in duty and debris, and so largely invisible to the naked eye.

However, in slightly more positive news, it now appears the comet is not – as was thought – to be on a one-way trip through the inner solar system, only to be flung out of the solar system forever as a result of its slingshot around the Sun. Revised calculations on the comets mass and imparted velocity as it passes around the Sun indicate it will remain under the Sun’s gravitational influence and so will make a return to the inner solar system – in 2317. This also suggests that far from making its first passage past Earth, the comet may have made many such 294-year trips around the Sun – it’s just that we’ve never spotted it until this year.

Congrats—with a safe landing, too!

LikeLiked by 1 person