Further, group design sessions for rover driving and physical science operations normally involve teams that fluctuate in numbers – 5 to 20 or more at a time, depending on the topic of planning – that can easily congregate together for planning meetings, now must do so via video conferences, which naturally limit the more free-form nature of such discussions. This draws out the time spent in meetings – the drive team estimates they spend around 2+ hours more in daily meetings – and requires very careful follow-up and checking by team leaders. All of which limits the development and testing of code critical to rover operations.

We’re usually all in one room, sharing screens, images and data. People are talking in small groups and to each other from across the room. Now we do the same job by holding several video conferences and use messaging apps It takes extra effort to make sure everybody understands one another I probably monitor about 15 chat channels at all times and calls into as many as four separate video conferences at the same time.

– Curiosity science operations team chief Carrie Bridge

The Curiosity team began to anticipate the need to go fully remote a couple weeks before the JPL shut-down, leading them to rethink how they would operate. Headsets, monitors and other equipment were distributed to homes, and the transition has taken getting used to, but Bridge said that even so, the effort to keep Curiosity rolling is representative of the can-do spirit that attracted her to NASA.

Proof of the success came on March 20th, 2020. The MSL mission operations room at JPL was deserted, but a complex series of commands were transmitted to Mars and recorded by Curiosity. Two days later, the commands were executed by the rover, allowing it to successfully drill a rock sample at a location dubbed “Edinburgh.” It’s the first phase of a complex series of activities that will mark rover operations for the foreseeable future.

It’s classic, textbook NASA. We’re presented with a problem and we figure out how to make things work. Mars isn’t standing still for us; we’re still exploring.

– Carrie Bridge

Betelgeuse Returns to Brightness

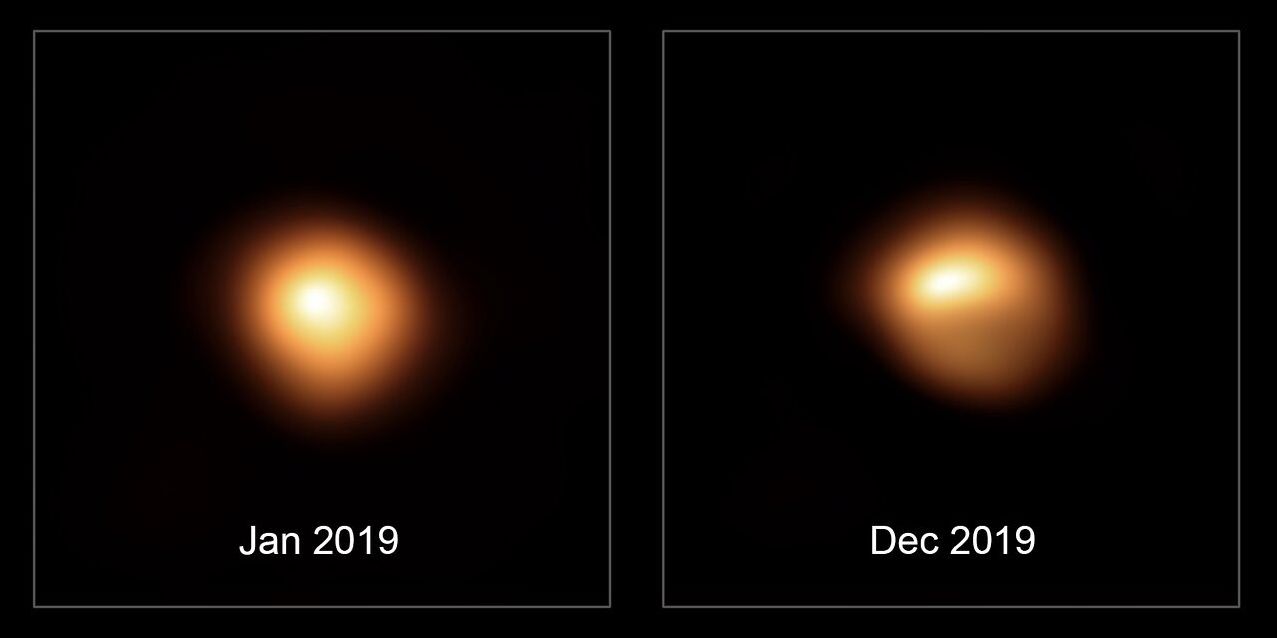

After months of speculation of what it might signify, Betelgeuse has once again almost completely returned to its full, natural brightness.

As a pulsating variable star, variations in Betelgeuse’s brightest are not unusual. However, and as I’ve previously noted in a number of Space Sunday pieces (December 2019, January 2020 and February 2020), the star’s dimming over the course of several months from mid-October 2019 through until February 2020, was particularly dramatic, dropping its apparent magnitude (brightness as seen from Earth) by a factor of 2.5 (or roughly 25-30%).

During the initial period of dimming, there was considerable speculation on social media that it could be related to the star having exploded into a supernova – its eventual fate and that we were witnessing the pre-explosion contraction and dimming, which took place some 643 years ago – that being the time it takes light from the star to reach Earth. While most astronomers believed such speculation to be in error, the degree of dimming was brought vividly into focus by images released in February 2020, which also showed apparent changes in Betelgeuse’s shape.

Astronomers attempted to point out amidst all the supernova speculation, it was likely the dimming being witnessed was likely the result of the two cycle’s in the star’s variability coinciding. The first of these cycles lasts some six years, and the second 425 days. When they coincide – which occurs roughly every 25 years – the result can be a greater than usual dimming of the star as seen from Earth; although admittedly, they haven’t in the past been quite as a dramatic as we’ve witnessed in 2019/20. As such, they were confident the star would start to brighten once more.

The latest data gathered on Betelgeuse now shows this is what has been happening. According to data gathered by the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) and published on April 17th, Betelgeuse has, over the course of the past 60 days gradually regained some 95% of its previous brilliance.

Such is the nature of Betelgeuse, it will one day supernova. Stars of its spectral class burn relatively short, bright, massive lives (Betelgeuse has an estimated diameter that extends beyond the orbit of Jupiter) lasting around 10 million years, and as Betelgeuse is thought to be at least 8.5 million years old; however, it is unlikely to occur for another 100,000 years.

OSIRIS-REx Completes Rehearsal for Sample Gathering

Launched in September 2016, NASA’s Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) is a mission to obtain a sample of at least 60 grams (2.1 oz) from 101955 Bennu, a carbonaceous near-Earth asteroid, and return said sample to Earth for a detailed analysis. It’s a mission I’ve only briefly mentioned in these pages, although the craft has been orbiting and studying the asteroid since it achieved orbit around it at the very end of December 2018.

It is currently scheduled to gather its sample in August 2020. This requires the craft to slowly close on a pre-selected location on the asteroid so that a “touch and go” sampling arm can make contact with the surface for about 5 seconds as a burst of nitrogen gas is fired. The gas is designed to dislodge dust and rock fragments, which can be caught by a sampling mechanism on the end of the arm. If required, the craft can carry out this method of sampling up to three times.

To ensure the mission is ready for the operation, on Tuesday, April 14th, a “checkpoint rehearsal,” was carried out. This allowed OSIRIS-REx to carry out the necessary gentle burn of its gas thrusters to set it drifting gently down towards the surface of the asteroid, the sampling arm fully extended. It was critical that the thruster firing was completed perfectly, as there is a risk that if the hydrazine gas reaction control system (RCS) is used when the vehicle is just above the surface of Bennu, it will contaminate any gathered sample.

As with Curiosity, planning for the operation had to be carried out with the science and engineering teams all working remotely, NASA’s Goddard Flight Centre, responsible for managing the mission having switched to staff working remotely in response to the coronavirus situation. However, the operation itself was monitored by limited teams at Goddard, Lockheed Martin (responsible for building OSIRIS-REx) and the University of Arizona (leading the science aspects of the mission).

Four sample sites on the surface of Bennu were identified in August 2019, called Nightingale, Kingfisher, Osprey, and Sandpiper. In December 2019, NASA announced Nightingale would be the primary sample gathering site, and the April 2020 rehearsal took place directly over this location. No physical contact was made with the asteroid – again to avoid possible site contamination. Instead, OSIRIS-REx was instructed to ease itself down to 65m above the asteroid’s surface which the sample area system and camera were tested, before backing away slowly again. During the actual sample gathering, the sample arm will be used to absorb the vehicle’s downward drift and use the gathered energy to effectively push OSIRIS-REx away from Bennu prior to any firing of the RCS system.

This rehearsal let us verify flight system performance during the descent, particularly the autonomous update and execution of the Checkpoint burn. Executing this monumental milestone during this time of national crisis is a testament to the professionalism and focus of our team.

– Rich Burns, OSIRIS-REx project manager

Following the August sample gathering, OSIRIS-REx will remain in orbit around Bennu until March 2021. Then it will fire its main engine to start the journey back to Earth, arriving in orbit here in 2023.

Bennu, which is approximately 492 m in diameter, is classified as a near-Earth object (NEO), meaning it occupies an orbit around the Sun that periodically crosses the orbit of Earth. Current orbital predictions have suggested it might collide with Earth towards the end of the 22nd Century. To this end, a major part of the work carried out by OSIRIS-REx has been analysing the thermal absorption and emissions of the asteroid and how they affect its orbit. This data should help scientists to more accurately calculate where and when Bennu’s orbit will intersect Earth’s, and thus determine the likelihood of any collision. In addition, the mission has been completing an orbital mapping of the asteroid and determining more about its structure and composition. Analysis of the returned sample will likely lead to a better understanding of the solar system’s early history.