Visually, it’s been a stunning week for astronomy and space science. We’ve had amazing images of the Perseids reaching this year’s peak as the Earth ploughs through the heart of the debris cloud left by comet Swift-Tuttle; there have been amazing shots of the Northern Lights Tweeted to Earth from the International Space Station; and another comet – 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko has shown us just how active a place it came become under the influence of the sun.

As I noted last Sunday, the Perseids meteor shower promised to be quite a spectacle this year, once again coinciding with a new moon which would leave the night skies particularly dark – ideal circumstances with which to see the meteor display for those able to get away from more Earthbound light pollution.

The Perseids – so-called because they appear to originate from the constellation of Perseus – are always a popular astronomical event; during the peak period, it is possible to see between 60 and 100 meteors per hour. They are the result of the Earth travelling through a cloud of dust and debris particles left by Comet 109p/Swift-Tuttle’s routine passage around the Sun once every 133 years.

As the comet last passed through the inner solar system in 1992, the debris left by the outgassing of material as it was heated by the Sun is extensive, hence the brilliance of the Perseids displays. As noted, with the peak of the Earth’s passage through the debris (which lasts about a month overall from mid-July through mid-August, so there is still time to see them) occurring at a time when there would be a new moon, 2015 promised to offer spectacular opportunities for seeing meteors – and duly delivered.

Across the northern hemisphere between August 12th and August 14th, 2015, the Perseids put on some of the most spectacular displays seen in our skies in recent years – and people were out with their cameras to capture the event.

The highest concentration of meteors was visible after 03:00 local time around the world, although by far the best position to witness the event was in the northern hemisphere, with things getting under way as the skies darkened from about 23:00 onwards in most places.

It is not uncommon for the shower to coincide with a new moon (2012, for example was the same). However, this year’s display has been particularly impressive for those fortunate enough to have clear skies overhead. “I have been outside for about 3 hours” Ruslan Merzlyako reported on August 13th. “And the results are bloody fantastic! Lots of Perseids and Northern Lights had just exploded in the sky right over my home town. For now, I am not going to argue with Danish weather, because I am 200 percent happy!”

You can find more images of this year’s Perseids event on Flickr.

Aurora From Space

Staying with the Northern Lights – more formally referred to as the Aurora Borealis – the current commander of the International Space Station, Scott Kelly, captured some stunning images of the event, some of which he shared via his Twitter feed, during the 141st day of his current mission – the joint US / Russian Year In Space – aboard the station.

“Aurora trailing a colourful veil over Earth this morning. Good morning from @spacestation!” he tweeted at the start of the series, which included a remarkable time-lapse video. With a further image, he commented, “Another pass through #Aurora. The sun is very active today, apparently.”

The Northern Lights, together with their southern hemisphere cousin, the Aurora Australis, are caused by the interaction of the solar wind – a stream of charged particles escaping the Sun – and our planet’s magnetic field and atmosphere. This tends to occur in a couple of ways.

In the first, the solar wind distorts the Earth’s magnetic field, allowing some charged particles from the Sun to enter the Earth’s atmosphere at the magnetic north and south poles. These charged particles “excite” the gases in our atmosphere in much the same as an electrical charge excites the gases in a fluorescent light tube, causing them to glow.

In the second, the solar wind actually disrupts the Earth’s magnetic field, causing field lines to “detach” from the planet, before suddenly “snapping back”. When this happens, energetic streams of charged particles are forced into the Earth’s atmosphere, again exciting the gases there and making them glow. Generally, the aurora are only visible at near-polar latitudes; however, this particular means of forming them is generally the cause when they are seen to be extending into temperate latitudes: the more magnetic field lines that disconnect and snap back, the further the aurora tend to extend across the Earth’s atmosphere.

As WordPress will not allow me to embed Commander Kelly’s original video, I’ve used the above from the BBC. Please pardon some of the drivel in the voice-over.

Rosetta Reaches Perihelion with Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko

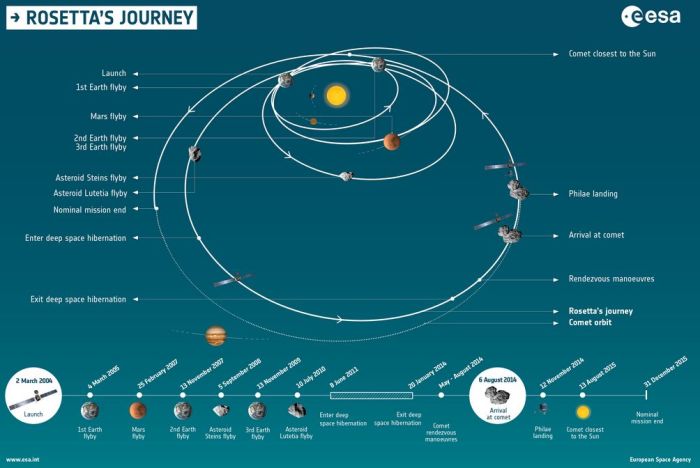

And from the solar wind, we travel to the Sun, which saw comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko reach its point of closest approach – perihelion – on August 13th, 2015. Travelling with it, the European Space Agency’s Rosetta spacecraft gathered a wealth of data as the comet reached a point some 186 million kilometres (116 million miles) from the Sun (a little greater than the Earth’s orbit around our star).

The event took place at 02:00 GMT on the morning on August 13th, just over a year since Rosetta arrived in orbit around the comet. In that time, the missions has already discovered much; however, it has been the period when the comet travels around the Sun which has always held the most promise.

Comets are among the oldest parts of the solar system, true remnants of the time when the planets were being formed. Made of up ice, dust, minerals and organic molecules, they may hold the key to how life itself began, and what may have contributed to the Earth become a stable environment in which life could take hold.

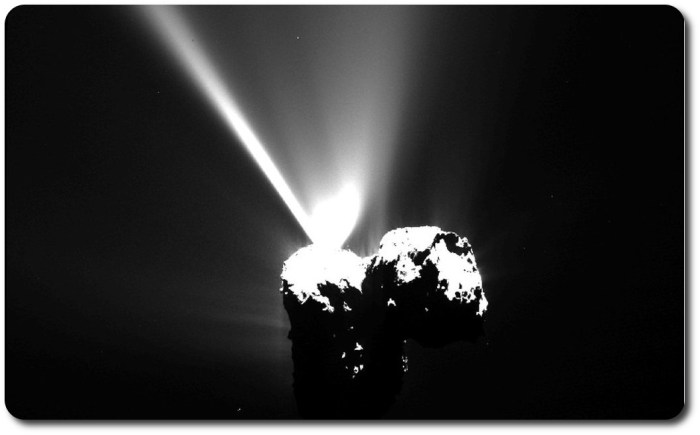

Normally this material is locked into a comet’s icy surface, but as it approaches the Sun, a comet is heated and becomes active; material is boiled, vaporised and literally “blown off” its surface to be captured by the solar wind, where it forms the distinctive tail. In the case of 67P/C-G, it is estimated that this material is being shed at the rate of 1.3 tonnes every second – around a tonne of which is dust and solid material, and the rest water vapour.

Thus, during perihelion, pristine particles left from the solar system’s birth about 4.6 billion years ago, are ejected into space – and Rosetta is there to examine and analyse them with its instruments.

“In looking at this comet — a step in that process of understanding — we are trying to understand why our system turned out the way it did, why Earth had stable water, and the ingredients that led to what we are today, that is a planet of living beings,” astrophysicist Jean-Pierre Bibring of the Institute of Space Astrophysics, commented during perihelion.

The comet will remain active for many weeks as it starts on its slow “climb” away from the Sun, heading back to aphelion – the point furthest from the Sun. It’ll reach that point in a little over 3 years, beyond the orbit of Jupiter, and then start back inwards once more, its overall period – the time it takes to complete a single journey around the Sun – being around 6.5 years.

Rosetta will continue to observe the comet as it heads outwards once more, gathering more data and images as it does so, the mission slated for a nominal end in late December 2015 – although if the vehicle is still functioning, it could well be extended.

Sadly, while this phase of the mission has been a success, the exact status of the Philae lander remains unknown; there has been no further contact with it since the June / July attempts, and Rosetta has since moved away from the comet to avoid the risk of damage from any material being ejected, making communications even harder that was already the case given Philae’s main communications system already appeared to be broken.

Theoretically, the sunlight striking the comet should be sufficient through until October to maintain Philae’s battery levels, so those involved in the project remain hopeful contact may be re-established when Rosetta moves back closer once more – although again, that is assuming the lander isn’t cooked by the high temperatures of perihelion or suffers other damage as a result of the comet being so active. But, the little lander has already shown itself to be remarkably robust, so there is hope the data it gathered during the first part of its mission may yet be fully recovered.